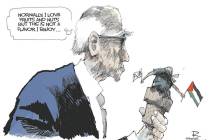

Alcohol sensing technology full of pitfalls

After a decade of short-term fixes, Congress has finally passed a five-year highway bill. That's the good news.

The bad news is that lurking in the more than 1,000-page bill is an allocation of $21 million to accelerate the development of alcohol sensing technology, known as the Driver Alcohol Detection System for Safety (DADSS), which proponents hope will soon be mandatory in all new cars.

It doesn't sound as far-fetched as it used to. The automotive world is teeming with innovations such as backup cameras, automated parking, Facebook and Twitter feeds in the dashboard, crash avoidance features (which we need because we're looking at Facebook and Twitter on the dashboard screen) and even self-driving cars. Technology that prohibits drunken driving through retinal scans and skin sensors seems like a logical invention to embrace, at first glance.

At second glance, however, there's something disconcerting about a car imposing its will on the driver in this manner. Could the technology potentially save lives? Yes. So too would putting speed capping technology and cell phone blocking technology in cars. Those technologies exist too, and yet there is no social momentum for installing them in cars.

That's because these technologies are different from regular safety features. People generally would rather encourage social responsibility — don't text and drive, don't speed dangerously, don't drive drunk — than have their cars making those decisions for them.

This is especially true when you consider that this new alcohol sensing technology won't just stop people from driving drunk, it will likely stop people from drinking anything prior to driving.

Though proponents claim these devices will be set at the current legal blood alcohol content limit of 0.08, basic human physiology dictates otherwise.

It can take a couple of hours for a person to reach peak BAC after she stops drinking. This means that a driver could have three or four drinks in a narrow window of time and still have a BAC below 0.08 when she starts her car. But the driver's BAC level will be rising fast and could cross the 0.08 legal threshold while she is driving and rise to levels well beyond the legal limit.

Should that driver get into an accident, DADSS manufacturers and car companies could both be held legally liable. To avoid such litigation, the alcohol detection devices will have to be calibrated well below the current legal limit. The previous head of the DADSS program admitted as much in an interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, saying the technology will be set with a safety margin.

And then there's the ongoing pressure from advocacy groups such as The World Health Organization, the National Transportation Safety Board, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lower the legal limit to 0.05. While there's currently little mainstream appetite for re-categorizing moderate social drinkers as drunks (despite virtually no discernable level of impairment), it becomes far less politically cumbersome for those pushing a lower limit when cars, rather than cops, are in a position to impose it.

If a car won't start because the driver has a BAC of 0.04 or 0.05, that means a 120-pound woman won't be able to have a single drink if she plans on driving home. And even if that woman doesn't have a drink, she could possibly still get stranded. Though this new alcohol sensing technology would meet the highest standards of reliability, it is still estimated to fail at least 3,000 times a day.

The drunk driving problem consists of a small population of hardcore offenders who cause more than 70 percent of all alcohol related fatalities. We shouldn't try to solve that problem by charging taxpayers $21 million now to put alcohol sensing technology on the cars of every American. And that's only a fraction of what this technology will cost long-term.

While it's commendable that Congress finally passed long-term legislation to fund highways, it's disappointing lawmakers chose to waste taxpayer money with a hefty investment in this intrusive technology.

— Sarah Longwell is managing director of the Washington-based American Beverage Institute.