Nevada desert provides answers

Nevada has a bright spot in the high desert and it's not another solar energy project.

Instead, it's a place to explore the solar system as well as probe suspect gases that scientists believe are causing climate change.

It's a place where scientists flock to calibrate their tools for tracking Earth's greenhouse gases and help them in their search for life on Mars.

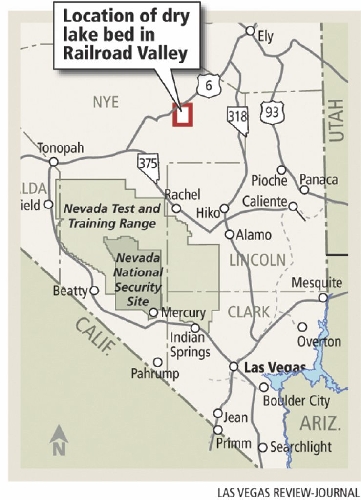

The sun-baked dry lake bed, or playa, in Railroad Valley, 75 miles southwest of Ely, is an ideal place to do this.

Its shiny, reflective surface and bare surroundings make it easy to spot by cameras on satellites.

And, there are no coal-fired power plants belching carbon dioxide. Nor are there any active volcanoes spewing amounts of greenhouse gases that would dwarf emissions from any single power plant that burns fossil fuels.

Aside from the spectrum of gaseous compounds that makes up the atmosphere, only the slight burp of methane -- such as that sucked up by a syringe stuck into the lake bed's cracked mud -- is there for measuring and comparing with what might be evidence of life on Mars.

Is there evidence of life in the form of microbes, akin to those in Railroad Valley, might exist on Mars?

"There is no way to tell," said Brad Bebout, a space science researcher for NASA Ames Research Center who hopes his work someday will answer that question.

"It's entirely possible there is life on Mars somewhere. If there is life it has to be underground," said Bebout, who began his quest years ago as a graduate from the University of Nevada, Reno.

By studying chemical signatures from places where methane is emitted into the atmosphere, scientists can tell if methane gas was produced by salt-loving organisms, called "halophiles," or stems from a nonliving source, like heating up petroleum that also lies beneath the lake bed but much deeper.

The single-celled organisms can multiply rapidly under the right conditions and give off enough "biogenic," or life-produced methane to distinguish it from the "thermogenic," or heat-produced methane that contains a heavier type of carbon.

Bebout noted that after years of research "it seems pretty clear that there were places where there was salty water on Mars," similar to Railroad Valley.

For a few days in June, a team of scientists collaborating with Bebout and colleague Chris McKay poked stainless steel tubes into the dry lake bed and flew an instrument-laden drone aircraft over it.

A jet, dubbed Alpha, from NASA Ames at Moffett Field, Calif., also soared overhead and spiraled down from 25,000 feet with sensors to capture a vertical profile of the air over Railroad Valley.

The data will be used to calibrate instruments on the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, destined for a 2016 mission to the red planet, and another satellite that will be launched sooner for carbon dioxide observations over Earth.

"It's a great place to go calibrating. It's big and flat and boring, which is perfect," said Earth science researcher Laura Iraci, from NASA Ames' Atmospheric Science Branch.

Japan's GOSAT -- Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite -- even joined in the campaign for 10 days in June to use the Railroad Valley salt flat to calibrate space-based observation of carbon dioxide and methane.

From a few feet below ground to the rim of GOSAT's orbit high above Earth, the data collected will tell scientists what adjustments to make when NASA launches its Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 mission in February 2013.

The satellite's instruments will "see" and measure photons -- reflected sunlight that strikes Earth and bounces back to the satellite. Molecules of carbon dioxide absorb a certain wavelength of light. When the satellite detects those wavelengths are missing, scientists can tell automatically how many carbon dioxide or methane molecules are in the atmosphere.

Preliminary results from the calibration campaign look good, she said. The next step is to translate that to what the satellite will "see."

While carbon dioxide is being measured at stationary locations around the planet to assess its contributions to global warming, "the satellite will see the whole globe. Right now there are a lot of places, such as over the ocean, where you can't really "see" emissions, she said.

And that might reveal some clues about global warming.

Her comments Friday coincided with a new report in the journal Science about the decline of large animals in all regions of the world that is causing "substantial changes to Earth's terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems." This includes the demise of great whales that consumed plankton , that are now releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere .

"The result has been the transfer of approximately 105 million tons of carbon into the atmosphere that would have been absorbed by whales, contributing to climate change."

The work at Railroad Valley by scientists from NASA Ames and colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory stands to bridge the gap of knowledge about the oceans' role in greenhouse gas emissions.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.