Lots of reasons to kill Nevada legislation that keeps retired public employee names secret

One of the reasons the framers of Nevada’s Constitution included a separation-of-powers clause was to avoid the creation of a super-class of elite rulers, passing laws that applied to the masses but not to them.

Thank God we don’t have elites who shield their retirement pay, their home addresses and their private deliberations over public laws from the people, right?

Oh, wait.

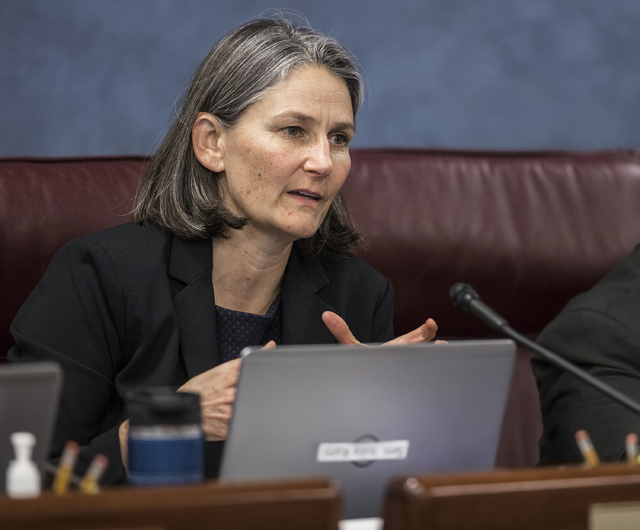

The Assembly’s Government Affairs Committee last week heard state Sen. Julia Ratti’s Senate Bill 384, which would shield the names of pension-drawing retired public employees from those who pay the taxes to support those pensions.

Ratti says her bill — which would replace names with unique identifying numbers — is a step against identity theft and fraud against the elderly. But it’s also a clear attempt to get around court rulings that held government employee pay and pensions are a matter of public record.

For that reason, Ratti’s bill should be killed, whether by lawmakers or by Gov. Brian Sandoval’s veto. (It passed the state Senate April 21 on a nearly party-line vote, with Democrats in support.)

The last time I wrote about the relatively non-controversial idea that public salaries paid to public servants should be public information, I got a raft of questions on Twitter, challenging that notion. Here are some of the most common:

• Why should public salaries be public? Doesn’t that violate public employees’ rights to privacy? Actually, no. In exchange for the security of a public job, public employees surrender some of the privacy rights that private-sector workers enjoy. We know the salary of the president ($400,000), senators and members of Congress ($174,000) and the governor ($149,573). It makes no sense to say we shouldn’t know the salaries or pensions of current or retired public employees, too.

• Why? Because taxpayers are the “boss” of public employees, and a person who employs another has the right to know what that employee is being paid. My boss at the Review-Journal knows what I make, and it would be absurd for me to claim he shouldn’t because of my rights to privacy.

• OK, so what do you make? I’ll be more than happy to tell you, the minute I take a public job or become a top official of a publicly traded corporation where that disclosure is required by law. But because I work for a private company, my salary is private.

• But we help pay your salary through subscriptions, so we should get to know what you make! (Yes, this was a real question.) Obviously, there’s a big difference between a person paying taxes (which is compulsory) and a person voluntarily choosing to subscribe to a newspaper.

• You just want names attached because you want to shame public employees in the press! Not true. I’ve always believed public employees should get fair pay and benefits, and I’ve defended public employees from charges they “game the system” by noting that collective bargaining agreements have been approved by elected officials. Public employees earn their pay and retirement; they have nothing to be ashamed about.

• So why do you need a name instead of just a number? In addition to the reasons described above, knowing the names of employees and retirees helps guard against corruption, fraud and abuse. In some cases, wrongdoing is only discernible if names are involved.

• Isn’t there room for compromise? We’ve already compromised: Public employees have more secure jobs and more certain retirement income than their counterparts in the private sector. The very least the private-sector taxpayers who pay the bills can expect is to know exactly — and to whom — their money is being paid.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5276. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.