“I do not want to give hepatitis to someone else. I don’t want to make an innocent so sick.”

Rodolfo Meana pulled back his left pant leg to show where a bullet ripped through his thigh.

Not really a surprise, the 73-year-old Meana explained, if you made a career of the military in the Philippines.

When Islamic separatists began fighting for self-determination in the south of the country in the 1970s, Meana said he got in his share of bloody firefights as his government tried to quell the insurgency.

"I could walk for a while after I got shot, but they finally put me on a stretcher and got me on a helicopter so I could go to the hospital," the retired colonel said in halting English last week as he sat in the small Las Vegas apartment he shares with his wife.

Today, Meana has nightmares that awaken him regularly. But they're not the result of years of fighting in the jungle, battles that saw him decorated 18 times for bravery.

What robs him of sleep, makes him pray as he never prayed on the battlefield, is what he fears could happen.

"I do not want to give hepatitis to someone else," he said, his eyes closing behind thick glasses. "I don't want to make an innocent so sick."

Health officials say Meana contracted hepatitis C at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada on Sept. 21; his case was one of a cluster of six traced to that date.

As a result, Meana, who became a U.S. citizen three years ago, no longer kisses his three grandchildren, an 8-year-old boy and two 12-year-old girls.

And no longer will Meana, who has had to tighten his belt two notches because of the weight he's lost since contracting the virus, even think of being sexually intimate with his wife of 43 years, Linda.

"They told me I could use a condom, but I don't want to take a chance. I love her. I will only kiss her on the forehead."

When you are diagnosed with hepatitis C, "your whole life changes."

"You don't want to hurt someone else," said Meana, who uses a handkerchief when turning a doorknob.

Only lately has he felt comfortable shaking hands, which he washes dozens of times a day.

Meana says he has read what the federal Centers for Disease Control has said about how the virus is transmitted: sharing needles to inject drugs; blood transfusions before testing for the virus began in 1992; tattooing with needles that have not been sterilized; sharing razors, toothbrushes, nail clippers and other household items that might have blood on them; and sexual contact.

Repeatedly in literature, the CDC reports that the virus is not spread by sharing eating utensils, hugging, kissing, holding hands, coughing or sneezing.

"I know the experts say it is spread through infected blood," Meana said. "I have read all that. But why should I take a chance that the virus could be spread another way?"

Daniel Carvalho, the attorney representing Meana in a malpractice case against the clinic and its majority owner, Dr. Dipak Desai, has noticed how cautious his client has become.

"There was real hesitancy with that (shaking hands) when I first met him," Carvalho said.

At Desai's clinic on Shadow Lane, authorities investigating a cluster of hepatitis cases had observed clinic nurses reusing syringes in a manner that contaminated vials of medication and, they believe, infected patients. City investigators say that practice was done at the direction of Desai and other administrators.

Meana said he ended up at the clinic at 700 Shadow Lane after complaining to his primary care physician about gas and an acidic taste in his mouth. He said he had an early September consultation with Desai.

On Sept. 21, Meana had his colonoscopy. Neither before nor after the procedure did he see Desai. He said a nurse told him his colonoscopy showed no problems.

In early October, Meana said he started feeling tired "all the time." He could no longer take three- and four-mile walks in the morning, nor could he do the regimen of situps and pushups he had done in the military.

By mid-October he went to his doctor and got a blood test. He didn't get the results until early January.

"I guess it was just because of the holidays that it took so long," he said.

The test showed he had hepatitis C, the virus which attacks the liver and can prove fatal.

"I knew right then I had to have gotten it from the colonoscopy," he said. "I couldn't have gotten it from anywhere else."

But there was no official confirmation at the time.

His family physician sent him back to Shadow Lane for treatment. Meana didn't get the treatment, however.

The clinic had been shut down by authorities after health officials began an investigation in January. Forty-thousand former patients of the Shadow Lane facility were urged to get tested for hepatitis and HIV.

Meana became so weak with hepatitis during the winter that he came down with pneumonia. Another doctor said he was too old for interferon treatments, which helps the immune system defend against hepatitis. Like chemotherapy for cancer, interferon can be very taxing on a patient.

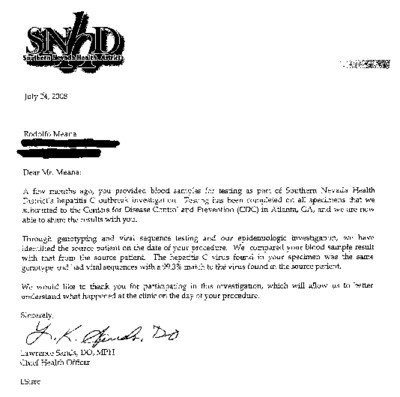

In July, Meana received a letter from the Southern Nevada Health District. There now was no doubt where he contracted hepatitis C.

The letter from Dr. Lawrence Sands said his hepatitis case was genetically linked to the district's hepatitis investigation.

"The hepatitis C virus found in your specimen was the same genotype and had viral sequences with a 99.3 percent match to the virus found in the source patient," the letter read.

"I guess it was good to know," Meana said.

Meana said he has never acted out in anger about what has happened.

"You have to remember that I was in the military," he said. "I have been trained to handle bad things that happen to me."

He has battled frequent bouts of diarrhea, fever and nausea, accompanied by debilitating fatigue.

He does admit to depression, from constantly worrying about hurting others with the virus that eats away at him.

But the retired professional soldier, who came to the United States in 1997 to join two of his married daughters and his grandchildren, said he still believes he made the right decision to move.

"I love the United States, being close to my grandchildren," he said, smiling. "I came here partly because it is the safest country in the world. Sometimes, though, I've learned even the safest country may be safe from war, but not other things."

The colonel has decided that he loves life too much to just wait for hepatitis to kill him.

He has found a new doctor that will give him the interferon treatment. Tests on his liver show problems that may be able to be corrected with the treatment, he said. But for now, his doctor is just monitoring his immune system, taking him off all drugs other than his medicine for hypertension.

"If the interferon is too much for me, I will go off of it," he said.

At night, when Meana cannot sleep, he sometimes sees the face of Desai in his mind's eye.

"I don't like seeing the man who made it so I can't kiss my grandchildren," Meana said. "I must say that it makes me angry."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.