Occupational therapy students’ devices help the disabled

It’s a yoga mat for people with arthritis!

But wait! There’s more!

It’s a device that allows gun owners who have had an arm amputated to load and cock a pistol! It’s finger weights to help strength-impaired musicians fret a guitar or ukulele! It’s a magnetic diaper-changing bed that allows a parent who has lost movement of an arm to a stroke to change a baby’s diaper!

Each rivals in ingenuity anything you’ll ever see being pitched on a TV infomercial, and every one of them was created by students of Touro University Nevada’s School of Occupational Therapy.

These examples of assistive technology and a few dozen others were unveiled recently during the school’s Assistive Technology Fair, where students demonstrated products they created or adapted to help people with disabilities perform everyday tasks.

Yvonne Randall, director of Touro University Nevada’s School of Occupational Therapy, says the project, which arrives at roughly the midpoint of the school’s master’s degree curriculum, often inspires dread among students.

“I’m the director of occupational therapy, and this is my class, and this is their final project,” Randall says. “And they freak out: ‘Oh, my God, I’ve got to make something!’ ”

However, Randall always is pleased — and was so again this year — by the students’ creativity and the real-life utility of the devices they’ve adapted.

“The goal of our profession is to help people re-engage in their lives,” she explains, and this year’s crop of devices was designed to help people cook and dine, care for children, don or doff clothing, put on makeup, move around more comfortably and even pursue hobbies and passions.

Two students, for example, created devices that will help gun enthusiasts hold and fire pistols, rifles and shotguns. Both students, Randall says, “were, ‘I don’t know. Dr. Randall is not going to like this.’ But why wouldn’t I like it, if that’s part of someone’s life?”

Randall says she often recommends that stumped students try to imagine what they might no longer be able to do if they were to suffer a stroke or paralysis or a medical condition that hampered their own mobility or dexterity.

“What do you really love to do? What are you passionate about? Is it photography? Is it cooking?” she says. “Now, imagine that you had a stroke. What would change in that activity for you, and how could you go about resuming it?”

In some cases, the assistive devices the students created or adapted were inspired by the needs of clients they met while doing required field work. In others, students were inspired by challenges faced by members of their own families.

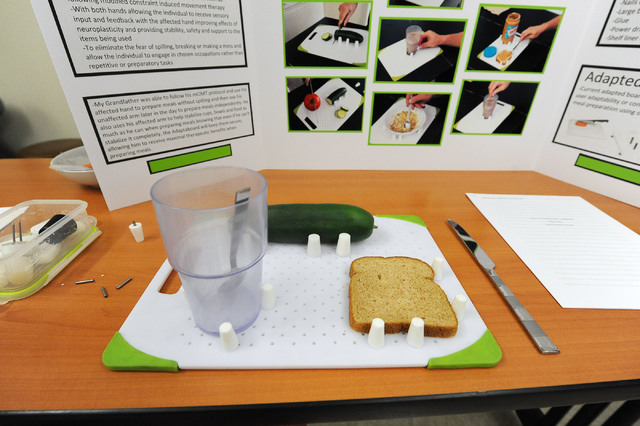

For instance, Johnny Rider was inspired by his grandfather when creating the “Adaptaboard, A One-Handed Solution to Meal Preparation.” The pegboard-and-peg system allows foods, plates, cups and bowls to be anchored down by people who can use only one hand to prepare and eat meals. The thimblelike anchoring pegs can be moved around on the pegboard to anchor a plate, a vegetable or fruit for cutting, a slice of bread for spreading or a cup for filling by using just one hand.

“My grandpa had a stroke earlier this year,” explains Rider, who came up with his design while watching his grandfather do finger dexterity exercises.

His grandfather even was able to take Adaptaboard out for a spin and, Rider says, “he was able to prepare his breakfast without waking up his wife.”

The project came in well below the $60 cost limit, too.

“The pegs cost a total of 75 cents, but if you buy in bulk they’re way cheaper,” says Rider, who’s already thinking of seeking a patent on the device.

Kerielle Williams’ 4-year-old daughter, Jaidyn, has a congenital condition that limits the mobility of her left arm and shoulder. For her project, Williams created a strap-and-brace system that — as a smiling Jaidyn demonstrates in photos posted at Williams’ display — “supports her hand and allows her to pick up food,” Williams says.

Many of the assistive devices students created allow people to perform daily tasks. Sylvia Niemyjski, for example, created a “Low-Vision Spice Rack” that incorporates a magnifying panel to help those with impaired vision read spice bottle labels.

Dani Goddard’s assistive technology device was inspired by a woman in her 30s who, after a stroke, could not use her right hand to diaper her child. Now, by using clips attached to magnets and positioned on a metal changing table, the woman can anchor a diaper for easy one-handed fastening.

“I used to be a nanny. I’ve changed a lot of diapers, ” Goddard says. “And there are very few adaptive devices for parents.”

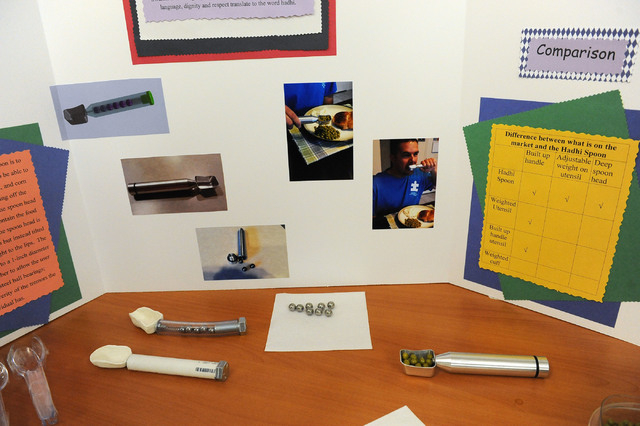

Chris Gutierrez created what she calls the “Hadhi Happy Spoon,” an oversized, weighted spoon inspired by a client who, because of tremors caused by Parkinson’s disease, was unable to eat peas or other vegetables with a conventional utensil.

Gutierrez says the goal was to restore dignity to people who have tremor-related conditions. But, she says, “I couldn’t call it the Dignity Spoon, because that sounds strange. So I went online and found that in Swahili … ‘hadhi’ means ‘respect.’ ”

Lauren Hoppe was inspired by her cousin, Aden, 4, who has a bone condition that has required him to spend long periods immobilized in leg casts. Her device, a wheeled platform that she calls the “Scoot Around,” allows Aden to lie on his stomach and propel himself with his arms.

“He loves it,” she says. “He was mad I took it away from him to bring it here.”

Students also found ways for clients to pursue their favorite hobbies and recreational activities.

Hayley Meredith, for instance, notes that rolling and unrolling a yoga mat can be painful and difficult for people with osteoarthritis. So, she created a “Roll and Wrap Yoga Mat” that incorporates a window shade mechanism with a yoga mat. The yoga enthusiast unrolls it by standing on the edge of the mat and pulling, and rolls the mat back up by working the shade mechanism.

Gary Pearson adapted an Xbox game controller for a 35-year-old client who lost dexterity in his hands because of a brain injury.

“The idea is to make it more workable,” Pearson says, demonstrating, through extension of the triggers, building up the buttons to make them easier to press and making the controller easier to grasp.

“I asked him what he wanted to do but couldn’t anymore, ” Pearson says. “And he said, play with his kids.”

Nicole Dickson’s “Grip-Free Glove and Rack” allows her client, a man whose osteoarthritis makes it difficult to grab a dumbbell, to fasten a strap on a modified gym glove to secure a dumbbell. Then, to take the glove off, the man can use a hook attached to a rack that easily pulls away the Velcro strap.

She designed the system for 10-pound dumbbells.

“I could have tried more, but he has osteoarthritis and he hasn’t been able to work out for years,” Dickson explains. “He’s lost his strength. So 5 pounds is kind of where he’s at.”

Tiffany Poon’s “Store-Away Corner Chair” was designed for a child who has cerebral palsy. With the straps affixed to the back of the lightweight, collapsible wood chair, the child can sit on the floor with other children at school without needing an adult’s support.

Brett Bonetti’s “Grip N Gun” and “Hunt N Holster” systems use Velcro patches affixed to a shooting glove and also to a shotgun or other firearm to allow easier grasping of the weapon, and holsters that are easy to use for shooters with dexterity or strength issues. Similarly, Austin Lepper’s “Handgun Helper” uses a clamp-and-stirrup mechanism to allow someone who has had an amputation or who can’t use an arm because of a stroke or other condition to load and cock a pistol one-handed.

For musicians, Ryan Hua created the “Weighted Finger Buddy,” a series of 1-ounce fishing weights attached to small loops that, worn on the fingers, provide added weight for pressing a guitar’s or ukulele’s strings against its frets.

The oddest thing about the devices on display was that, without having a reason to do so, most people wouldn’t imagine that the devices would even be necessary. But, after seeing them, the surprising thing is that nobody has thought of them before or has found a way to build them so inexpensively.

Some students say they’re considering seeking patents for their creations. In fact, don’t be surprised if you even see a few of them in discount or sporting goods store a decade or two hence.

Randall notes that products that begin their lives as assistive technology devices sometimes do filter into the general marketplace. Take, for instance, the ubiquitous no-spill adult travel mug/sippy cup.

Twenty years ago, the adaptive market “was where you got that,” Randall says. “Now, we’re walking around with our Starbucks sippy cups all the time.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.