CampMed in Las Vegas offers teens close-up view of medicine

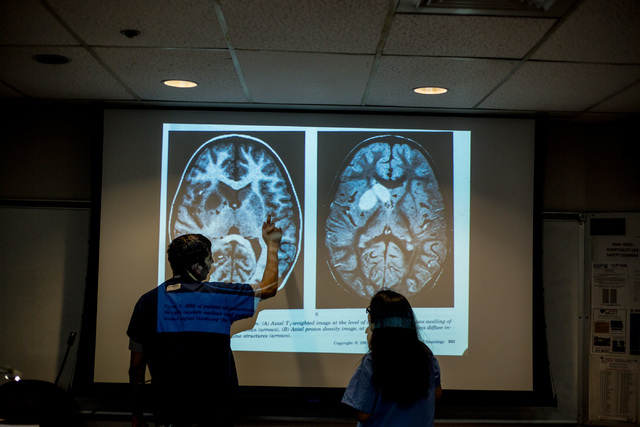

Kalyan Tatineny, a radiologist with Radiology Associates of Nevada, projected two chest X-rays side by side on screen in the University of Nevada, Las Vegas classroom. One showed an internal image of a typical, healthy body — each translucent rib in alignment, a clearly defined, asymmetric heart and nearly invisible lungs. The image on the right was atypical, showing an enlarged heart with less clearly defined borders.

“So if it’s cloudy, it’s fluid?” Khaya Tawatao, a 14-year-old aspiring orthopedic surgeon, asked, pointing to the hazy areas around the heart in the right image.

“Yeah, fluid,” Tatineny said, nodding.

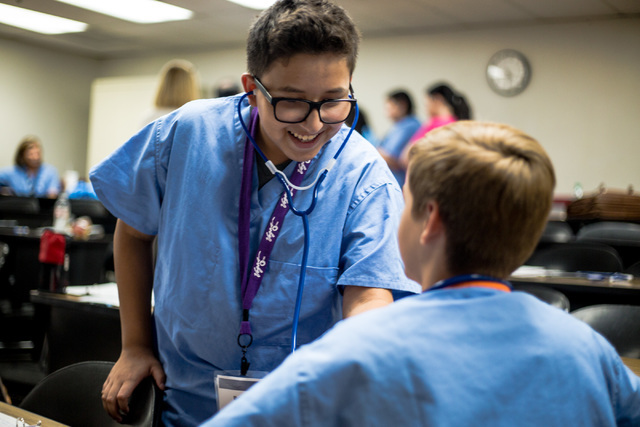

The future doctor, in light blue scrubs, and her more experienced counterpart in dark blue worked through a patient’s scans at CampMed, a two-night, three-day program for rising ninth-graders interested in pursuing a career in the medical field. Through the work of staff from Roseman University of Health Sciences, Touro University Nevada, UNLV School of Medicine, Clark County Medical Society, University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine and community physicians and medical experts from Las Vegas, nearly 50 participants from across the Las Vegas Valley learned the ins and outs of a health career and solved a case as if they were actual medical students from July 21-23.

The chest shown in the unhealthy image belongs to the fictional 9-year-old patient Steven Trepost, whose condition the CampMed participants worked to diagnosis over the course of the camp. The first day, participants learned why some of the physician volunteers entered the field and played team-building games.

At the end of the day, they were introduced to Trepost’s symptoms: His condition began with a sporadic fever and sore throat, then progressed to swollen, painful joints, shortness of breath, a rash and uncontrollable twitches and “dancelike” movements.

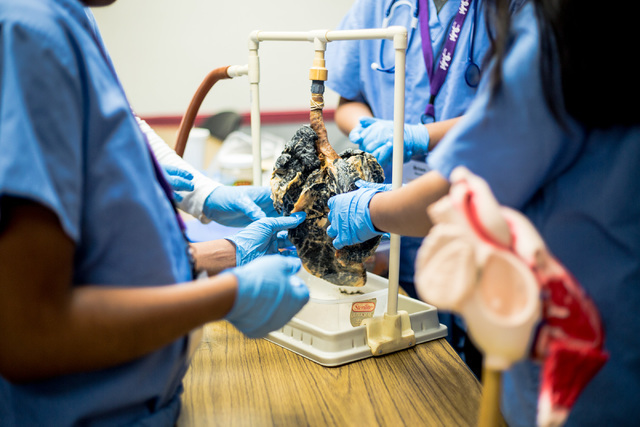

The second day, CampMed participants rotated through a series of labs that analyzed Trepost’s condition from the point of view of family medicine, infectious diseases, cardiology, radiology and neurology. The participants were divided into five groups; each group rotated through every lab, but presented from the perspective of one medical specialty on the final morning.

In the radiology lab, Tatineny walked Tawatao and the rest of her group through reading an X-ray: which areas should be dark, which should be light (lightness indicates higher density; when an area that should be dark is light, it can indicate fluid build-up, as in Trepost’s chest) and what a normal-sized diaphragm looks like.

“You can’t get enough of it, you’re always wanting more, especially if you’re given a case, you’re like, ‘I need to figure this out, I want to get it right,’” Tawatao said during a break between sessions.

Talece Flaack-Sanchez, 14, echoed that sentiment — she wanted more. “I knew it would be fun, but I didn’t think it’d be this fun. I just kind of wish it was a little bit longer.”

This was CampMed’s first year in Las Vegas. Ken Rosenthal, the director of microbiology and immunology at the Roseman University of Health Sciences College of Medicine, founded a nearly-identical camp in Ohio during his time at Northeast Ohio Medical University. When Desert Meadows Area Health Education Center proposed a summer program for teens interested in the medical field, Rosenthal knew exactly how to replicate the Ohio’s MedCamp in Las Vegas.

Through the camp, the partnering institutions hope to foster in the students much more than a casual, passing interest in the medical field and lay the foundation for the eventual enrollment in medical school. Although the camp in Ohio did not precisely track its participants, Rosenthal estimated that as a professor at Northeast Ohio Medical University, he would have about three students in his class each year who were former MedCampers, as they were called there. And that’s at just one of eight medical schools in Ohio; former campers could have gone on to another medical school in the state or country.

“The key here is, Las Vegas needs future physicians. We need a pipeline to get our bright, young individuals to see medicine as a real possibility,” Rosenthal said. “Because if we convince our own to go into the discipline, they’re more likely to come back and practice here, and improve medicine here in Las Vegas, because we need that.”

Engaging students at this age — just before high school — is intentional because it’s a time when students either choose to immerse themselves in academia or skate through high school.

“A lot of kids think that they don’t have the opportunity, or that they’re not smart enough, so we want to give them just that excitement,” Mara Hover, the physician mentor for the radiology group and associate dean for clinical education at Touro University Nevada, said.

On the final morning, the future doctors presented their findings before their families in a mixture of complex scientific terms and 14-year-old parlance.

Tawatao’s radiology group explained the meaning of the chest, hand and leg X-rays and the brain scan to the audience, extrapolating that Trepost must have an autoimmune disease that caused antibodies to attack healthy tissue in his joints and bones. The final group, speaking as cardiologists, announced the patient’s diagnosis: rheumatic fever resulting from untreated strep throat.

Then, in a graduationlike ceremony, each student was awarded the title “BD,” or beginning doctor. One degree down, only a few more to go.

Contact Sarah Corsa at scorsa@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0353. Find @sarahcorsa on Twitter.