Website Nextdoor helps neighbors make connections, find sense of community

When Christine van den Brandt moved to Las Vegas after 16 years in Atlanta she had a hard time making personal connections with her new neighbors.

Lots of people just don’t like talking to strangers who approach them on the street.

“People just seem terrified of that,” van den Brandt said.

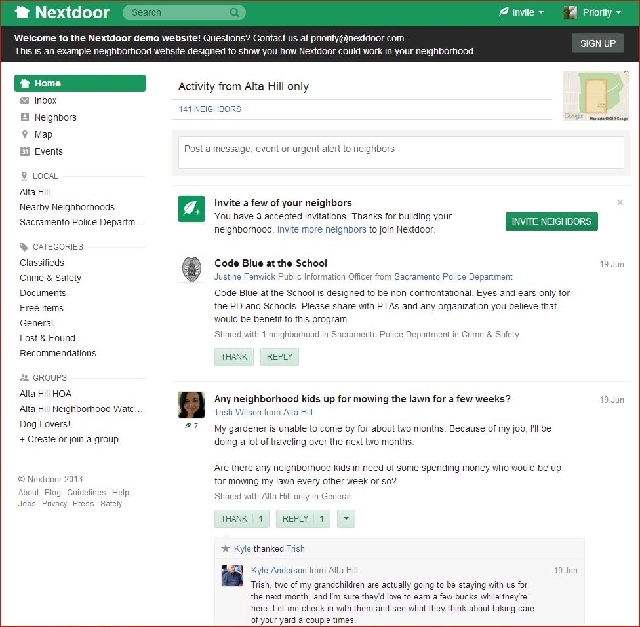

So she turned to the Internet and found herself on Nextdoor, a website aimed at using the Internet to connect people with their real-life neighbors.

Since then she’s connected with neighbors who have hired her for photography and commiserated about security of the neighborhood pool.

The site, which recently launched a mobile app, helped her find a sense of community with her neighbors, something that’s not always easy in Las Vegas.

“It just seemed like a much better idea than the old-school bulletin board nobody looks at,” she said.

According to San Francisco-based Nextdoor, the site has more than 14,000 neighborhoods in all 50 states. The company says it has 59 neighborhoods in Las Vegas, although levels of participation vary.

In van den Brandt’s neighborhood she estimates about 20 percent of approximately 100 homes participate.

Nextdoor has been live since 2011 but the company is only now releasing a mobile app. That’s in large part because of a desire by the founders to focus on making the website functional and useful before moving onto a mobile project.

Also, according to a company profile in Wired magazine, Nextdoor used in-house staff to create the mobile function, and they needed time to shift from website to mobile development.

It took longer than it would have had they hired mobile developers but, Wired reported, the benefit was having people who were familiar with the goals for the product as opposed to newcomers who might have development skills but less understanding of customer needs.

But a patient, methodical approach to development isn’t the only way Nextdoor is different from other interactive platforms, such as social networks like Facebook.

Rather than seeking to gain many users as quickly as possible, Nextdoor is much more selective.

People can sign up for Nextdoor online, but before they can participate they have to have their physical address verified. This is to ensure that only people from a particular neighborhood can participate.

New people can be invited in via postcards that, again, ensure the only people participating in an online neighborhood are those who live in the same, real-world neighborhood.

“We’re trying to create a safe place for neighbors to share something online what they would share offline,” CEO Nirav Tolia said.

“We are a throwback, we are about very deep, high-value connections in the area that you live.”

The site blocks the addresses associated with registered sex offenders and bars any accounts that aren’t verified by a physical address, meaning users post under their own name, although they don’t have to reveal their exact physical address to the other users.

Still, it is a level of personal identity that likely would make anyone looking to cause trouble online find another site.

“You don’t join this to be a troublemaker,” Tolia said. “If you are a troublemaker you don’t want to tell people your name.”

In addition to a higher barrier to entry, Nextdoor differs from other networks by seeking to keep the conversation focused on neighborhood issues, such as lost pets, property crime reports and other localized problems.

It does so by de-emphasizing photos and requiring users to categorize their posts under labels that define them as classified ads, recommendations or other uses.

The result is more attention toward problem-solving and very few, if any, political rants, random jokes or Internet memes.

“On FB you have to see everybody’s politics and personal stuff,” van den Brandt said. “We talk about the neighborhood and that’s it.”

The site doesn’t charge users and so far, outside of funding from investors, doesn’t make a profit. Tolia said there won’t be any plans charge users or sell data.

One possible way to make money is to allow some form of neighborhood-based advertising, like a more localized version of the Yellow Pages, he said.

Contact reporter Benjamin Spillman at

bspillman@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0285 .