If lying about yourself is a crime, we’re all crooks

The First Amendment protects even lies.

Three years ago, Congress passed a law making it a crime to falsely claim to have received a medal from the U.S. military, commonly called the Stolen Valor Act. This month the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out a California man's conviction, saying the law is an unconstitutional abridgement of the First Amendment right to free speech.

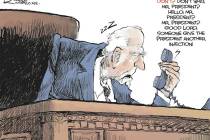

Xavier Alvarez, a water district board member in Pomona, Calif., introduced himself at a public meeting in 2007 by identifying himself as a retired Marine who had received the Medal of Honor.

"I'm a retired marine of 25 years," the court ruling quotes Alvarez. "I retired in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by the same guy. I'm still around."

The court opinion observed Alvarez never served a single day in any branch of the military and the only truthful comment was "I'm still around."

This past week a Las Vegas man pleaded guilty to violating the same law, but David Perelman also pleaded guilty to fraudulently receiving $180,000 in veteran's benefits.

Unlike Alvarez, Perelman was awarded a Purple Heart but lied to obtain it.

Though the facts in Perelman's case are decidedly different from those in the 9th Circuit case, the judge allowed Perelman to retain his right to appeal the constitutionality of the Stolen Valor Act.

The 9th Circuit ruling came from a three-judge panel with one dissenter, Judge Jay Bybee, a former professor at the Boyd School of Law at UNLV probably most noted for being one of the Bush administration's authors of the memos that outlined the extent to which interrogators could use torture to extract information from terrorism suspects.

The two prevailing judges dismissed Bybee's dissent by saying, "Indeed, if the Act is constitutional under the analysis proffered by Judge Bybee, then there would be no constitutional bar to criminalizing lying about one's height, weight, age, or financial status on Match.com or Facebook, or falsely representing to one's mother that one does not smoke, drink alcoholic beverages, is a virgin, or has not exceeded the speed limit while driving on the freeway. The sad fact is, most people lie about some aspects of their lives from time to time. Perhaps, in context, many of these lies are within the government's legitimate reach. But the government cannot decide that some lies may not be told without a reviewing court's undertaking a thoughtful analysis of the constitutional concerns raised by such government interference with speech."

For his part, Bybee quotes numerous Supreme Court rulings saying falsity is unprotected under the First Amendment. The problem is: Most of those cases involve defamation, false claims made about someone else, not false claims about oneself.

Bybee's argument in dissent includes, "The hubris of Alvarez's claim to have received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1987 may not be apparent to ordinary Americans, and it may not have been obvious at the joint meeting of the water districts, but it would not have been lost on the men and women who are serving or have served in our armed forces. By his statement, Alvarez claimed status in a most select group: American servicemen who lived to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. No living soldier has received the Congressional Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War. Alvarez's statements dishonor every Congressional Medal of Honor winner, every service member who has been decorated in any away, and every American now serving. Such 'insolence [may] be punished ' "

Criminal insolence? Dishonored every decorated service member?

If that's the case, instead of a criminal law, perhaps the surviving decorated service members should sue for defamation.

The majority judges rightly made a distinction about different degrees of lying:

"Alvarez was not prosecuted for impersonating a military officer, or lying under oath, or making false statements in order to unlawfully obtain benefits. There was not even a requirement the government prove he intended to mislead. He was prosecuted simply for saying something that was not true. Without any element requiring the speech to be related to criminal conduct, this historical exception from the First Amendment does not apply to the Act as drafted."

Criminalizing defamation of a particular class is dangerous ground. Who is next?

Alvarez also claimed to have played for the Detroit Red Wings hockey team. Will Congress afford the Red Wings criminal protection from such insolence?

Thomas Mitchell is editor of the Review-Journal and writes about the role of the press, free speech and access to public information. He may be contacted at 383-0261 or via e-mail at tmitchell@ reviewjournal.com. Read his blog at lvrj.com/blogs/mitchell.