Hoover Dam delivered, but Nevada could have gotten more

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

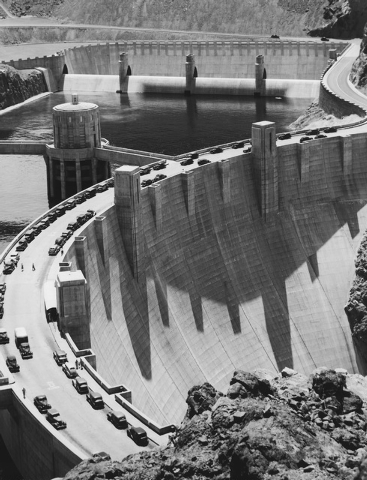

The most important structure ever built in Nevada is barely in Nevada at all.

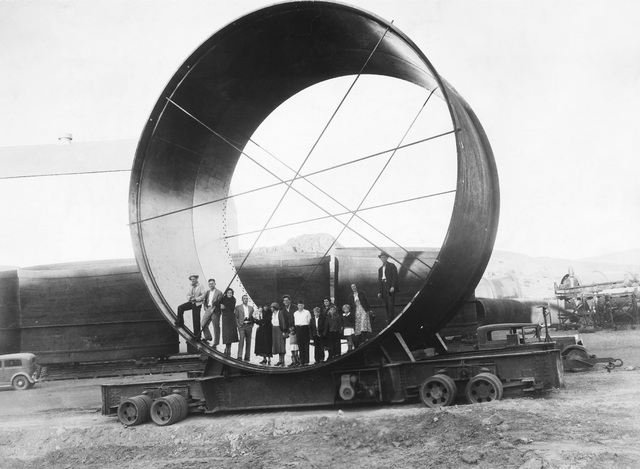

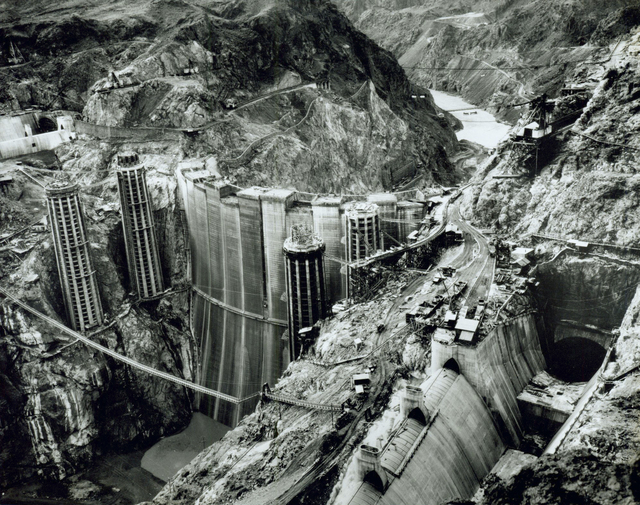

As large as it is, the entirety of Hoover Dam — the power plant, spillways, support structures and the dam itself — covers less than one square mile, and roughly half of that is in Arizona.

But its impact touches every square inch of the Silver State and a great deal of the Southwest. Take away all the water, power and revenue generated by that 6.6 million-ton concrete plug in Black Canyon and there would be no modern-day Las Vegas, no Boulder City, no Henderson. The state’s largest population center and its economic powerhouse simply would not exist, at least not as it does today.

This Oct. 31 would still be Nevada’s 150th birthday, of course, but without that dam you can bet there would be far fewer Nevadans around to celebrate it.

“If you’re looking for a single structure that had the largest impact on Nevada, it would be Hoover Dam,” state archivist Jeff Kintop said. “All the other big structures built down there (on the Strip) wouldn’t be possible without Hoover Dam.”

But as much as Nevada has gotten from the dam, it didn’t get as much as it could have. Back when the project was conceived and built, state leaders actually turned down the chance to secure more water for Southern Nevada.

“They didn’t think they needed it,” Kintop said.

WATER WASN’T A PRIORITY

Talk of trying to tame and harness the Colorado River began before Nevada earned its statehood, but Nevadans didn’t have a direct stake in the idea until 1867. That’s when the young state took possession of a mostly empty, triangle-shaped slice of the Arizona Territory just west of the Colorado. The acquisition included all of present-day Nevada south of 37 degrees latitude, including what is now Clark County.

The push to develop the river began soon after, though back then it was mostly seen as a potential route for Southern Nevada’s miners and farmers to ship products to market by way of the Gulf of Mexico.

When the focus shifted to diverting or damming the Colorado, state leaders mostly saw it as an opportunity to irrigate more cropland and power more mines. Providing river water to the tiny railroad town of Las Vegas wasn’t even part of the discussion, said Dennis McBride, director of the Nevada State Museum at the Springs Preserve, which was covered in free-flowing springs and streams in the 1920s.

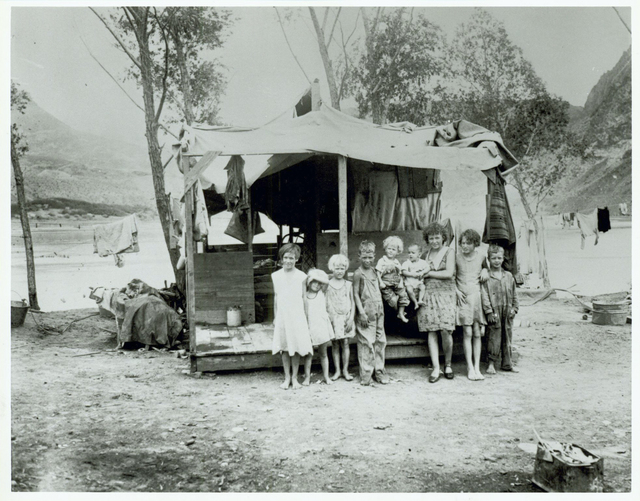

Back then, “there were only about 5,000 people in Southern Nevada, and we had plenty of water that came right out of the ground,” said McBride, a Boulder City native who has written extensively about Hoover Dam.

Locals first embraced plans to build what would be the world’s tallest dam just east of town not for any long-term benefits but for an immediate economic boost. McBride said Las Vegas was in the midst of a financial slump and “an identity crisis” in the wake of a 1922 railroad strike. Local leaders and civic boosters began lobbying hard for the dam because of the jobs and investment it would bring.

Kintop said it wasn’t a lack of enthusiasm that kept Nevada from getting all it could from the project. It was a failure of imagination.

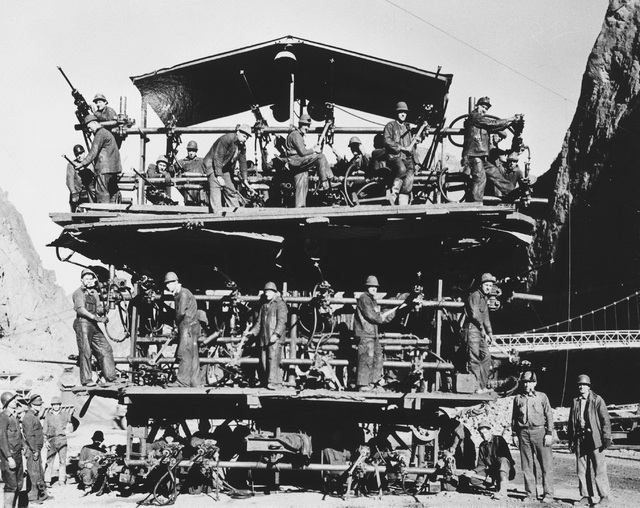

When construction began in Black Canyon in 1931, Nevada was home to fewer than 100,000 people, most of them in the northern half of the state. That Clark County, population 8,500, would one day support 2 million residents and 40 million annual visitors was beyond belief.

“It exceeded all expectations and agreements,” Kintop said.

So when the time came to divvy up the spoils from the dam, namely cheap water and power, Nevada officials were more interested in electricity. They wanted as much of it as they could get to power the mines and convert the local railroad to an electric line, Kintop said.

“They had a shot at more water, and they didn’t go after it,” he said. “They turned it down.”

As a result, Nevada wound up with an annual river allotment of 300,000 acre-feet, just seven percent of California’s 4.4 million acre-foot stake and the smallest by far among the seven states that share the Colorado.

It seemed like plenty at the time, but within 60 years of the dam’s completion water managers in Las Vegas already were floating plans to tap groundwater across a 300-mile swath of rural Nevada. By pushing for just a few hundred thousand acre-feet more back in the 1920s and ’30s, that controversial, multibillion-dollar scheme might not be needed for decades, if ever.

UNEXPECTED EXPLOSION

It didn’t take long for the state’s early lack of foresight to reveal itself.

The dizzying expansion of the Las Vegas Valley began during World War II and continued almost unabated through the economic collapse in 2007. Clark County’s population more than doubled, to 48,289, between the federal census of 1940 and 1950, then it nearly tripled to 127,016 in 1960. It would double or nearly double every decade after that, until 2010.

By some estimates, the community outgrew what the local groundwater supply could sustain sometime in the late 1940s. After that, valley residents spent 20 years busily pumping the aquifer beneath them into oblivion before finally tapping Lake Mead in 1971.

The role the lake would play in Southern Nevada’s future was well known long before then. During a speech at the Las Vegas Convention Center on Sept. 28, 1963, President John F. Kennedy said that “supplementary water from Lake Mead — this is what is going to govern the growth of Las Vegas. It’s needed to guarantee the future growth of this city and community.”

Today, 90 percent of the community’s water supply comes from the Colorado River by way of the reservoir formed by Hoover Dam.

“You wouldn’t have been able to sustain any of the growth without the dam,” Kintop said.

And not just here. Hoover Dam is now the linchpin for a tightly managed and regulated river system that sustains billions of dollars in crops and supplies water and power to roughly 40 million people across the Southwest United States and northern Mexico.

Terry Fulp, regional director for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Boulder City, said the dam made Los Angeles and Phoenix grow as surely as it did the winter vegetables in California’s Imperial Valley.

But its impact arguably has been greatest in Southern Nevada, a place with few other options for slaking its thirst.

“I can’t imagine what the Las Vegas Valley would look like if Hoover Dam hadn’t been built. Clearly it would be much different than it is today,” Fulp said.

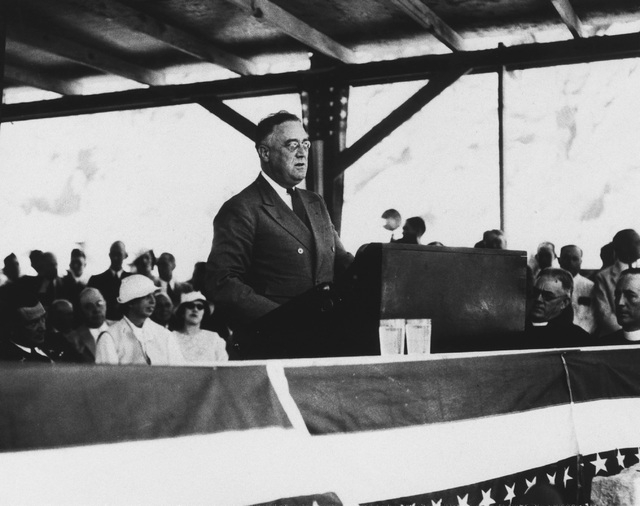

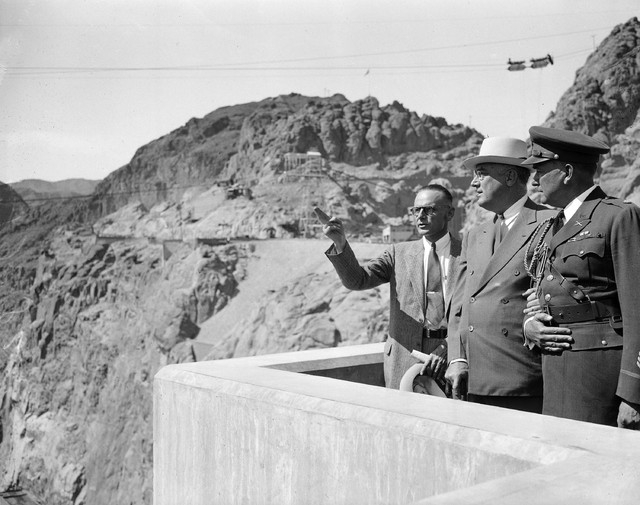

On the day of its dedication on Sept. 30, 1935, Franklin D. Roosevelt, the first American president to visit Las Vegas, stood on the crest of the dam and declared it a “great feat of mankind” destined to reshape “the geography of a whole region.”

Hoover Dam more than lived up to that promise, especially in Nevada, where it first delivered jobs at the height of the Depression and then fueled a growing state with a little water of its own. Simply put, McBride said: “It made Las Vegas the gateway to the American Southwest.”

And it could have delivered even more, had Southern Nevada’s founding fathers been able to see the future.

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Find him on Twitter: @RefriedBrean.