California inspection station protects agriculture, angers drivers

YERMO, Calif. - When a truck with a boat pulled into the right lane of this high desert outpost's border inspection station, it was literally hands on deck for Greg Du Bose.

And on the sides of the hull, the stern, the intake and exhaust pipes, the outboard motor's propeller and the short ladder next to it.

Du Bose, the station manager, and another inspector had to rub their hands over the boat in their search for tiny, fast-breeding and resilient baby quagga mussels - high on the California Department of Food and Agriculture's most dreaded pest list.

Less than a minute later, a U-Haul truck in the adjacent lane triggered a standard open-the-back inspection.

"Just like that, we're down to one lane," Du Bose said. "If we get another box truck, traffic comes to a standstill."

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, it didn't matter much. There was no backup during the few minutes required to pronounce the boat and the U-Haul clean and to let their drivers continue southward on Interstate 15.

But when tourist hordes decamp Las Vegas on a Sunday or after a holiday weekend, the car lines quickly grow to lengths best measured by an odometer. Ten-mile backups are not unheard of.

"We hear more complaints about Yermo than anyplace else," said Lance Todd, program director for Highway Radio, a Barstow, Calif.-based operation that closely monitors I-15 traffic. "It is the worst bottleneck on a regular basis. There's no place else where you are required to stop or slow down to see if you are supposed to stop."

When Las Vegas officials look at Yermo, nearly 140 miles southwest of the Strip, they see an economic headache.

"If I were caught in that line, especially when the temperature is 115 in the summer, I would think long and hard about when I am going back to Las Vegas," Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman said. "To me, the best thing they could do is just flatten it. I don't see what good it does."

TRAFFIC INCREASES

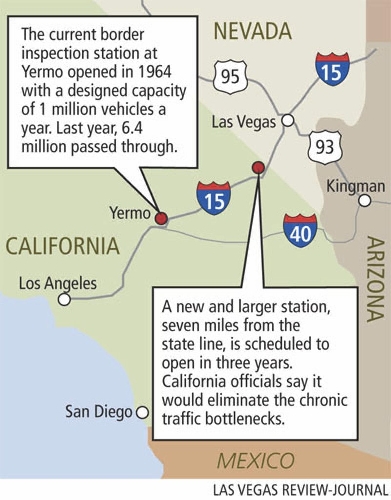

Built in 1964 to handle 1 million vehicles a year; the Yermo border inspection station saw 6.4 million in 2011, split between 1.1 million trucks and 5.3 million private cars.

And even as traffic volume has grown, Du Bose said, state budget woes have reduced the staff to 10 permanent and two temporary inspectors where there once were 18 to 20 permanent positions.

While the hard-pressed inspectors check most commercial trucks, many private vehicles with Nevada and California plates routinely are waved through without even a question about fruits, vegetables or plants they might carry. That leaves some locals to wonder how the place they call "the bug station" contributes anything to Du Bose's mission of "minimizing the spread of invasive and evasive species that could find a home here in California's agricultural industry."

Nevada transportation consultant Tom Skancke, recently named president and CEO of the Las Vegas Regional Economic Development Council, doubts the need for the station. But, he adds, "We have to respect other state's laws."

Inspectors generally profile vehicles, license plates and contents - not the people - in deciding who to inspect.

"In the professional world, you are supposed to make eye contact,'' Du Bose said. "Here, we are looking around you."

In doing so, inspectors play probabilities and don't expect to catch everything. Fewer than 1 percent of the vehicles are classified as intercepts, where flora and fauna violating California regulations are seized.

PROTECTING AGRICULTURE

But to the west, the inspections have many defenders. The Yermo site is part of a state network of 16 stations spread from Oregon to the Mexican border, the front line in defense of California's $43.5 billion agricultural industry.

"It is an important part of the infrastructure," said Rayne Pegg, of the California Farm Bureau Federation. "Most people overlook how very costly it is to eradicate a pest once it's inside the state."

One study cited by the agriculture department shows that each dollar spent on inspections saves $14 in eradication expense and crop losses.

Inspector Derek Wilson said Las Vegans don't understand the purpose of his job.

"They see it as blocking traffic,'' he said. "I see it as helping to protect California."

Skancke said a solution to the traffic backups is near. California plans a new station just seven miles from the Nevada state line, within sight of the casinos and hotels at Primm. Called the joint port of entry, it would also house the California Highway Patrol's commercial truck safety and weight checks.

California Department of Transportation project manager Jason Bennecke said the new $62 million station should eliminate traffic snarls. Plans include a widened approach, two more car lanes than Yermo has, two more lanes for commercial trucks, and a lot where vehicles requiring extra attention can be moved out of the traffic flow.

At Yermo, Du Bose pointed out that Interstate 15 is only two lanes wide until a couple of hundred feet before the station. When truck traffic backs up, passenger cars are effectively funneled into the left lane or trapped between slowly accelerating trucks. Widening the highway to at least three lanes was planned several years ago, he said, but dropped in favor of an all-new station.

California plans to buy land for the new outpost this year, then start with construction of the CHP commercial truck facility. The entire project would be done by 2016.

But that timetable is far from certain. The idea has been discussed for more than two decades, and at least one prospective ribbon-cutting has evaporated because of budgetary and other snags.

CALCULATING ODDS

For untold eons, nature served as California's inspection station. Few pests made it across the Pacific, deserts and impassable mountains to the lush Central Valley, where almost anything grows.

But railroads and highways create an easy ride for hitchhiking pests, such as wood-boring beetles, thrips, quagga and zebra mussels, and mealy bugs. To fend off the menace, California started inspections in the early 1920s.

The first Yermo station, still visible from the current one, went up in 1930, when there was no other paved route. It's now easier to bypass the station, one reason to move it closer to the state line.

The Marine Corps Logistics Base, a fixture at Yermo since World War II, once helped staff the station with troops looking to pick up extra money as part-time inspectors.

These days, the department and its inspector corps follow a protocol that any casino manager would comprehend, calculating odds that certain vehicles will be safe while others could carry pests. Private vehicles and commercial trucks get funneled into different lanes with different rules.

In light traffic, said Du Bose, most drivers are asked to roll down their window and answer questions about any fruits and vegetables they have, although locals such as Goodman can't recall ever being stopped.

When it gets busy, cars with Nevada and California plates are waved through unless inspectors spot something amiss. The reason, said Du Bose, is Nevada's climate and the "concrete jungle" of Las Vegas spawn no worrisome pests. In addition, Nevadans generally spend little time in Southern California, while Californians seldom venture past the Strip.

The quagga mussel, which chokes out other forms of aquatic life, is the notable exception. First detected in Lake Mead five years ago, their population is now estimated at 1.5 trillion adults and 320 trillion babies. Boats found to carry the mussels are pressure-washed on the spot.

But even in busy times, Nevada and California plates do not confer automatic immunity. Du Bose recalled stopping a driver hauling a load of Ponderosa pine. While the driver insisted the wood was not prohibited, Du Bose broke off some bark and found a half-dozen wood-boring beetle larvae, resulting in confiscation.

"Bringing in the wood is OK; the pests are not," he said.

The sight of a cooler will prompt a carefully worded question from an inspector. Asking generally about a container's contents can make drivers feel they are being called liars after initially saying they have no fruits or vegetables, Du Bose said.

"You want to have the public on your side so they cooperate with you instead of opposing you," he said.

Cars from other states are sometimes physically checked. A driver recently was asked to open the trunk of his Tennessee-registered sports car, not because the inspector thought he was hiding anything, but to check for stowaways in the insulating strip around the trunk's edge.

"Sometimes, pests can fall from trees and get in there without the driver even knowing it," Du Bose said.

Likewise, inspector Andrew Maes opened the back of a trailer towed by a truck with Texas plates. Ignoring the jumble of furniture inside, he checked the rubber door gasket for the fire ants that proliferate in Texas.

Any animal cages or food bring questions. Most pets are fine, but animals banned in California, such as ferrets, are seized and placed with a shelter.

Fruit is profiled: Foreign oranges have thin rinds. Fuzzy navels or bruised skin prompt an examination with a microscope in a small room near the inspection lanes, and reports to headquarters in Sacramento.

Contaminated pieces are double-bagged for disposal in the deepest part of a county landfill to prevent pests from escaping, Du Bose said.

Stumbling across other substances - I-15 is a major cocaine trafficking corridor, Du Bose noted - will not prompt an arrest but perhaps stalling while notifying the CHP or other officers.

"We are not law enforcement," Du Bose repeatedly tells his crew.

One night on the graveyard shift, Du Bose recounted, a driver insisted the trailer he was towing was empty. But Du Bose noted an unusually tiny gap between the tires and fenders, so he opened the back and found 22 illegal aliens inside. At that point, he turned the matter over to the CHP.

Some commercial trucks can roll through nonstop, such as those working for Macy's or some of Wal-Mart's fleet. Others must present paperwork showing their load meets California standards.

Luis Camargo had to take an unexpected break at the station, as he hauled moving containers filled with people's possessions on a trip that had started in New York state. Without proper documentation, he wasn't going anywhere.

"Only California and Florida are like this," he said, as he struggled to get a cellphone signal to his home office.

But to show up without papers, said supervisor Elliot Morris, "They should know better than that."

Some cargo requires special attention. A truckload of bees was pulled to the side while an inspector donned a white suit with a mesh face to get a closer look. Inspectors keep photos of car hoods and fenders coated with bees that escaped during previous inspections.

For the sake of variety, inspectors work a constant rotation: 15 minutes in each of the three car lanes and 15 minutes on the truck lane, before repeating the cycle.

Although many are from the area and are acclimated to searing summer heat, sharp winter chill and near-constant wind, they still have to make adjustments. Small booths on each lane have portable heaters this time of year, but Du Bose cautions that constantly alternating between indoor warmth and outdoor cold will almost certainly cause inspectors to start nodding off.

In the summer, the station wheels out giant humidifying fans, similar to those used on NFL sidelines. For the nonstop noise, "We have an ample supply of earplugs," Du Bose said.

But there's no way to filter out another fact of life as an inspector.

"Smell that?" Du Bose asked as the wind caught the odor of a truck carrying about 100 live hogs.

Contact reporter Tim O'Reiley at toreiley@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290.

Five of the Most-Wanted Pests at Yermo Agricultural Inspection Station

• Wood-boring beetles: Can infest both live trees and harvested wood, even timber used for homes and furniture. They cause damage or destruction by chewing through wood.

• Thrips: Slender insects that feed on vegetables and developing flowers and transmit plant viruses. Thrips cause deformities and discoloration that drop the value of commercial crops.

• Quagga mussels: Tiny mussels that breed rapidly, choking out other life in bodies of fresh water and rivers. First discovered in Lake Mead in 2007.

• Small hive beetles: Found in bee hives, they destroy honeycombs, bee colonies, honey and pollen.

• Mealy bugs: They feed on the juices of citrus fruits, grapes and pineapples, as well as greenhouse plants such as orchids.