Couple convicted of stealing friends’ retirement savings in his last years of life

After a lifetime of public service with the Navy and the Clark County School District, Elliott Smith died broke.

He thought he had hundreds of thousands of dollars, and certainly more than enough money to take care of his paralyzed wife, Sandra, for the rest of her dying days.

But only in the last months of his life, with a mind racked by dementia from Alzheimer’s, did he learn that his only living friends had stolen almost every penny, family members said.

He broke down and cried and never spoke of the friends again.

After a two-week jury trial that ended this month, 70-year-old Craig Ballew, a retired Clark County science teacher, and his 63-year-old wife, Ivy Rasmussen, who resigned last week as a guidance counselor at Mannion Middle School, were convicted of more than a dozen conspiracy, theft and elderly exploitation charges.

“They didn’t take care of him,” said Smith’s son-in-law, David Sweikert, who is retired from the Metropolitan Police Department. “They just took him.”

Ballew and Rasmussen were ordered held in the Clark County Detention Center until a January sentencing, but District Judge Stefany Miley is expected to consider bail Monday.

The couple used Elliott Smith’s money to buy everything from coffee and women’s hygiene pads to big-screen televisions and foreign cars, according to court documents.

Their attorney, Frank Cremen, said Smith would have testified on behalf of the defendants, if he were still alive.

After all, half the checks Rasmussen and Ballew were accused of having obtained illegally had been signed by Elliott Smith, Cremen said.

“There was vibrancy in my clients’ home,” Cremen said. “They offered him something other than glumness, and he chose that.”

■ ■ ■

By all accounts, Rasmussen and Ballew lived an affluent lifestyle long before the theft started.

When Ballew ran for a Summerlin-area Assembly seat in 2008, he boasted a proud résumé that encapsulated his 57 years in the valley. He had worked 36 years with the school district, coaching football and other sports.

Ballew and Elliott Smith developed a working relationship over more than 20 years at the schools. In retirement, they played golf together. Smith helped Ballew campaign for office.

In 2011, Rasmussen protested alongside teachers about school budget cuts. In 2012, she earned more than $100,000 with the school district, including benefits. She received a $4,000 pay bump the next year.

“I had worked with (Ballew),” said Smith’s stepdaughter, Sue Sweikert. “I knew they were Elliott’s good friends and they trusted him. I thought they were upstanding citizens. What they did was just heinous.”

In late 2008, Ballew and Rasmussen brought Smith in to their 3,000-square-foot, four-bedroom home with a pool and a half-acre lot along a cul-de-sac in the northwest valley.

Within months, Ballew was listed on Elliott Smith’s savings account. That same day, $50,000 cash was withdrawn. A day later, Smith withdrew $30,000.

■ ■ ■

The case started to unfold in late 2009, when Sandra Smith’s medical bills were $21,000 in arrears. Her husband thought he had set aside $300,000 to pay those bills as he continued to collect retirement checks from his career in the military and as a head custodian with the school district. He figured he was worth about $600,000.

Sandra Smith had suffered a stroke about three years earlier and fell shortly after being released from the hospital, breaking her hip. She would never return home.

Sue Sweikert obtained power of attorney to look into the Smiths’ bank records dating back to 2005. She found so much that she didn’t understand.

She discovered a $40,000 check to Desert BMW. Rasmussen told prosecutors she paid even more for the 2008 BMW 335i. There was another check made out to Desert Nissan for a 2008 Frontier. Elliott Smith told his family that the pickup was for Ballew and Rasmussen’s daughter, who had just earned her learner’s permit. They promised to pay him back, he said. They never did.

“I was shocked,” Sue Sweikert testified, “because he had never done anything like that.”

■ ■ ■

Her parents were modest and frugal, living in a single-story, two-bedroom, 1,000-square-foot home in North Las Vegas. It had been paid off for more than 30 years.

They mostly kept to themselves, gathering with family on holidays and the occasional dinner. They had more kittens than close friends. They shopped in their neighborhood. Their doctor’s office was less than a mile away.

For most of their marriage, Sandra handled their finances. Elliott took over after she was hospitalized.

Sweikert said her father never carried a credit or debit card. He didn’t have a cellphone and didn’t use the Internet. He wrote checks or carried cash.

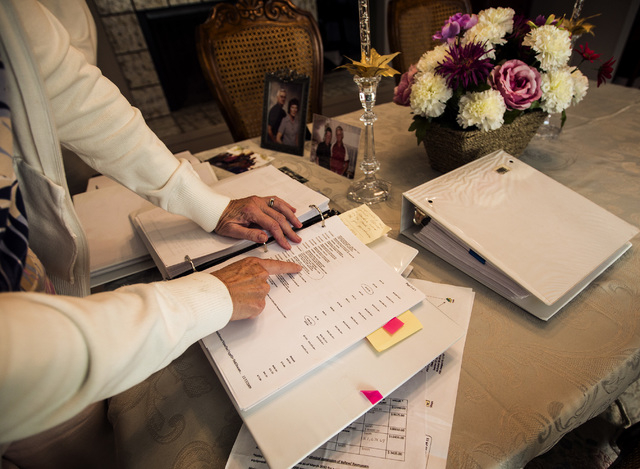

But the bank records — Sweikert has a binder full of them — showed purchases from Dillard’s, Ann Taylor, Sports Authority, Linens & Things, Bed Bath & Beyond, Williams-Sonoma, Trader Joe’s, American Eagle, Aeropostale and Victoria’s Secret.

She found 500 transactions totaling more than $82,000, ranging from a $4.15 debit card purchase at Starbucks to a $1,600 charge at Costco.

Ballew and Rasmussen shopped while Elliott Smith was in the hospital, hooked to intravenous drips and a defibrillator.

They would use their own membership card to get inside Costco and swipe Smith’s bank card at checkout.

They bought at least five televisions, shutters for their home and bicycles for their daughters.

They had Elliott Smith sign over three vehicles — a 2005 Mercury Grand Marquis, a 2007 Mercury Grand Marquis and a 1998 GMC Sierra — to them and sold the oldest Mercury without giving him the cash.

■ ■ ■

Though they both had previous marriages, Elliott and Sandra Smith loved each other so much in 40 years that they never bothered to hide their affection, even in their frailest moments.

When his wife was bedridden, Elliott Smith visited her every day. Sometimes, he struggled to rise from his wheelchair and kiss her cheek. He hung his head ashamed, then rolled up to her, kissed her hand and called her “lover.”

After Sandra Smith was hospitalized in 2006, the couple decided to sell their home for $125,000, collecting about $110,000 after transaction fees.

Sweikert asked Elliott Smith to stay with her family.

“I knew he was lonely,” she told a grand jury.

But Elliott Smith was a little stubborn, too. He found a place at Destinations at Valley View, a senior living complex.

Ballew helped him clean out his old home and move into his new apartment. He stayed for about seven months before telling family he was moving in with Ballew and Rasmussen.

Perhaps Rasmussen and Ballew initially wanted to help Elliott Smith, but Sweikert said that assistance was overtaken by greed.

■ ■ ■

Rasmussen and Ballew do not believe they coerced Elliott Smith into signing the checks, their lawyer said.

Elliott Smith approved of the bank card purchases Rasmussen and Ballew made while he was in the hospital, according to the attorney, and they reimbursed Smith for personal items they bought. He died in February 2010 at age 84, about a month before Ballew and Rasmussen were arrested.

“The case could have gone the other way,” Cremen said. “It would have been nice if Elliott were alive and could have testified. I have no doubt if he were, the outcome would have been different.”

But his dementia had grown so bad, family members said, that even if he lived to the trial, he would have been unable to understand the proceedings.

Cremen disagreed.

“Dementia is not the equivalent of incompetence,” he said. “It’s a symptom of a memory problem.”

Elliott Smith would sometimes confuse Ballew for his own son and Ivy for his wife or daughter.

Smith suffered from other ailments, such as vitamin B12 deficiency and hypothyroid that could have aggravated his condition.

Those conditions can worsen dementia, and Smith was stubborn about taking his pills.

Las Vegas police detective Gabriella Hatfield-Cook said elderly victims are sometimes taken advantage of because they have diminished mental capacity and physical disabilities, which make them dependent on other people. Often, they don’t want family members to know. The detective was familiar with Elliott’s symptoms because her own mother suffered from a similar form of dementia.

“The elderly person does not want to be looked at as all of the sudden I can’t take care of my issues anymore,” she told the grand jury. “In elderly exploitation cases, there are very vulnerable victims, and a lot of times they are also the ones who have amassed all their savings and everything over their lifetime. So they make very nice victims for the suspect.”

■ ■ ■

Prosecutors and the Smiths’ family believe Rasmussen and Ballew arranged to have their names used as emergency contacts for Elliott Smith so they could control information about his dementia.

In January 2010, the Sweikerts went to Ballew and Rasmussen’s home to pick up Elliott Smith’s possessions.

They found his pills scattered on the floor, in a shredder and in potted plants. They also spotted a picture on a bookshelf. It was a studio portrait of Elliott Smith’s grandchildren, daughter and late son — the family dearest to his heart. At his North Las Vegas home, Smith kept the photograph in an elaborate oak frame. In Ballew’s home, the frame had been replaced with a cheap plastic border emblazoned with the word “Friends.”

They asked for Smith’s wallet. Ballew pulled it from his back pocket, exposing a $500 dividend check endorsed by Smith four months earlier, and a Painted Desert Golf Course membership in Elliott Ballew’s name.

Police initially questioned Elliott Smith and Ballew together in April 2009 and determined there was no criminal case.

“It’s my money, and I’ll do what I want with it,” Smith told the investigators.

But his family said he suffered from what’s known as “sundowners syndrome,” in which someone is lucid in the morning but his memory grows worse in the evening. They believe Ballew and Rasmussen had Smith sign checks at night.

Posing as his daughter, Rasmussen had accompanied Elliott Smith to a doctor, who diagnosed him with dementia three years earlier. She never told his family.

Ballew and Rasmussen were convicted of stealing more than $150,000 from Elliott Smith, but his relatives believe they took much more.

Smith told his granddaughter that he had placed $125,000 in a 24-inch-by-24-inch safe. When family members opened the safe, they found $14,000, some of the bills scattered throughout the safe, and a death notice for Elliott’s son.

The jury acquitted the couple of taking the cash.

■ ■ ■

Prosecutor J.P. Raman said in cases of elder abuse, there are even some misunderstandings within law enforcement about what can be proved.

“Elder abuse is one of the least reported and prosecuted crimes,” Raman said. “There’s a lot of misconceptions about what elder abuse is and the provability of it.”

Cremen believes the elderly exploitation charge “has been inadequately defined by the state Legislature.”

That’s the most serious count in Rasmussen and Ballew’s conviction, carrying a sentence of two to 10 years in prison, though they also could be given probation. The judge is slated to sentence them in January.

Before she died at age 82, Sandra Smith told her daughter: “Sue, I know I won’t live to see it, but I hope the sons of bitches go to prison.”

Contact reporter David Ferrara at dferrara@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-1039. Find him on Twitter: @randompoker