What’s hiding behind many low-fat food claims

It was a routine medical procedure that first brought us together, and for me, it was love at first bite. Lemon-flavored Luigi’s Real Italian Ice was on my mostly desultory list of foods approved for colonoscopy prep. It was only 100 calories and tasted divine — sweet, with a sort-of grainy texture.

Before long, Luigi and I had a regular thing going, two or three nights a week. I didn’t bother to read the nutrition facts, but why would I? I already knew it was fat free. It said so on the front of the box, in bright yellow, block capital letters.

When I finally looked at the nutrition facts, I didn’t like what I saw. Each cup contained 20 grams of sugars, the equivalent of five teaspoons. In exchange for zero fat content, I was getting 80 calories of sugar (at 4 calories per gram).

If you figure that I can eat 200 calories of sugars each day (the new U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommend I get no more than 10 percent of my total calories from sugars), then I was using 40 percent of my daily allotment on one little treat.

That was the trade-off: no fat but lots of sugar — more than three-quarters what I would get in an 8-ounce bottle of regular Coca-Cola, the type of thing I normally eschew for being too sugary.

That’s the way it is with fat-related claims on packages on everything from salad dressings and yogurts to cookies and frozen waffles. The front of the package shouts “fat free!” but the truth is elusive.

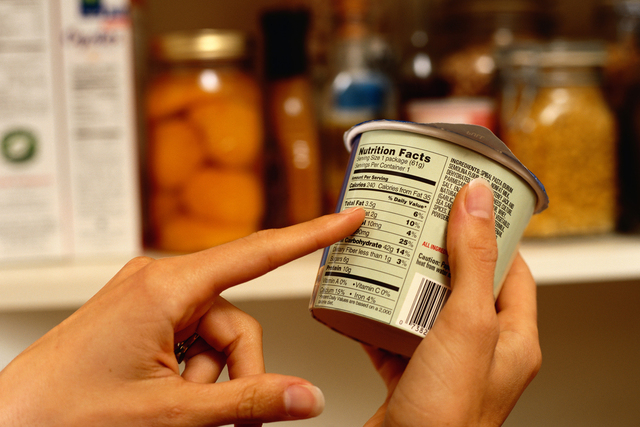

To start finding the truth, said Miriam Een, assistant professor of nutrition at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, you have to summon your inner nutrition wonk. Flip the package on its side and take a close look at the nutrition facts. That’s where the good stuff is.

It’s not that the claims on the front of the box are untrue, exactly. The Food and Drug Administration regulates such claims, so they’re (mostly) true, as far as they go. But they only go so far.

“I would say they’re quite misleading,” said Alison Paulson, clinical dietitian at University Medical Center.

“Many people these days are really worried about calories, so they’re looking for lower fat options,” Paulson said. “The food companies have kind of capitalized on that, and started to label a lot of their food fat free, low fat and reduced fat.

“But the problem is, this food still has a delicious taste, and where does that come from? It comes from adding things like sugar.”

In addition to sugar, processed foods that have been stripped of fat may be loaded with salt and other additives to restore flavor and texture. The calories can add up.

“People assume that if it is fat free, then I can have more of it, or that fat free means calorie free, and that’s just not the case,” said Sherry Poinier, a dietitian at Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican in Las Vegas.

In fact, “fat free” doesn’t necessarily mean “fat free.” Under the FDA’s rounding rules, foods that are labeled “fat free” or that claim 0 grams of trans fats may contain 0.5 gram of fat, or trans fat, per serving.

Otherwise, the rules regarding fat claims are pretty straightforward: A food labeled “low fat” can’t have more than 3 grams of fat per serving. A “reduced-fat” food must have at least 25 percent less fat than the regular version. “Light” foods must have either 50 percent less fat or one-third fewer calories than their regular counterparts.

The thinking surrounding dietary fat has undergone a sea change since the 1990s, when the prevailing wisdom held that a low-fat diet was key to weight loss and long-term health.

But the evidence just wasn’t there, according to a report from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. These days, “it is the type of fat, not the amount, that is most important,” the report stated.

There are several types of fat and understanding which is which will serve you well over a lifetime.

The good-guy fats are unsaturated (either monounsaturated or polyunsaturated). These fats lower disease risk and do not raise cholesterol. They’re found in things such as vegetable oils, most nuts, olives, avocados and fatty fish like salmon. Unsaturated fats can be high in calories, so moderation is key.

Saturated fats, found in dairy products like cheese, whole milk, butter and ice cream, are bad fats because they tend to raise blood cholesterol. Dietary cholesterol itself is a type of fat that raises blood cholesterol, and is found in liver and other organ meats, egg yolks and dairy fats.

Also bad are trans fats, which are the ones made by adding hydrogen to liquid vegetable oils. Food makers use trans fats for texture, shelf life and flavor. But trans fats contribute to the buildup of plaque inside the arteries that may cause a heart attack. Fortunately, many food makers have cut back or stopped using trans fats. The FDA is trying to get them out of food entirely.

“The type of fat matters,” said Damon McCune, a dietitian and director of the Didactic Program in Nutrition and Dietetics at UNLV. “For the most part, we recommend less than 10 percent of total daily calories from saturated fat. If you have a 2,000-calorie-a-day diet, 10 percent would be 200 calories. There’s nine calories per gram of fat, so you would divide the 200 by nine to give you the amount in grams.”

While it may be a good thing that food makers are offering reduced-fat alternatives on store shelves, the sugar and salt that are added to compensate for lost flavor “are actually more concerning,” especially for people with diabetes, Paulson said.

And calorie-wise, consuming a reduced-fat product versus the regular version can be a draw, or pretty close to it.

“Even though something is quote-unquote low fat, it may have the exact same number of calories because they may have replaced the fat with carbohydrates or something else to maintain consistency and flavor,” McCune said.

Een finds the Oreo cookies example instructive. A serving of three, Reduced Fat Oreo cookies has 150 calories, just 10 fewer than three, regular Oreo cookies. Sure, you save 1 gram of saturated fat, but is it worth it?

“Personally, I like the regular Oreos better,” Een said.

The law of unintended consequences may come into play here as well: Say a fat-free or reduced-fat claim on a package catches our eye at the grocery store. We drop the product into our cart thinking we’re doing ourselves some good. But at home, we eat more than we would have otherwise.

Another problem is that food makers sometimes don’t make it easy to make apple-to-apple comparisons between reduced-fat foods and their regular counterparts.

Take Reduced Fat Wheat Thins. A serving size is 29 grams, or 16 pieces, for 130 calories, and 0.5 gram of saturated fat. The serving size for regular Wheat Thins is the same number of crackers but 31 grams, for 140 calories and 1 gram of saturated fat.

Doing the math on that one makes my eyebrows hurt.

McCune has another idea. Apart from low-fat milk (which is good because all the saturated fats are removed but the healthy nutrients are left in), he neither encourages nor discourages his patients from eating foods that make low-fat claims.

What he recommends is portion control and looking at the big picture of what foods you put into your body each day. If you want ice cream at night, then go for it. But make up for it by trimming saturated fats earlier in the day. It’s all about striking a balance, McCune said.

You can also follow Een’s advice and stick mainly with the original low-fat foods. Those would be fruits and vegetables.