Witness says Freddie Gray tried to injure himself in Baltimore police van

Freddie Gray, whose death after being injured in Baltimore police custody sparked rioting in the city, was “banging against the walls” of a police van and “was intentionally trying to injure himself,” a prisoner being transported with Gray has said, the Washington Post reported on Wednesday.

The prisoner’s account was contained in an application for a search warrant that was sealed by the court, the Post said. The prisoner, who is currently in jail, was separated from Gray by a metal partition and could not see him, the paper said.

Gray, 25, was found unconscious in the van when it arrived at a police station on April 12. He had suffered a spinal injury and died a week later.

The Post said the affidavit was part of a search warrant seeking the seizure of the uniform worn by one of the officers involved in the arrest or transportation of Gray.

BALTIMORE MOM WHO SMACKED SON AT RIOT: ‘I DON’T PLAY’

You know the Baltimore mom who went to the riot, found her son and lit into him with her right hand? Well, Toya Graham said Tuesday she did it because she didn’t want her son to become another Freddie Gray.

She also told CBS News that she’s a single mother of six who doesn’t play when it comes to her children.

In video captured Monday by CNN affiliate WMAR, Graham is seen pulling her masked son away from a protest crowd, smacking him in the head repeatedly, and screaming at him.

Graham told CBS News that her son said he wanted to run when he saw her coming.

“I’m a no-tolerant mother. Everybody who knows me, knows I don’t play that,” Graham told the network. “He knew. He knew he was in trouble.”

Graham told CBS News that she and her son made eye contact and she didn’t even think about the news cameras when she went after her boy.

“That’s my only son and at the end of the day I don’t want him to be a Freddie Gray,” she told CBS. “I was angry. I was shocked, because you never want to see your child out there doing that.”

On the video the boy — dressed in dark pants and a black hoodie — tries to walk away, she follows him, screaming, “Get the f—- over here!”

Eventually, he turns toward her, his face no longer covered.

Graham said when she arrived at Mondawmin Mall, she saw people throwing objects at police. She said what she saw could not be called protesters out for justice.

Tameka Brown, one of Graham’s five daughters, told CNN on Tuesday it wasn’t that hard for her mom to spot her 16-year-old brother.

“She knows her son and picked him out. Even with the mask on, she knew,” Brown said.

Her brother is actually grateful that his mom came to get him, she said. He understands Graham did it because she wants to keep her son alive.

“She has always been tough and knows where we are at,” Brown said.

Police Commissioner Anthony Batts thanked her in remarks to the media on Monday night.

“And if you saw in one scene you had one mother who grabbed their child who had a hood on his head and she started smacking him on the head because she was so embarrassed,” he said. “I wish I had more parents that took charge of their kids out there tonight.”

Graham told CBS that at times she tells her son to stay inside.

“There are some days I’ll shield him in the house just so he won’t go outside. And I know I can’t do that for the rest of my life. He’s 16 years old, you know,” she said.

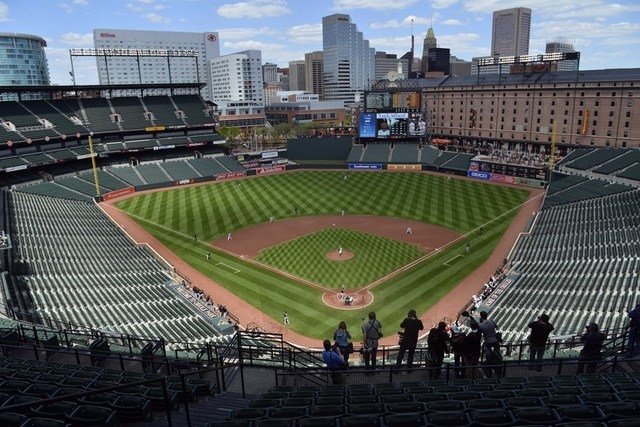

CAN BASEBALL BRING A CITY TOGETHER?

It seems almost silly to be writing about baseball in the context of recent events. Except it isn’t.

Last weekend, as Baltimore reacted to the death of Freddie Gray, the young man who died last week from a spinal cord injury he suffered while in police custody, Major League Baseball had a problem on its hands. Saturday’s game between the Orioles and Red Sox had gone into extra innings in Camden Yards, with plenty of fans for both teams glued to their seats.

Boston fans feel at home in Oriole Park — a so-called retro urban park built to embrace the luxuries of modern stadiums while maintaining that nostalgic feel — because much of it was based on Boston’s Fenway Park. The Boston faithful are used to being in the heart of a city to watch sports. But when the Orioles finally pulled out a win in the 10th inning, 36,000 fans remained in their seats. They had been asked to do so by Baltimore officials due to “ongoing public safety issues.”

The riots of Baltimore, the peaceful marches of Baltimore, the fury and unrest of Baltimore did not seem to have had much to do with baseball. But as the always-wise Atlantic magazine writer (and Baltimore native) Ta-Nehisi Coates’ take on the situation quickly went viral, it became clear that the Oriole’s home stand presented a problem.

Monday’s game against the Chicago White Sox: postponed less than an hour before the first pitch.

Tuesday’s game against the White Sox: also postponed.

Such action by MLB is not without precedent. In 1967 in Detroit, the 12th Street riots forced the Tigers to postpone one game and relocate others (to Baltimore, no less). After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., MLB postponed opening day games out of fear of mob violence. In the wake of the 1992 verdict in the Rodney King beating, the Los Angeles Dodgers postponed several games. The entire league went on hiatus in the wake of the terrorism and violence of September 11, 2001.

Politics threaten sports all the time. From the demonstrations against the Brazilian government before last summer’s World Cup to the massacre of protesting students days before the Opening Ceremony of the Mexico City Olympics in 1968, sports knows well that it sits within the larger context of the world.

Our deep investment in our teams — beyond the tax dollars that construct the stadiums and the salaries players make (and the profits the owners and sponsors draw) — is supposed to work to create community, to unify. Cheering for the home team is supposed to create a sense of belonging.

“It’s interesting that I have not yet heard anyone say that baseball or sport can heal this wound,” Daniel Nathan, professor of American Studies at Skidmore College and editor of “Rooting for the Home Team: Sport, Community and Identity” told me. “People did say that in the weeks after 9/11. This is not 9/11 — not even close. But it is a serious social and cultural rupture. Painful.”

What happens next is striking. After two postponements, the Orioles will play Chicago on Wednesday, but no one else will be invited. In an unprecedented move by major league baseball, the public is not invited to the final game of the series, moved to the afternoon in accordance with the curfew imposed by Baltimore’s mayor.

While there are a few examples of fan-less games being played in the United States, none have been for such reasons, while in Europe, there have been a handful of incidents in which soccer teams have been punished for fan behavior with fan-less games.

Without fans, does baseball mean anything?

When the new Camden Yards made its debut in 1992, people heralded the return of the old-time stadium smack in the middle of the city. But are the residents of that city ready to reminisce about the so-called good old days?

In a recent episode of “Real Sports,” Chris Rock delivered a brilliant seven-minute diatribe on the fact that less than 10% of baseball players or fans are black.

“Last year, the San Francisco Giants won it all without any black guys on the team,” he said. “The team the Giants had to beat to get there, the St. Louis Cardinals, had no black people. None. How could you ever be in St. Louis and see no black people?”

Rock’s thesis? That baseball’s sense of nostalgia encompassed by places like Camden Yards does not sit well with African Americans, whose memories of the old days are anything but good.

To his credit, Orioles Executive Vice President John Angelos, son of majority owner Peter Angelos, took to Twitter to prioritize the issues at hand, focusing not on the lost games, but on the “unfairly impoverished population living under an ever-declining standard of living and suffering at the butt end of an ever-more militarized and aggressive surveillance state.”

Yet as much of America continues to grapple with the idea that black lives matter, it is clear that the country believes sports do matter, whether or not anyone is there to watch.

And with MLB’s announcement that Baltimore’s weekend games will be moved to Tampa, it becomes clear that the only thing that the United States has figured out about race relations, poverty, the achievement gap, police brutality, and so on is how to keep its baseball players safe and make sure that the games go on.

WHAT’S NEXT IN FREDDIE GRAY INVESTIGATION?

Perhaps lost amid the chaos that has descended on Baltimore is that two investigations are seeking to determine how Freddie Gray suffered a fatal spine injury in police custody.

A scroll through the reports out of the Baltimore Police Department Twitter feed since Gray’s death offers a tour of the mayhem the city has experience — looting, vandalism, blazes, attacks on police and firefighters, marauding “criminals” stoking the havoc.

Talk of the violence has overtaken, or at least outweighed, updates about the investigation.

The investigation is scheduled to be completed Friday, at which point, it will be handed over to a prosecutor who will decide whether to file charges in the case.

“Let me further clear up: When we take our information or our files to the State’s Attorney’s Office on Friday, that is not the conclusion of this investigation,” Police Commissioner Anthony Batts said last week. “That is just us sitting down, providing all the data we have. We will continue to follow the evidence wherever it goes.”

As for the federal investigation into whether Gray’s death was the result of a prosecutable civil rights violation, newly appointed Attorney General Loretta Lynch said Monday that the Justice Department’s civil rights division and the FBI “will continue our careful and deliberate examination of the facts in the coming days and weeks.”

Because of the Baltimore Police Department’s history, the Justice Department has been working with the police force since October as part of a reform initiative that will assess “policies, training and operations as they relate to use of force and interactions with citizens.”

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake requested that the Justice Department to take a look at the Police Department, The Baltimore Sun reported, saying that her request came on the heels of the newspaper’s report that the city had paid almost $6 million in judgments and settlements in 102 police misconduct civil suits since 2011. Overwhelmingly, The Sun reported, the people involved in the incidents that sparked the lawsuits were cleared of criminal charges.

City officials have promised answers and accountability in Gray’s death.

“We welcome outside review,” police spokesman Capt. Eric Kowalczyk has said. “We want to be open. We want to be transparent. We owe it to the city, and we owe it to the Gray family to find out exactly what happened.”

Added Rawlings-Blake, “We will get to the bottom of it, and we will go where the facts lead us. … We will hold people accountable if we find there was wrongdoing.”

According to police, officers encountered Gray on April 12 and he “fled unprovoked.” Three officers gave chase, apprehended Gray and carried him — screaming, his legs dangling listlessly — to a police transport van. Once at the police station, officers requested an ambulance, which took Gray to the University of Maryland’s Shock Trauma Center, where he died a week later.

An autopsy report indicated Gray died of a spinal injury, but Batts said Friday that the medical examiner was still awaiting a toxicology report and a spinal expert’s analysis before issuing his final report.

So far, six officers involved in the arrest have been suspended with pay: Sgt. Alicia White, 30; Officer William Porter, 25; Officer Garrett Miller, 26; Officer Edward Nero, 29; Lt. Brian Rice, 41; and Officer Caesar Goodson, 45.

Releasing the officers’ names is standard procedure after an in-custody death and in no way implicates wrongdoing, Kowalczyk said.

Though the investigation is not yet complete, Batts said Friday that there are at least two indications that officers involved in Gray’s arrest did not follow protocol.

“We know he was not buckled in the transport wagon, as he should’ve been. No excuses for that, period,” he said. “We know our police employees failed to get him medical attention in a timely manner multiple times.”

That Gray wasn’t buckled has raised speculation that he was injured during what’s known as a “rough ride” or “nickel ride,” in which officers place a handcuffed suspect in a police van and drive recklessly so as to toss the suspect around.

Asked whether Gray could have incurred his injuries via a rough ride or outside of the van, Batts said there is “potential” that both could be true.

The Baltimore Police Department has established a task force composed of 30 investigators — including members of the force investigation unit and homicide detectives — to look into Gray’s death, Batts said.

They’ve conducted dozens of interviews, canvassed the region on foot seeking witnesses and procured video from several closed-circuit television cameras around the city.

Deputy Commissioner Kevin Davis, who is overseeing the task force as the head of the Investigations and Intelligence Bureau, said Friday that the evidence shows Rice and two other officers on bikes were the first to see Gray. Two officers remained on their bikes and one gave chase on foot, pursuing Gray for about one-fifth of a mile.

“That’s where the apprehension of Freddie Gray occurred, and quite frankly, that’s exactly where Freddie Gray should have have received medical attention, and he did not,” Davis said Friday.

The paddy wagon carrying Gray traveled about one block before stopping, and Gray was removed from the van and placed in leg irons, Davis said. It then traveled about 1.3 miles before stopping again “to deal with Mr. Gray, and the facts of that interaction are under investigation,” he said.

It was at that stop, Batts added, that officers picked Gray off the floor and placed him on a seat in the transport van. Gray requested a medic during that stop, he said.

The van then traveled to another incident, about a mile away and just a few hundred feet from where Gray was first spotted and chased. There, a second prisoner was placed in the van, which headed back to the police department’s Western District building, about four-fifths of a mile away, the deputy commissioner said.

It was only then that an ambulance was called and Gray was taken to the University of Maryland’s Shock Trauma Center.

“It’s complex,” Davis said of the probe. “It involves a minutiae of details. It requires our full talents, our full time, and we’re going to get this right.”

While Batts told reporters that “the picture is getting sharper and sharper as we move forward,” he said there is still a gap between where officers first chased Gray and where bystander video captures the officers mid-arrest before carrying him to the van.

“He’s able to talk. He’s able to move. He’s able to stand on his left foot. I’m told he’s able to enter the van at that point in time,” he said.

Every stage of Gray’s transport is being investigated, Davis said, but the details are not yet clear enough to share with the public at the moment.

Batts elaborated: “What you see us tap dancing on and balancing here is that if someone harmed Freddie Gray, we’re going to have to prosecute them.”

Giving out too much information now, he said, could endanger the prosecution.

RELATED

Here’s what you need to know about the Baltimore riots — VIDEOS

Man dies after neck partially severed in police custody

Baltimore man’s death week after arrest being questioned