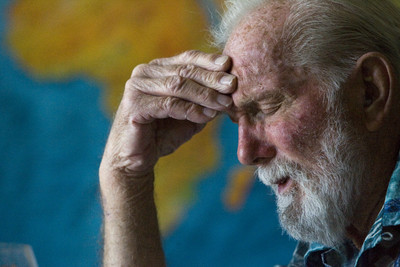

Former hostage awaits compensation, justice

Freedom was the reward Roland Bergheer got for surviving as a hostage and human shield in 1990 under the regime of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Now, 18 years later, the 80-year-old, German-born logistics expert who was working for construction giant Bechtel Group Inc., in Baghdad, says freedom still affords him and more than 200 others a chance to collect compensation from Iraqi government assets.

"My goodness. It's the very starting point of our democracy. Freedom says that we're allowed to do things that other nations are not allowed to do. ... That was taken away from me when I was a hostage," he said last week from his Las Vegas home.

The last of many promises for compensation failed in December when President Bush vetoed payment of claims of some $500,000 each to him and others as part of a defense authorization bill.

Bergheer said he is not giving up hope, though, that Bush or the next president will free up the funds.

"I would think that the proper thing for President Bush to do is get it passed before he leaves office," he said.

Bergheer believes that he and the other hostages deserve compensation because time and time again they supported whatever action Bush's father, then-President George H.W. Bush, would have taken to deal with Saddam in the weeks before the 1990 Gulf War.

"If President (George H.W.) Bush offered a pre-emptive strike, I would have considered myself expendable if the bombs started dropping. We were human shields," he said in an interview Tuesday. "Across the street was a rocket launcher. Oh my lord. Here we were on the verge of being killed."

Bergheer returned to Las Vegas in 1991, the year after his release, and has lived here ever since. Until 2004, he would split his time between his Las Vegas home and one in Spain.

But for more than four months beginning in August 1990, Bergheer was stuck in Iraq where Bechtel had sent him to arrange delivery of foreign supplies to build a petrochemical complex.

On Aug. 19, 1990, in the wee hours of the morning, he got a call from someone he didn't know who told him to pack a small bag, leave his room at the Baghdad Sheraton Hotel and go to the U.S. ambassador's home, a safe house where Americans were gathering. Saddam was preventing Americans from leaving the country after his tanks rolled across the Kuwaiti border on Aug. 2, 1990.

Saddam eventually allowed the women to return to the United States, but the men were confined to the residence. Later, some two dozen Kuwaiti nationals would take refuge in the house before fleeing to the airport.

From the onset, Bergheer served as the spokesman for dozens of hostages at the residence. The Iraqi army and later Saddam's powerful Republican Guard stood at the front and rear entrances, allowing only Bergheer and Acting Ambassador Joseph C. Wilson to travel to and from the home.

Routinely, Bergheer's deep voice and his fair-skinned cheeks poking from his snowy beard were the focus of internationally televised newscasts. His fellow hostages had elected him to be their collective face for the world.

Although he represented them, he was careful to speak in terms of his views.

Doing otherwise, he said, could have jeopardized his "brothers" at the ambassador's residence.

It was a precarious situation. In his comments to the media, he had to play a balancing act at the expense of being a pawn for Saddam.

"Saddam was already using me as propaganda. He'd say, 'Look at this man. He's not sick. These people aren't hostages. They're my guests,'" Bergheer said.

The lanky, former merchant marine who fled Hitler's Germany with his mother in 1935 and went on to serve for the U.S. military in three wars and became a U.S. citizen in 1944, never buckled to the notion of making deals to free hostages.

He said as much in the many interviews he gave journalists while he endured Saddam's grasp.

"I've always been totally opposed to negotiating in any way for the release of hostages. ... I don't think there should be any negotiating over a hostage because that could lead to more of the same," he told one ABC news reporter at the time.

In another interview, he expressed fear of being killed but noted that he was in good health even though morale was fading in the face of a U.S. airstrike that would then be the first salvo of war with Iraq.

"If it comes to that, then I still consider myself expendable in that regard. I feel that I'm an American and if it goes in that direction, that's the way it goes.

"It feels good that we've got such a great nation behind us. I'd just like to thank the Americans for thinking of us and giving us your prayers. It's a superb country. I'm proud to be an American," he said at the time.

Looking at it now, with flashbacks that bring tears to his eyes and add more wrinkles to his brow, Bergheer says the post traumatic stress disorder that he suffers from being a hostage overshadows any experience he had as a much younger man during World War II, and the wars in Korea and Vietnam.

"At Thanksgiving, it looked like we weren't ever going to get out alive," he recalled about the fourth month of the ordeal.

Food was already scarce and the "rednecks from Louisiana and Arkansas" who he said would sneak past the guards at night to secure supplies such as rice, potatoes and lentils could no longer take the risk.

They feared the soldiers would find them at the marketplace and shoot them.

Things changed abruptly though on Dec. 9. Wilson told Bergheer that Saddam was releasing all Americans. Apparently, the hostage-taking approach "wasn't doing what they expected," he said.

In hindsight, Bergheer said he thinks Russian officials played a role in their release.

One of them, he said, called Saddam and expressed dismay that among foreigners in the country were Russian citizens as well "who weren't allowed to leave. A lot of them were KGB agents."

Iraq's secretary of state was dispatched to Moscow "and the message was if you don't release all hostages immediately, we're considering sending troops down there to join the Americans," Bergheer said.

That evening, the Americans were given exit visas, bused to the airport, loaded on an Iraqi airlines 747 and flown to Frankfurt, Germany.

From there, Bechtel officials had arranged to fly him first-class to Los Angeles where he was reunited with his children, his brother's family, friends and co-workers.

"I broke down several times on that flight," he said. "I was an emotional wreck."

During the Gulf War, Bergheer said the United States "made a mistake" by not forcing Saddam to surrender.

He said he was elated when Saddam was captured, tried and executed more than a decade later during Operation Iraqi Freedom. "I got telephone calls from all over the place."

Even though Saddam is not a threat any more, Bergheer said in his opinion U.S. troops should continue to have a presence in Iraq for a long time.

"We should be there. Oh God, yes," he said. "I do not believe in cease fire.

"What does it mean? War doesn't stop."

And while the war goes on in Iraq, U.S. citizens are back in the country working to reconstruct it with Iraqi funds that Bush sent to the coalition, bypassing the hostages.

Daniel Wolf, attorney for the former hostages, has said that Bush was convinced by State Department staff that the reconstruction effort would have been jeopardized if the assets were tapped instead for compensation.

In fact, it was the State Department's ill advice to American workers in Iraq not to worry about Saddam's troop buildup in southern Iraq in the summer of 1990 that eventually caused the hostage ordeal.

For that reason, Bergheer feels President Bush is obligated to approve compensation before his term expires.

"It's a shame this president reneged," he said.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0308.