Defining kidnappings among disagreements

ATLANTA -- Authorities count hundreds of Amber Alert cases as success stories when they explain why the popular bulletins are so important.

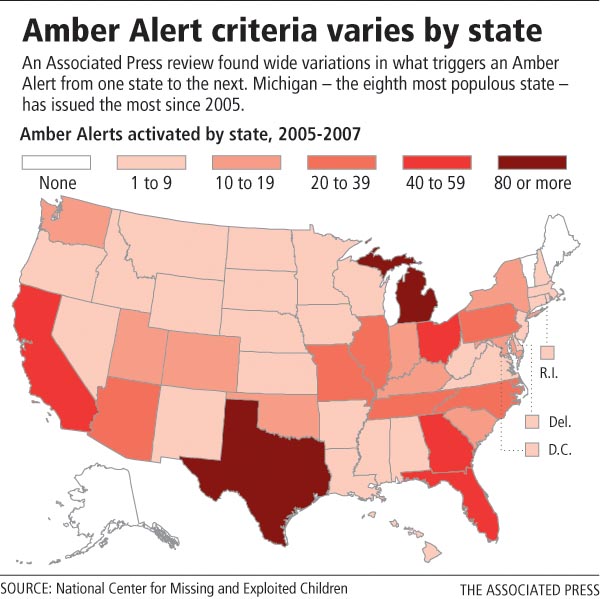

Yet despite a federal law meant to create a uniform system, what triggers an Amber Alert varies widely from one state to the next.

Records show some states barely keep track of Amber Alerts they've issued, let alone whether they worked. That poor record-keeping makes it difficult to tell whether investigators have ever missed a chance to safely recover an abducted child because of differences in the state laws and their application.

Twelve states refuse to put out an alert when a parent calls police amid a custody fight, while others see that as a legitimate reason to enlist help from the public. Twelve states issue Amber Alerts for adults with mental or physical disabilities, while other states save their bulletins solely for abducted children.

A 5-year-old federal law requires that every state have a child abduction alert system in place. The law also requires that those systems be uniform to help coordination and that the U.S. Department of Justice appoint someone to get the states on the same page.

But New Jersey has issued four alerts since 2005, while Michigan has issued 100.

Critics question the basic premise of Amber Alerts, that they help find and save abducted children. Kidnappers who kill children usually do so in the first six hours after they take their victims, experts say. It often takes that long just to get an alert issued.

A few days after she disappeared in April 2006, 10-year-old Jamie Rose Bolin of Purcell, Okla., was found dead in a neighbor's apartment, the victim of what investigators said was a cannibalistic fantasy. Police did not initially put out an Amber Alert, because they suspected she had run away and they had no reports of an abduction.

An alert eventually was issued, but police said the girl probably was killed the day she was taken.

Law enforcement officials insist the alerts can be crucial to recovering endangered children, even when multiple states are involved.

Take the case of Jerry Jones, who killed his infant daughter and his ex-girlfriend's parents and sister in a Georgia town before kidnapping the couple's other three kids. Motorists saw an alert on a highway sign and spotted the Ford Explorer driven by Jones, who was caught just across the Tennessee line and was given a death sentence this year.

The three children were found safe, and the Levi's Call, as Amber Alerts are known in Georgia, "was the key to the whole thing," said John Bankhead of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Amber Alerts started in 1996 after the murder of 9-year-old Amber Hagerman, who was kidnapped while riding her bicycle in Arlington, Texas. The city developed a system where police work with broadcasters to put out bulletins on abducted children, similar to severe weather warnings.

Soon, other states began creating Amber Alert systems, and Congress established its own law in 2003.

The federal law sets basic standards for issuing an alert but doesn't penalize states that don't follow them.

The law set aside $20 million to help establish and shore up state highway alert systems. About $4 million remains unclaimed, and 10 states haven't applied for any of that money.

Every state has an alert system. Federal authorities have no intention of asserting control of state systems, regardless of the law's establishment of a point person to do that.

"There will never be a federal Amber czar," said Jeffrey Sedgwick, an assistant attorney general at the Justice Department who spends part of his time as coordinator for the Amber Alert network.

States pay little attention to their alert programs and sometimes squabble over when to issue the bulletins.

In California, authorities will issue an alert in cases involving a custody dispute. Not so in Nevada, which claims to have the most stringent criteria in the country for sounding the alarm.

Also, California will issue an alert in the case of an abducted adult with a mental or physical disability. Nevada will not.

"A state that issues alerts more liberally may be miffed when a neighboring state is more conservative and won't do it," said Victor Schulze, deputy attorney general in Nevada. "But we're concerned that an overuse of the system will numb people to the emergency characteristic of it."

Schulze said Nevada has turned down alert requests from neighboring states because of criteria differences.

California has issued 66 alerts since 2005, while Nevada has put out seven, roughly the same rate per capita.

Record-keeping also varies drastically. In Utah, detailed records of each alert that has been issued are available on the Internet. Mississippi police have only handwritten files on the three alerts they've issued since 2005. That makes it tough to tell whether an Amber Alert makes a child more likely to be saved.