Water standoff between Nevada, Utah puts rancher in tough position

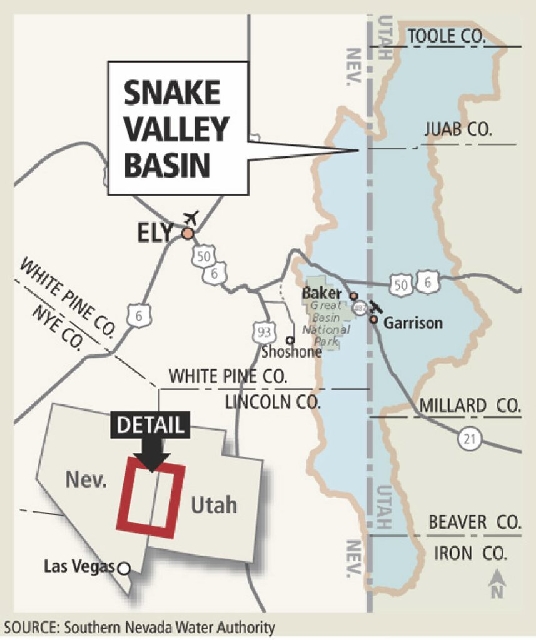

In Snake Valley, the sun comes up in Utah and sets in Nevada.

The man in the middle has worked both sides of the line for more than 50 years.

Dean Baker moved to the valley 300 miles northeast of Las Vegas in 1959 to help run a ranch his father took on there a few years earlier.

The only town on the Nevada side already was called Baker when Dean and his dad got there, but it might as well be named for them.

By most accounts, Dean Baker and his three sons now control more private land and use more water than anyone else in Snake Valley.

Baker lives in Nevada, about three miles west of the border, but his ranching operations and his loyalties spill into Utah.

When the two states quietly launched talks almost a decade ago on how to share the valley’s water, Baker served on Utah’s negotiating team.

When Gov. Gary Herbert announced last month that Utah would not sign the finished agreement with Nevada, it set the stage for a cross-border fight over who controls water and where it should be allowed to go.

And there, smack in between, is Dean Baker.

LOSING HIS VOICE

The man in the middle can feel his mind slipping.

Alzheimer’s, he thinks. He’s been traveling to St. George, Utah, for tests.

Baker beat cancer eight years ago, but he is afraid he won’t beat this, not forever. He already is handing off control of the ranch and other assets to his family to make things easier if his health deteriorates.

Sometimes he can’t recall the names of people he has known forever. Or he hears names but can’t connect them in his head to the people they belong to.

It’s strange, the 73-year-old says. “I remember less and talk more.”

But some things come back to him just fine. Oct. 17, 1989, for instance. That’s when Las Vegas water officials launched a sweeping grab for unappropriated groundwater across rural Nevada, including Snake Valley.

“There are some things I still remember a lot. The Southern Nevada Water Authority thing I still remember,” he says.

Baker has spent much of the last 20 years attending meetings, writing letters, serving on committees and joining lawsuits in hopes of blocking the authority’s multibillion-dollar pipeline proposal.

He even registered as a lobbyist during the last two Nevada legislative sessions, though he hasn’t made as many trips to Carson City this time around.

Baker says he only went two or three times early in the session, mostly to hand out copies of a short DVD about Snake Valley to as many lawmakers as he could.

“It was only to fight Southern Nevada Water.”

Baker has been fighting that fight so long now that he has become the face of the opposition, his words and picture carried on the network news and in newspapers across the United States and Europe. Many of the stories cast him as a folk hero, the humble rancher fighting to protect his spread from the insatiable thirst of Sin City.

But Baker insists he is not just looking out for himself. He is convinced the pipeline would be a disaster for everyone — ranchers, wildlife, ratepayers in Las Vegas, everyone. Billions of dollars, wasted on nothing.

“It will be such a big disaster to Las Vegas that it will be a disaster to the whole state,” he says.

What the authority wants simply isn’t there, certainly not in Snake Valley, Baker says. If it ever was, people like him pumped it from the ground long ago.

“Baker Ranch has killed at least a half dozen springs, and others have killed springs too,” the Utah native says. “It’s perfectly clear now that we’re mining water, and we really need to shut some of our pumps down.”

WRESTLING OVER WATER

When the man in the middle joined Utah’s negotiating team, Southern Nevada Water Authority officials were surprised and a little concerned. After all, what chance was there for a reasonable deal in Snake Valley with one of the authority’s biggest foes in the room?

But emotion and rhetoric never played a role in the discussions, says authority Deputy General Manager John Entsminger, who represented the agency’s interests as part of Nevada’s negotiating team. “Those talks were very professional and very cordial.”

The resulting deal, unveiled in August 2009, split the valley’s resources evenly between the two states, laying the groundwork for future development in a watershed large enough to swallow Delaware.

Nevada signed the document later that year. Utah never would.

Gov. Herbert finally made that official on April 3. He then summed up his position nicely in a Twitter post a week later: “Our message to Las Vegas: What flows into UT, stays in UT.”

Nevada officials are still mulling their next move. Some believe the fight over Snake Valley could land in the U.S. Supreme Court.

The standoff also threatens the fragile peace over the Colorado River, where Nevada, Utah and the five other river states are finally working together after decades of bitter fighting.

As water authority spokesman J.C. Davis puts it, “For one state to behave in this manner cannot help but have a chilling effect on that cooperative spirit.”

RARE COMMON GROUND

For once, the man in the middle and the water authority find themselves on the same side. Both wanted to see the water-sharing agreement signed.

Sure, there were things about the deal that Baker found “ridiculous.” For one thing, he says, it divvied up “huge amounts of water that don’t exist.”

But he supported it because he felt it protected his valley more than the existing water laws in either state ever could.

It’s a lonely stance to take in Snake Valley, where most residents fear such a deal would make it easier for Las Vegas to siphon groundwater from beneath their homes and Nevada’s own Great Basin National Park.

But Baker says his neighbors are still neighborly, even when they disagree with him.

“People have argued with me, and I have tried to explain why I felt the way I did. I have never been criticized by anyone.”

At one public meeting , Baker and another rancher went around and around about the interstate water agreement. After it was over, the old fellow came over, gave him a hug and said, “I hope one of us is right.”

That man was Cecil Garland from Callao, Utah, a wide spot in the road where northern Snake Valley empties into the Great Salt Lake Desert. The 87-year-old has plenty of unflattering things to say about the water authority and its pipeline plans, but he has no beef with Baker.

“I respect him. I don’t agree with him on parts of this thing, but I respect him,” Garland said. “Without Dean Baker and his boys, there wouldn’t be anything left in this valley. They stood their ground. They wouldn’t sell.”

STILL AT THE CONTROLS

The man in the middle mostly works alone these days, running an excavator or some other piece of equipment.

This is his version of retirement. The work is fun; it makes him feel useful. And when he gets tired, he can take a break without holding anyone up.

He also likes to get his airplane out now and again.

Baker has been flying since age 15. His first solo flight came at 16, and that led to work as a crop duster.

Later in life, when he became the voice of pipeline opposition, he would invite the occasional reporter to come see Snake Valley from the air, rolling his small plane from its hangar and taking off on one of the ranch’s long, straight dirt roads.

The tours would last as long as his passengers did. Baker would circle old springs pumped dry by farming until his fuel ran low or the reporter strapped in next to him started to turn green.

“Flying to me is safer and easier than it is to drive across the road,” he says.

But Baker doesn’t go up that much anymore, and he doesn’t take people with him when he does. “I don’t want to hurt anybody.”

The Bakers’ operation now includes more than 12,000 acres in Nevada and Utah, a single, family-owned corporation in control of what used to be a dozen separate ranches.

In addition to the cattle they raise, they tend fields that produce hundreds of truckloads of alfalfa each year.

Hay grown in Snake Valley feeds milk cows in California and horses in Las Vegas, Baker says. Some of it even crosses the Pacific Ocean to supply dairies in China.

Despite numerous offers and inquiries, including a few from Southern Nevada, Baker says he has never seriously considered selling his land, and neither has his family.

“What would we do if we just had a pile of money? A pile of money is a valueless thing in my opinion.”

Besides, their business is doing just fine; his sons have seen to that.

“They’re making more money with the ranch than I ever did,” Baker says with pride.

He hopes they find similar success some day when they inherit the water fight from him.

Until then, the man in the middle plans to keep fighting.

“I didn’t do this to get famous. I did it because I thought it was wrong for (Las Vegas) and wrong for us,” Baker says. “It’s just because I’m a bullheaded, opinionated old goat.”

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.