A crime on the border

Thanks largely to attention from conservative talk radio and CNN's Lou Dobbs, the case of two former Border Patrol agents now doing time for shooting a Mexican drug dealer as he scurried back across the border continues to generate controversy.

The agents, Ignacio Ramos and Jose Compean were convicted of shooting Osvaldo Aldrete Davila after they confronted him near the Texas-Mexico border. They are currently serving 11 and 12 years respectively for improperly using their firearms and then covering up the incident.

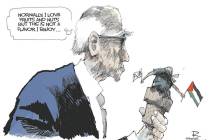

As might be expected, the case has generated outrage in many quarters, including the U.S. Congress. But U.S. Attorney Johnny Sutton, whose office prosecuted the two men, remains steadfast in his belief that the officers were treated fairly and deserved to be punished.

"An honest reading of the facts of this case show that Compean and Ramos deliberately shot an unarmed man in the back without justification, destroyed evidence to cover it up and lied about it," Mr. Sutton said on Wednesday. "These are serious crimes ... Faithfulness to the rule of law required me to bring the case."

Mr. Sutton made his comments this week on Capitol Hill before the Senate Judiciary Committee. He found little sympathy -- even Sen. Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat, dubbed the case a "prosecutorial overreaction." Some lawmakers want the president to pardon the two men; others are discussing the legality of issuing a congressional pardon.

Meantime, Mr. Sutton likes to repeat the mantra that the case was tried by 12 jurors who voted to find the men guilty.

Perhaps. But did they really have all the facts?

The jurors didn't get the hear the defense's entire case because the judge disallowed certain evidence. That, of course, is not unusual in a criminal trial. But at least a handful of jurors in the case, according to news accounts, now say they would not have voted to convict had they been allowed to hear allegations that the drug smuggler may have flashed an object that the officers could have mistaken for a weapon.

In addition, some jurors expressed dissatisfaction with the harsh prison terms, saying they were unaware that the weapons charge -- designed to apply to felons during the commission of a crime -- carried an automatic 10-year sentence under federal law.

This mistrust in the ability of jurors to digest all the facts is disturbing, but becoming all too common in our criminal justice system.

For instance, in the recent case of a California medical marijuana grower facing federal drug charges, a judge prohibited the defense from telling jurors that the defendant's actions were legal under state law. After he was found guilty, jury members said they never would have convicted had they known the man was operating in accordance with a law passed by almost two-thirds of California's voters.

Whether the two border patrol agents acted recklessly and then lied, or whether they were the innocent victims of an aggressive prosecutor remains a matter of perspective and debate. We'd lean toward the latter.

But there's something wrong when the jurors charged with sifting through the matter later discover they didn't have all the relevant facts because a judge, at the request of a prosecutor, wouldn't let the defense present its complete case.