UNLV team finds evidence of extinct wolf

The Pleistocene predators are starting to pile up in the fossil-rich hills at the northern edge of the valley.

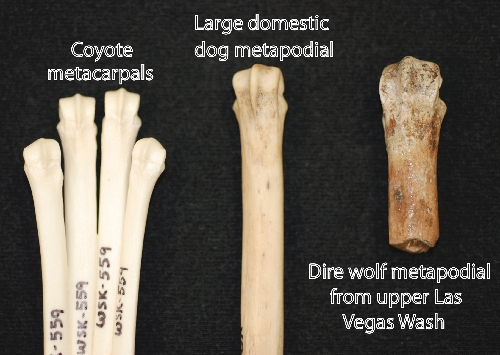

Less than a month after a California team found evidence of a saber-tooth cat in the Upper Las Vegas Wash, UNLV researchers announced the discovery of a 1½-inch long foot bone from what they believe was a dire wolf that stalked the valley between 12,000 and 15,000 years ago.

It marks the first time the extinct species of wolf has been found in the 22,650-acre swath of desert proposed for designation as Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument.

Josh Bonde, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, made the discovery. He was surveying a 160-acre plot of state land near Floyd Lamb Park this summer when he spotted the tip of the bone sticking out of a hill. The piece that was showing was no bigger than a quarter, he said, "just enough to identify it as a dog."

After carefully unearthing and processing the fossil, Bonde took it to the lab of zooarchaeology and anthropology professor Levent Atici, who maintains what is known as a comparative collection of animal bones.

"He started going through his dog drawer, and he said, 'Man, this is a great big dog,' " Bonde said.

Enter longtime UNLV geology professor Steve Rowland, who is collaborating with Bonde on a study of local ice age fossils. Rowland sent a photograph of the bone to Xiaoming Wang, curator of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and one of the world's leading experts on ancient carnivores, especially canines. Wang identified it as a bone from the foot of an extinct wolf.

Rowland and Bonde are convinced it belonged to a dire wolf, but there is a small chance it could be from a gray or even a timber wolf.

Rowland is headed to California for a field trip with students next week. He plans to bring the bone with him so he can compare it with the thousands of dire wolf fossils in the collection at the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

This isn't the first big find for Bonde, who specializes in much older mysteries. The geologist and paleontologist previously discovered roughly 100 million-year-old dinosaur fossils in Valley of Fire and the mountains of central Nevada.

The dire was one of the largest wolves to have ever lived, weighing about 150 pounds with thicker, shorter legs and a wider mouth than its modern equivalent.

Bonde said there is debate about how the animals behaved. Some believe they hunted their own prey; others portray them as scavengers, the ice age version of hyenas.

But like their present-day cousins, they were probably social animals. "These were packs of big old wolves," Bonde said.

As for the name, Rowland said, "it means a bad thing is about to happen if you see one of these. A ferocious wolf - that's what it implies."

The approximate age of Bonde's speciman is not known. Rowland said the bone is so small that they couldn't sacrifice any of it to get a radiocarbon date from it. They hope to pin down how old it is by testing snail shells, charcoal and other "datable material" found nearby.

Bonde and company have returned to the site in search of more wolf fossils. None has turned up so far, but they have found camel bones and other items of interest. "It's been a pretty fruitful little area," he said.

The adjacent federal land is loaded with old bones as well. Working under a contract with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, a team from California's San Bernardino County Museum has pulled thousands of ice age fossils from the area, including the unprecedented recent discovery of bones from a saber-tooth cat.

Before the cat and the wolf fossils were found, no predators had been positively identified in the Upper Las Vegas Wash since the jawbone of a North American lion was found there in the early 1960s.

Researchers long suspected that more meateaters must have lived here because of all the meat that was available back then, but finding predators in the fossil record is rare.

Asked what other fossils might be hiding in the wash, Bonde said, "If I'm going to get greedy, I guess I'd like to find a cheetah."

Since the researchers began surveying the pocket of state land in the Las Vegas Wash in 2010, they have turned up ice age bones of mammoths, camels, bisons, birds, rodents and reptiles.

The fossils they collect are processed in a lab at the Las Vegas Natural History Museum on Las Vegas Boulevard just south of Washington Avenue. Bonde said he and his team are there most weekends, covered in dirt and hunched over their latest finds. Visitors to the museum are welcome to watch them - even ask questions - while they work, he said. "People can come in and enjoy the fossils from their own backyard."

Bonde expects his team to be working out in his corner of the Upper Las Vegas Wash "for the foreseeable future."

They can't stop now, he said.

"Every time we're out there we find another site."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.