CARRYING A BURDEN FOR THE LOST

This is the second in a four-part series.

LAST SUNDAY: Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan routinely overcome horrid wounds and loss of limb, but equally formidable foes are the mental effects of head injuries, constant or repeated exposure to danger and making decisions of awesome consequence.

TODAY: When an American dies in combat, the warrior's loss leaves a hole in American hearts.

More than two years after Army Spc. Ignacio Ramirez's death, seven boxes of his personal things from Iraq sat sealed and untouched in his mother's Henderson home.

Finally, in August, Marina Vance opened the packages to reveal the clothes, CDs and other items that were owned by her 22-year-old son when he and two fellow soldiers were killed by an improvised explosive device in Ramadi.

The tenuous illusion that her boy, Nacho, might one day walk through her front door, was shattered that day.

"He won't," she said in a recent interview. "He's gone, and he's not coming back."

Nearly 4,800 U.S. lives have been lost in the U.S.-led global war on terrorism. Sixty-one of those U.S. military personnel have had ties to Nevada.

As part of a series of stories on how war affects people back home, the Review-Journal visited with three local families who this year commemorated the second anniversary of losing a loved one in Iraq or Afghanistan.

The newspaper found that long after the memorial services ended and the condolence letters ceased, the deaths of the servicemen still profoundly impact the lives of those left behind.

Their losses have made war intensely personal. They prefer not to think about the politics of it all.

"I guess after a year, people pretty much stop calling," said Perneatha Evans, whose husband, Air Force Capt. Kermit Evans, 31, was killed in Iraq in December 2006. "It's not your first Christmas, so everybody thinks you're all right. But after you've gone through all your firsts, you're still not all the way there."

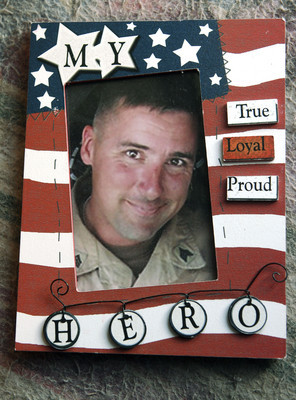

Christa Griffith said she still panics a little when she hears the doorbell chime at her Henderson home. It takes her back to the morning in May 2006 when an Army official came to tell her that her husband, Sgt. John Griffith, had been killed in a helicopter crash during combat operations in Afghanistan. He was 33.

"It's been 21/2 years, and now there are more smiles than tears, but it's not something you ever get over," Griffith said.

'A piece of my home'

Marina Vance has devoted a sizable portion of her living room to the memory of her son. A makeshift shrine with photos, childhood toys and Army medals is illuminated 24 hours a day by an overhead light.

"This is home, and he deserves a piece of my home," Vance said, gazing at a large framed portrait of her son in a Little League baseball uniform.

Some photos in the personal gallery show Ramirez before deployment: smiling, baby-faced, delicate. In the Little League picture, his bat is cocked, ready to swing.

Others show him in military clothing during deployment: scowling, intense, hardened. In his Iraq picture, a magazine is in his rifle, ready to shoot.

Ramirez's mother, stepfather and six siblings never got to see the fun-loving Nacho come home.

The last glimpses of his sense of humor came in letters he sent from the battlefield.

He wrote a long one to his 13-year-old sister, Tia, dispensing brotherly advice and playfully warning her not to date any boys until "you are 70 years old."

It's part of the shrine and a reminder that the young soldier who took orders in Iraq was a leader at home.

Tia and her brothers and sisters try to remember good times they had with Nacho. "He made us all smile. I'll always remember that."

Marina Vance pays a lot of attention to the names that get added to the list of war dead.

"I know what all their families are feeling," she said. "I know how hard it is."

Vance is a member of the Blue Star Mothers of America, a support group for mothers whose children have served in the military. Some members have lost sons in the current wars.

On Veterans Day, joined by several other mothers in the group, Vance stood over her son's grave at the Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City.

"They offered me to bury him in Arlington (National Cemetery)," she said. "I said, 'No, he's coming home.'"

HEALING TOGETHER

Perneatha Evans' 3-year-old son, Kermit Jr., was just an infant when his father's helicopter crashed during an emergency water landing in Iraq's Al Anbar Province, killing him and three other servicemen.

The couple had been married two years. They had planned to move to New Mexico after Kermit Sr.'s deployment was over.

"It was a lot to comprehend," Evans said from her North Las Vegas home. "Now the person's here, now they're gone. And now you have a child to raise all by yourself."

How would she explain to her young son what happened? And when would be the right time?

The moment came a month or so ago.

Mother and son were looking at a photo album with pictures of Kermit Sr. when Evans for the first time told her son directly, "Daddy died."

Evans said her son's answer brought tears to her eyes: "He looked at me and said, 'Daddy didn't die in the water. He's in the sky far, far away.'"

It was a big step forward, she said, a sign that she and her son are learning to deal with tragedy.

"Just as I've been enclosed, he's been enclosed," she said.

Evans said she put a lot of her energy since her husband's death into getting a master's degree in global leadership through an online program at the University of San Diego.

It was an abrupt change of course for Evans, who studied microbiology at Mississippi State University in Starkville.

But it was something she did to honor her husband, whom she met in college.

"I wanted to understand leadership the way my husband did," she said.

Her next goal is to try to get a statue of Kermit Evans put on the campus of their alma mater.

In the meantime, she and her son are adjusting to becoming a new kind of family.

The two recently returned from a trip to Disneyland with Snowball Express, a nonprofit group that organizes activities for the children and single parents of fallen military personnel.

"We'll make it," she said.

A FAMILY SPLIT

Christa Griffith and her husband were high school sweethearts who came together again later in life and got married.

They had been husband and wife for only a month when John Griffith's Army unit was deployed to Afghanistan.

Fifteen years after first meeting at Eldorado High School, they were looking forward to together raising her two children and his daughter when he got back from war, Christa Griffith, herself an Air Force veteran, said.

A few weeks before he was due home on leave, a CH-47 Chinook helicopter crashed in eastern Afghanistan, killing Griffith and 10 others.

Griffith's death touched off a family dispute that lingers to this day.

A series of disagreements between Griffith's wife and parents flared up over survivor benefits and burial rites.

John Griffith's parents got custody of granddaughter, Kailynn, who's now 10.

"We all loved John in different ways, and we all lost him in different ways," Christa Griffith said. "When he died, it became a family disaster. It's been like losing him all over again."

Barbara Griffith, John Griffith's mother, said she and her husband are honoring their son's memory by raising his daughter the best way they know how.

"Our only focus right now is this child," she said. "Her emotional well-being is everything."

Without a family network, Christa Griffith has sought outside help.

She is a member of the local chapter of the Gold Star Wives of America, a 63-year-old organization of widows and widowers of military personnel who died while on active duty or in a service-connected role.

She also consults with the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS), which offers help to anyone who has lost a loved one in military service.

"They've taken my calls at 2 a.m. when I couldn't see straight," she said. "That is what I still go through sometimes."

• • •

Marina Vance closes a wooden trunk full of newspaper clippings, letters, and other remembrances of her son.

Christa Griffith prepares dinner in a house with pictures of her new boyfriend, a soldier now serving in Afghanistan.

Perneatha Evans laughs at the memory of something her husband told her from Iraq about raising their son: "He said, 'Just get him to walking, and I'll take care of him from there.'"

He never got to see his son's first steps.

But now that he's walking and talking, his mother said, he looks more like his father every day.

Contact reporter Alan Maimon at amaimon @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0404.

ON THE WEB View the slideshows VETERANS SERVICES Nevada Office of Veterans Services (south office) 950 W. Owens Dr. Room 111 Las Vegas, NV 89106 (702) 636-3070 www.veterans.nv.gov Nevada Office of Veterans Services (north office) 5460 Reno Corporate Dr. Reno, NV 89511 (775) 688-1653 www.veterans.nv.gov VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System 901 Rancho Lane Las Vegas, Nevada 89106 (702) 636-3000 www.lasvegas.va.gov Wounded Warrior Project (877) 832-6997 www.woundedwarriorproject.org