SHINING STAR AT UNLV

Bing Zhang used to be jolted awake at all hours of the night by events millions of light years away.

A pager would go off, and he would roll out of bed and log onto his computer.

Waiting for him would be spectacular images and data captured of the most powerful explosions in the universe: gamma-ray bursts, or GRBs.

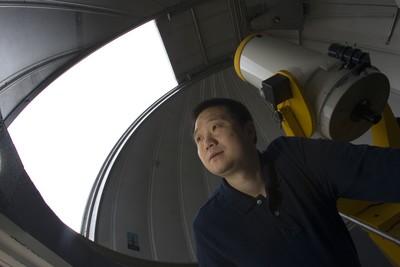

As part of a NASA team studying the mysterious explosions, Zhang, 38, an astrophysicist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is at the forefront of GRB research.

He and the NASA "Swift" team, named for the satellite that tracks the explosions, which usually last only a few seconds, have discovered GRBs so distant that astronomers have had to reevaluate the size of the universe.

"These are the brightest, wildest explosions in the universe," Zhang said.

Gamma-ray bursts are believed to occur when massive stars explode or when a black hole swallows a neutron star, an event that occurs somewhere in the universe two or three times per week.

The energy generated during the events is greater than that of a billion suns, scientists believe.

Zhang was a lead author on a GRB paper that Science magazine declared the fourth most significant breakthrough of 2005.

He also published a paper in December that redefined how the explosions are categorized.

Attracting him to UNLV, after stints at NASA and Penn State University, was a major coup, said Ron Yasbin, dean of the university's College of Sciences.

"He's a machine," Yasbin said. "We're not sure quite how he has a family life."

His hire helped the university attract two other key faculty members.

"When we got Bing to come, then we started getting applications that were incredible for the next two positions," Yasbin said.

Since joining UNLV nearly three years ago, Zhang has also attracted grants from NASA worth $750,000.

He's also working with a massive telescope in Utah to record GRBs at ground level.

Since NASA's Swift satellite was launched in 2004, scientists have made huge advances in gamma-ray burst research. The satellite captures images and calculates the size and intensity of the explosions.

But little is known about what causes the explosions, and what material is discharged during the explosions.

"That is long-debated," Zhang said. "The traditional view is that it's just normal matter (that is discharged); it's just plasma, electrons and protons. But there is evidence suggesting that magnetic fields are also very strong in the region."

Because most gamma-ray bursts are caused by the explosion of relatively young stars, there are fewer and fewer explosions occurring as the universe ages.

The Milky Way is a relatively old galaxy. As a result, Zhang said, there is little chance a gamma-ray burst could occur near Earth.

The nearest recorded GRB was 10 million light years away, he said.

If one did occur, the effects would be disastrous, burning through the Earth's ozone layer and letting in deadly levels of ultraviolet light from the sun, he said.

"It's not the gamma ray that would kill humans, but the sunlight, or ultraviolet light, that would kill humans," Zhang said. "That is the imagination, but in reality, there is a very low chance for that to happen."

Zhang is now setting his sights on writing three papers based on GRB data that has been analyzed using a software program developed by several of his graduate students at UNLV.

"Astronomy is something that you cannot apply directly to our daily life, but just to satisfy this human curiosity of thousands of years, of how planets were formed, how the stars form and die," he said. "GRBs are actually the great link to understanding all these things."