UNR professor wants readers to gain appreciation for Great Basin

Think: Cagney amid the cacti. Then utter the phrase — “Why, you desert rat!” — referencing a label this man wears proudly.

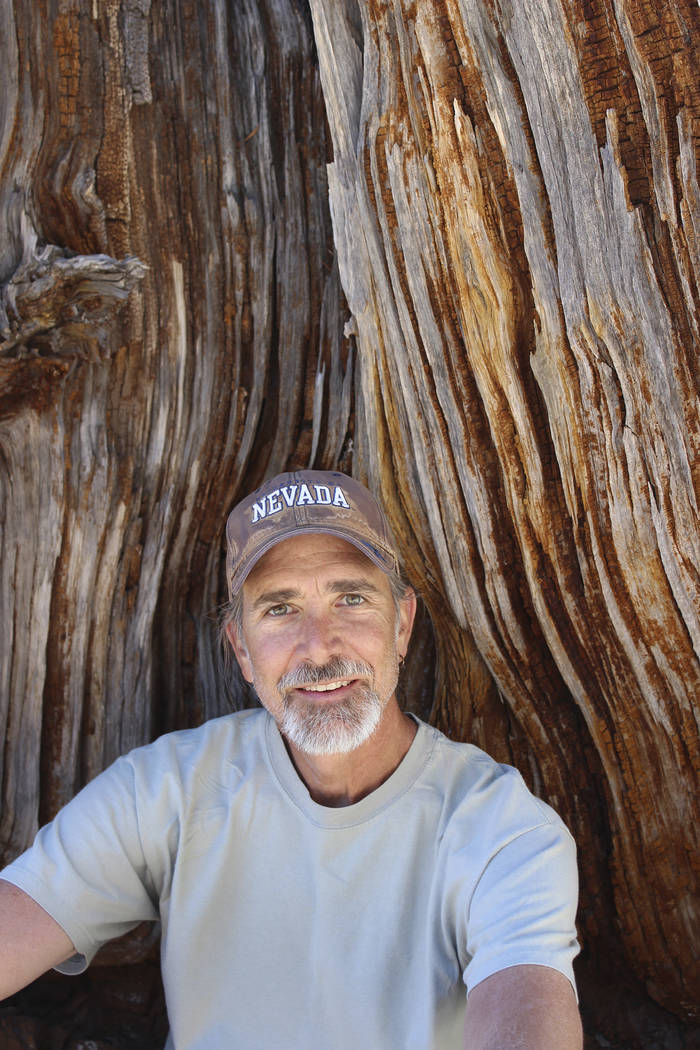

“I consider that an honorific!” says Michael P. Branch with a hearty guffaw. “It’s a way of saying this place is so far under my skin. You think of a rat as burrowed down, in there for the long haul. That’s how we feel too. This is our place.”

Find proof on every page of Branch’s verbosely-but-humorously titled book, “Rants From the Hill: On Packrats, Bobcats, Wildfires, Curmudgeons, A Drunken Mary Kay Lady & Other Encounters With the Wild in the High Desert.” Released in June, the book by the University of Nevada, Reno, professor of literature and environment, is a laugh-out-loud journey through his life in Nevada’s Great Basin Desert with his wife and two daughters.

Sober environmental discourse is fine, but consult “Rants” for cheeky tales ranging from bees hiving in the walls of his house and an owl trying to eat his daughter’s cat, to a bird dog with “toxic” flatulence and the desert discovery of a pile of “well-preserved, Nixon-era Playboy magazines.” Underlining it all is Branch’s unabashed love for desert living.

Review-Journal: Why did you deploy humor in a book focusing on the environment?

Branch: One of the biggest mistakes we’ve made is this reputation environmentalists have for being judgmental, sanctimonious and condescending. Humor bonds people and makes them less defensive. We need to try techniques other than just telling folks they’re wrong.

Are there misconceptions about the beauty that exists in the desert?

It has a lot to do with the European landscape aesthetics we inherited. We were taught to see snowcapped mountains and lakes and fields of wildflowers as beautiful. Going all the way back to ancient texts, the desert has always been used as a shorthand for a place that is uncivilized and dangerous and exposed, where rules don’t apply. In the Old Testament, when the word ‘desert’ is used, it’s often not referring to a particular geography but to a place that is absent of Christian values, a place that’s a moral vacuum, where the rules of civilization somehow don’t apply.

As a writer, how do you reverse those perceptual biases?

Without saying it directly, I’m assuming a reader who doesn’t understand or appreciate the Great Basin, and I’m sort of trying to trick them into becoming a little more educated about it by telling stories about this place, rather than preaching at them. We’re a certain kind of mammal, we like to be near water and cover and green stuff and things to eat, and the Great Basin lacks a lot of that so getting used to seeing something that’s big and empty and beautiful is really important but hard to come by. I’m trying in my own small way to show people a desert they’re not familiar with.

Is cultivating a leisurely appreciation for nature more difficult in today’s society?

We’ve become a culture that is very fast-moving and distracted, and our relationships to natural places need to get cultivated through attentiveness. You can walk through this place and tell people there’s nothing there. Yet if you walk through the Great Basin with somebody who knows what to look for and how to look for it, I can show you packrat nests and scorpions, and pick up snakes. It takes a long time to build intimacy with the landscape. Part of what I’m hoping the book can do for folks is help them slow down enough to practice the art of observation.

Does desert living ever leave you feeling disconnected from the rest of society?

Part of the issue is solitude. A hundred years ago, Americans spent more time by themselves when they did their work or maybe lived in communities that weren’t quite as dense. We’re so connected now in so many ways that just being by yourself is something that may be a little more difficult for some people. But there is compensation in that balance. I don’t feel disconnected from people as much as I feel reconnected with something more than just people.

How has desert living affected your daughters?

When the girls were little, being part of this world was really important to them. Seeing a bobcat or going outside in the evening to look at an owl hooting on our roof, those things were very enriching to them. I don’t think they went into their social relationships with any disconnection. They’ve been very well-adjusted. It’s given them the ballast of knowing there is this really beautiful, interesting world beyond those social friends that will always be here for them.

Are there ever times when this lifestyle becomes onerous?

Living up here can be a serious pain in the (rear). Logistically, it’s inconvenient in all sorts of ways. There are days when I think, yeah, it’s beautiful but what I’d give to have a place in town right now. But when you have contact with the natural world, and you’re a part of that world, you’re subject to its forces and influence. When I’m out on the land here, I have to play by these rules if I want to be safe. I’m just another organism on the land, and I really like that connection. When other things are difficult in life, this feels like you still have your feet under you and you know where you are, and that’s been really meaningful.

Contact Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@reviewjournal.com. Follow @sborn1 on Twitter.