Rapid roars as the Colorado sets new course

The falling water level has chased marinas from their shrinking harbors and left boat ramps high and dry. Now the drought has spawned an unexpected new problem at Lake Mead: rapids.

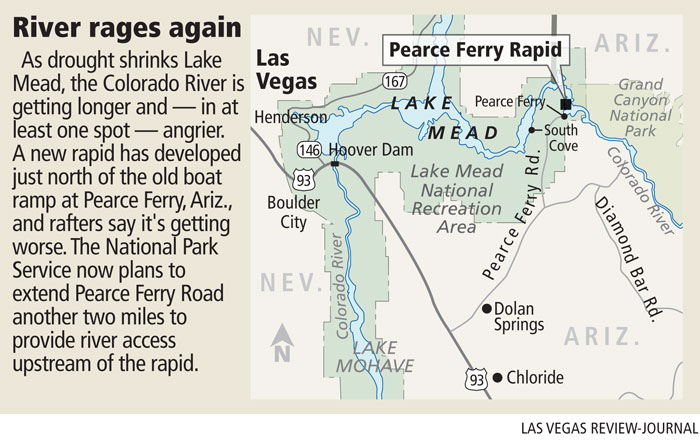

At the massive reservoir's eastern-most edge, 120 miles from Las Vegas, a small but dangerous new pocket of white water has roared to life where a tranquil finger of flat water used to be.

The so-called Pearce Ferry Rapid features a sharp drop and a hard right turn, as the Colorado River tumbles around a rock outcrop, down a once-buried ridge and straight into a hillside.

One rafting Web site describes it as a Class 4 rapid on the 1-to-6 scale, with such perilous-sounding features as a "sharp reverse-current hydraulic," a "pour-over," a "fast channel" and a "chaotic eddy."

And experts agree the riffle is getting rougher.

"This thing has worsened significantly over the last year and a half," said Jim Holland, park planner for the Lake Mead National Recreation Area. "It's become much more dramatic."

It's also developed in reverse, getting worse as the flow of the river declines and the lake recedes.

Since drought took hold on the Colorado River in 2000, the water level at Lake Mead has fallen more than 100 vertical feet. The drop has left the Colorado to reclaim dozens of miles of terrain in northwestern Arizona where the recreation area meets Grand Canyon National Park.

"It wasn't even a river there. It was a lake," said Mark Grisham, executive director of the Grand Canyon River Outfitters Association.

But instead of obediently returning to its historic channel, the river has carved a new course through the thick layer of silt that began collecting when Hoover Dam was finished in 1935. Just downstream from the old Pearce Ferry boat ramp, that new channel "runs right smack into a wall and turns," Grisham said.

Holland acknowledged that this is not the sort of problem National Park Service personnel at Lake Mead are used to dealing with.

"There is an irony there that these flat-water guys are now dealing with white-water issues," he said.

Of course, the new riffle doesn't compare with the serious Grand Canyon white water that precedes it, but Pearce Ferry Rapid is causing headaches for commercial river rafters whose trips through Grand Canyon end at the lake.

"It's a pretty unusual situation. It's not every day you see a new rapid develop on a river," Grisham said. "From a geologic perspective it's pretty interesting. From an operational standpoint it's a real problem."

The park service closed the boat ramp at Pearce Ferry in 2002 because of the falling water level. Since then, commercial raft trips have been forced to motor an extra 15 miles to the take-out at Lake Mead's South Cove.

Grisham said South Cove is now the end of the line for more than half of the 18,500 people who take commercial raft trips through the Grand Canyon each year.

And while river rafts can still negotiate Pearce Ferry Rapid without too much trouble, the white water has made upstream travel in most hard-hulled boats all but impossible.

As a result, rafting companies no longer can use jet boats to unload customers early and spare them a slow, hot float across Lake Mead after an exciting, white-water plunge through the Grand Canyon.

"It's just a bad way to end the trip," Grisham said.

In hopes of addressing the problem, the park service is teaming up with rafting companies and the Hualapai Indian Tribe to build a two-mile dirt road that will restore access to the river at Pearce Ferry, just upstream from the rapid.

The tribe is involved because it offers rafting adventures as part of its Grand Canyon West tourism venture, which also includes the glass-bottomed Skywalk extending 70 feet out over the canyon's West Rim.

"The (rafting) industry and the tribe have always wanted to maintain operations at Pearce Ferry," Grisham said.

The park service considered building the road a few years ago but rejected the idea because it was complicated, expensive and destined to wind up at the bottom of the lake once the water came back up.

About six months ago, commercial rafters and tribal representatives persuaded the park service to reconsider, even offering to build the road themselves if necessary, Holland said.

To show they were serious, the companies and the tribe hired an engineering firm to draw up the plans.

Construction of the road is expected to take four to six weeks and cost $770,000. The park service probably will pick up the tab, but a take-out fee for boats at Pearce Ferry is being considered to help with upkeep of the road.

If everything goes exactly as planned, Holland said, the work could begin by the end of May, and the road could be open in early July.

"But there's a lot of things that have to fall into place for that happen," he said.

Grisham and the rafting companies he represents hope to see the new Pearce Ferry take-out open as soon as possible because the rafting season runs from April to October and peaks from now to mid-September.

For the moment, commercial raft pilots are running the new rapid and then offloading their passengers onto jet boats just downstream and racing them to South Cove.

Grisham said the new procedure, which adds five to seven hours to each Grand Canyon trip, might not work for long. Some have speculated that Pearce Ferry Rapid is on its way to becoming a "cascading waterfall," which would prevent even rafting boats from safely navigating through the area, he said.

But not everyone supports the road project.

Tom Martin is co-director of River Runners For Wilderness, an organization dedicated to protecting the Colorado River watershed and the rights of recreational boaters.

He said he likes the idea of improved public access to the new rapid and the Pearce Ferry area as a whole, but the road seems like a waste of money. Either it will be washed away when the lake level goes back up, or another rapid will develop upstream, prompting the rafting companies to demand another new access point, he said.

Martin would prefer to see raft companies lose the jet boats and use the extra time on the river to show their passengers the true impacts of drought and water management in the Southwest.

Right now, he said, the Colorado River is behaving like "a hose flailing around on the front lawn." The cause is human development of a once-wild river system; the result is Pearce Ferry Rapid.

"That's a huge teachable moment for a whole bunch of commercial (rafting) customers," Martin said, but the lesson is getting lost in the roar of jet boats, helicopters and other things meant to make the river-running experience more "convenient."

"(It) strips out the wilderness component from Grand Canyon," he said. "Wilderness is not about convenience."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.