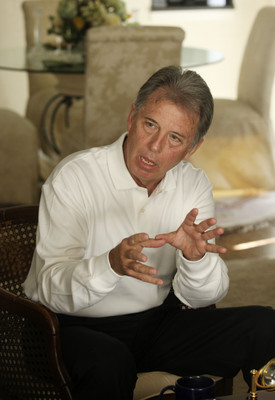

Making his case for justice

Tasked several years ago with writing a unanimous Nevada Supreme Court decision, William Maupin, as had been his custom for years, took a last look at the case before trying out opinions from both points of view.

The experiment changed his mind -- and everyone else's on the court. The final vote was 7-0 in the other direction.

The recently retired Maupin's work on that case typified a workmanlike and academic approach to the law that made him what former Justice Robert Rose calls the "intellectual anchor" of the Supreme Court.

"He really wanted to get the right result," said Rose, who served with Maupin from 1997 to 2006. "He would immerse himself in cases as much as any judge I've ever seen."

Case by case and, later, issue by issue, Maupin had a major impact on the Nevada legal system during his 12 years in Carson City, according to lawyers, legislators, and fellow judges who observed his work.

"He brought a new level of scholarship to the Supreme Court," said Washoe County District Judge Brent Adams. "In addition to being a fabulous appellate judge, he implemented concrete rules that have improved our legal system."

The often-heard sentiment that Maupin's absence will be felt on the Supreme Court is rooted in a sober fact: Maupin was the last of a group of justices including Rose, Miriam Shearing and Cliff Young who are credited with bringing the Supreme Court out of an era of turmoil in the 1990s.

Justice Mark Gibbons, re-elected to a second term on the high court last year, is now Nevada's longest-serving justice.

Maupin, now 62 years old, was a popular justice from the time he joined the then five-member Supreme Court in 1997, bringing with him 26 years of legal experience, including work as a public defender, civil litigator and Clark County district judge.

Shortly after he announced his retirement last year, 84 percent of respondents in the Review-Journal's biennial Judging the Judges survey recommended he be retained if he ran for re-election to the Supreme Court.

The score was consistent with Maupin's past ratings, which never dipped below 83 percent during his time on the state's high court.

As his approval ratings stayed constant, Maupin's conception of the law evolved.

"I think I realized how relatively helpless people are who need access to the court system, when they approach this monolith that is our legal system," he said. "The government may be trying to take your liberty, to take your property, and the legal system is there to make sure that, if it does happen, it happens in accordance with due process."

During a second stint as chief justice in 2007, Maupin embarked on an ambitious set of public-policy reforms that cut to the very core of how he now views the justice system.

Taking a page from Rose, who in 2006 established a commission to study the state of the Nevada judiciary, Maupin impaneled two commissions: the Commission on Preservation, Access, and Sealing of Court Records and the Commission on Indigent Defense. In doing so, the self-described "lawyer's lawyer" and "legal wonk" added another label: issues-driven chief justice.

The commissions were formed after two Review-Journal series raised questions about the court system's policies for sealing records and for providing legal counsel to poor defendants.

Both of Maupin's commissions made recommendations that led to new Supreme Court rules binding throughout the Nevada courts.

As a result, civil court records are now more open to the public, and the state's public defender systems are closer to compliance with American Bar Association standards.

Maupin called the study of indigent defense "the most important examination of the criminal justice system" in Nevada in recent years.

Washoe County's Adams, who chaired the sealed records commission, said Maupin was especially outraged by the practice of "super sealing" cases, which made the very existence of some cases unknown to the public.

Federal Public Defender Franny Forsman, a member of the indigent-defense commission, said Maupin's efforts to improve public defender systems stemmed from his belief that people should be equal in the eyes of the law.

"He had a sense of fairness, especially when he saw any kind of imbalance in the justice system," said Forsman, who has known Maupin since their college days together in Reno in the late 1960s. "He was willing to take risks in order to change things."

Maupin also understood that the judiciary couldn't go it alone when it sought change, said Assembly Judiciary Chairman Bernie Anderson, a Democrat from Sparks.

Anderson said Maupin set a high standard for the relationship between the judicial and legislative branches of government.

"He recognized the political reality of what could and couldn't be done," Anderson said.

In 2007, Maupin pushed for and got authorization for new judges and a judicial pay increase. His advocacy also helped advance proposed constitutional amendments that would create an intermediate appeals court and an appointment system for judges.

An appellate court is at the top of Maupin's list of unfinished business.

The proposal has surfaced several times in the Legislature over the past 30 years, and it made it to the ballot in 1980 and 1992, only to be rejected by voters both times.

Another attempt at the measure cleared the Legislature in 2007. It must pass the 2009 Legislature and a vote of the people in 2010.

"It's failed twice, but it hasn't been well-promoted," Maupin said.

Though he identified several aspects of the courts that needed reform, Maupin is a strong defender of the system as a whole, especially the integrity of its presiding judges.

The conduct of some judges has been called into question over the years, most comprehensively in a series of stories by the Los Angeles Times in 2006 about conflicts of interest among Nevada jurists.

"The proposition that justice is for sale in Nevada is the biggest bunch of hogwash I've ever heard," Maupin said.

But he said he understands why that viewpoint has gained traction: "The perception comes from judges having to run in general popular elections and having to raise campaign funds, which creates appearances we'd rather not create."

Maupin hasn't been immune from involvement in the debate over campaign contributions. Like many Nevada jurists, he took campaign contributions from attorneys who appeared before him.

To address the perception that money influences justice, Maupin said he would like to see Nevada change its system of electing judges.

"Philosophically, I think judges should be appointed," he said.

Maupin worked to make the existing system more transparent.

As chief justice in 2007, he successfully urged the Supreme Court's Commission on Judicial Selection to hold open hearings for lawyers seeking to fill vacant District Court judgeships and Supreme Court justice positions.

In retirement, Maupin is going back to a legal area where he made an early and lasting mark.

As a Clark County district judge in 1992, he chaired a Supreme Court committee that devised the judicial system's arbitration program, which allows litigants to avoid full-blown jury trials and helps judges reduce the number of cases on their dockets.

Maupin plans to start a mediation and arbitration firm with Gene Porter, a former district judge and former Assembly majority leader.

Maupin declined an invitation to serve as a senior judge or justice, but he's keeping an open mind about a wide range of other options.

"I'm certainly interested in the political process, whether it be in a consultive capacity for people running judicial campaigns or nonjudicial campaigns, or ultimately even being a candidate," said Maupin, who is a registered Democrat. "All of those things are on the table."

For now, he is happy to reflect on his years on the Supreme Court, a 12-year journey that led him to a less clinical and more compassionate view of what the legal system is all about.

Maupin said he would like to be remembered as "a judge who loved the law because, in truth, law is all about people."

Contact reporter Alan Maimon at amaimon @review journal.com or 702-383-0404.

Hear retired Nevada Supreme Court Chief Justice William Maupin's thoughts on a number of legal topics Clip 1 Clip 2