Calendar convergence puts Easter on same day for Western, Eastern Orthodox Christians

Christmas is easy. December 25th. This year. Last year. Every year.

But Easter? Not so much. The date on which Easter falls changes from year to year, not only for Christians who observe it as a religious holiday but for secular celebrators, too.

And to make things even more confusing: Orthodox Christians often celebrate Easter on a totally different day than their Western-churched brethren. Except when they don’t. This year, for instance.

Today, Orthodox Christians will join non-Orthodox Christians — Roman Catholics, Anglicans and Episcopalians, Lutherans and other Protestants, most nondenominational and interdenominational Christian churches — in celebrating Easter, the day on which Christians believe Jesus rose from the dead, on the same day, in a confluence of dates that occurs once every few years.

Why do Orthodox Christians and non-Orthodox Christians usually celebrate Easter on different dates? It all comes down to the differences between the Julian calendar that Orthodox Christians use to determine the date of Easter and the Gregorian calendar — that’s the calendar used today in most of the global secular world — used by Western Christian churches.

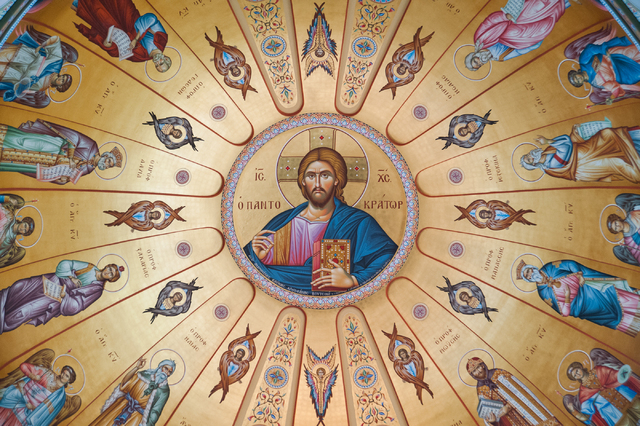

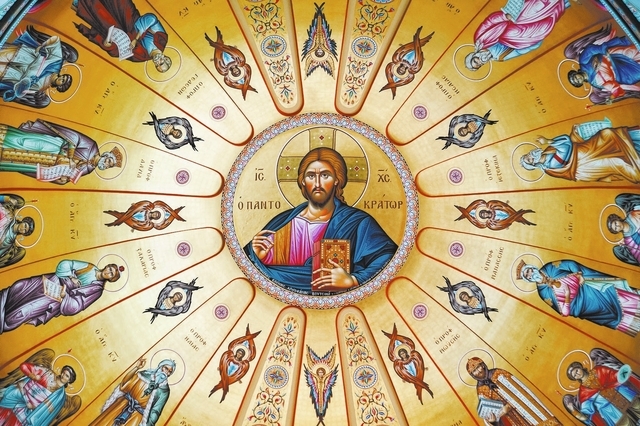

Determining the proper date for Easter is no insignificant thing, given that Jesus’ resurrection is the foundational event of Christianity. In fact, notes the Rev. Matthew Swehla of St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church, 5300 El Camino Road, establishing a date for Easter was “one of the most important issues” early Christian bishops gathered to discuss at the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325.

“Some churches were celebrating Easter weekly, some monthly and some on different dates,” Swehla explains.

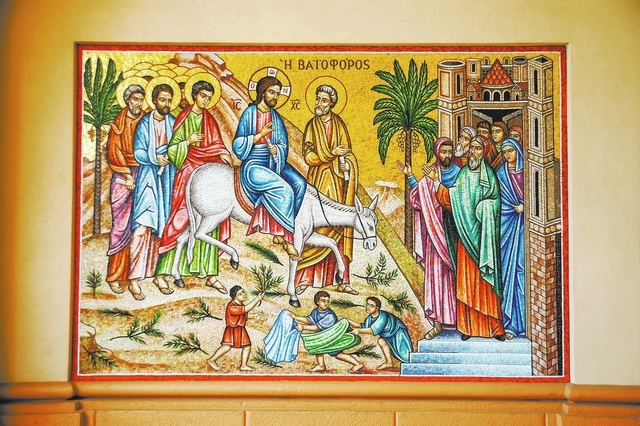

The council’s decision: Easter would be on the first Sunday after Passover, after the first full moon, after the vernal equinox (when daytime and nighttime are of roughly equal duration).

Then, a few hundred years later, Eastern and Western Christian churches divided in what now is known as the Great Schism of 1054. While the authority of the bishop of Rome was a significant factor in the split, Swehla notes that the Schism was the culmination of various theological disagreements that had arisen over previous centuries.

Since then, all Orthodox churches have continued to use the Julian calendar to determine the date of Easter, while Western churches came to adopt the Gregorian calendar, devised by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and which was, itself, an attempt to further refine the calculation of when Easter is to occur.

As a result, in most years, Easter falls later for Orthodox Christians than it does for non-Orthodox Christians. Usually, the difference is about a week, Swehla notes, although Orthodox Easter also can fall as much as a month or so after Western Easter.

However, the Julian and Gregorian calendars do mesh every two to five years and Orthodox and Western Christians end up sharing a common date for Easter. In fact, Swehla says, while most Orthodox churches have adopted the Gregorian calendar to determine the dates of other observances — those churches even celebrate Christmas on Dec. 25 each year — all Orthodox churches continue to use the Julian calendar to determine the date of Easter or, as it’s known in the Orthodox tradition, Pascha.

Like Western Christian churches, Orthodox Christians prepare for Easter with Lent, a traditional 40-day period of penance, fasting and almsgiving. In Orthodox churches, Lent begins with “Clean Monday,” and while Catholics receive ashes on their foreheads to mark the start of Lent, “there’s no anointing on the forehead, as in some traditions,” says subdeacon Jon Failla of All Saints Russian Orthodox Church, 11 N. Mojave Road.

Orthodox Christians fast on each day of Lent, abstaining from meat, dairy products, wine and olive oil. While the particulars may vary from tradition to tradition, Deacon Ozren Todorovic of St. Simeon Serbian Orthodox Church, 3950 S. Jones Blvd., notes that Orthodox Christians generally consume nothing that comes from an animal, including meat, eggs or milk.

The purpose of Lenten fasting is “to bring the body in commission with the spirit,” Failla says. “So we deny ourselves the temporal, material comforts of this earth to make ourselves more aware of the spiritual benefits that exist that are more sublime.”

During Holy Week, “there are services every day, and there’s an even greater push toward more fasting and preparation,” Failla says.

Holy Thursday brings the reading of Gospel passages that recount the story of Jesus and leading to the crucifixion, Failla says. Holy Friday services are “extremely solemn,” he says, and include Scripture readings and prayers “that foreshadow the Resurrection. Even though they talk about the suffering and Passion and loss of paradise by man, even by the evening of Friday night there are glimpses and hints in these prayers of the service that point to what’s to occur on the day of the Resurrection.”

Holy Saturday is spent in prayer, Failla says. Then, late at night on Saturday, Orthodox Christians gather for prayer before the start of Pascha liturgy at midnight.

Swehla says that, in the Orthodox tradition, prayers, Scripture readings and hymns don’t simply retell the story of Jesus or “re-create the past.” Rather, he says, “we are, in a mystical way, participating in Christ’s betrayal, his crucifixion, his death and his ultimate resurrection.

Pascha liturgy typically ends in the early morning hours. Immediately afterward or later on Pascha, Orthodox parishioners may gather for a dinner featuring foods brought to the church for blessing and shared with one another, Failla says. Because Orthodox churches encompass many regions and cultures, Pascha celebrations probably will incorporate each congregation’s foods, traditions and cultures.

“Each ethnic Orthodox church brings something unique,” Failla says.

Swehla says Orthodox Christians also receive red dyed eggs at Pascha as a symbol of Jesus’ resurrection. Then, as someone cracks his or her egg with the egg of another person, the greeting of “Christ is risen” is answered with the reply, “Truly he is risen.” Swehla adds that the verb tense (the use of “is”) underscores Orthodox belief that the events of the Passion are “mystically occurring today.”

Todorovic says that in the Serbian Orthodox tradition, the Pascha celebration typically includes the roasting of a lamb, and the “nicest decorated egg we’ll leave in the house for the year.”

A benefit of having both Orthodox and Western Easter on the same day is that Orthodox Christians may more easily participate in Easter gatherings with non-Orthodox family members.

“In a lot of families, not all are Orthodox,” Failla says. “Sometimes we are fasting (on non-Orthodox Easter), and that makes it kind of awkward. We can’t go to Easter dinner at Grandma’s, or we can, but we’re kind of like Debbie Downer because we’re fasting.”

Because of marriages between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Christians, “that does happen a decent amount,” Swehla says, and most families simply choose to celebrate both.

But, he adds, “for our parish, I haven’t seen a lot of conflict or turmoil.”

Conversely, Todorovic says observing a later Easter makes it easier for Orthodox Christians to get time off from work to celebrate Pascha, a concern that’s particularly acute for Orthodox Christians who work in the tourism and service industries here.

Failla jokes, too, that when Pascha follows Western Easter, Orthodox Christians “get all the great deals on Easter baskets. Because (Easter is) over for them, on Monday morning we buy them all.”

More seriously, Failla says celebrating on the same day is “wonderful, because not only can I share the joy of the Resurrection with my entire family and my wife’s entire family, but for me it foreshadows what I believe in and pray for on a daily basis, which is the unity of all Christians. So when we have time to celebrate the holiest day of the year as one community in Christ, with Christian people throughout the world, it’s tremendous.

“I have to say that when all of us celebrate the Resurrection at the same time, that it’s certainly more glorious because the energy of prayer is magnified by the number of people participating in the celebration of that glorious event that, really, was the catalyst of our whole faith.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280