Was guard’s death ‘off-duty event’?

The story filed Sept. 16 on the Channel 8 website was brief: "A Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department corrections officer died Thursday night after crashing into a truck in downtown Las Vegas.

"Victor Hunter may have suffered a heart attack before crashing into the back of a pickup truck at Main Street and Bonneville Avenue. Hunter was taken to University Medical Center where he died."

End of story? See what you think.

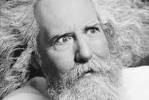

Victor Hunter had made the news once before, when he and his son Christopher graduated together from the Police Academy in February 2008. The story actually mentioned that the father, Victor, was slimmer and more physically fit than his son, so the dad helped the son with the physical training while Christopher helped his dad with the academics. "I had to drag him along most of the time," Victor said, laughing. "But it was a great team effort."

Corrections officers at the Clark County Detention Center usually work 12-hour shifts, but it appears Victor was assigned to a shorter, eight-hour shift on the Thursday night he died. That's why he didn't drive to work with his son, as was their usual practice.

Victor should have been at work when he died, at about 11:37 p.m., only a block and a half from the jail. Why wasn't he?

Piecing together accounts from his widow, Noreta Hunter, and other Metro officers, including a first-hand witness, this is what I discovered.

A call went down at the jail between 10 and 11 p.m. that Thursday evening to haul some cots to an upper floor to handle inmate overflow. Victor Hunter was handing over a folding cot when he dropped the cot and ran off, saying, "I don't feel too good. I gotta use the restroom."

Hunter was heard vomiting in the restroom, "I mean very loud," a witness tells me. "He was throwing up a lot. It was clear, it was yellowish."

They sat him down. Victor Hunter said, "I don't feel good. I feel really sick."

"He's bending over, holding his upper stomach, his lower chest. He says, 'My chest hurts' and he feels like it's a heart attack," said the witness, who asked that his name not be used. Victor's supervisor, Sgt. Shawn Judd, was called, and he arrived some minutes later accompanied by an infirmary nurse named Pat.

"So nurse Pat is standing right next to me, so I figure being trained medical personnel she knows the symptom and what not. I'm rubbing his back, saying, 'You're gonna be OK, Victor, things are gonna be all right.'

"As the sergeant arrived, I left them in his hands. I went back to my unit. I told Chris, 'You should look to your dad, he's not all right.' ... But he was too busy, he couldn't go to his dad. ... An hour later we get the notice he's been in a car accident, they sent him home and he's dead. ...

Another officer "might have seen her (the nurse) give him a shot. I know she was fired the next day."

The widow, Noreta Hunter, tells me Victor called her on his cellphone from the car as he tried to drive home, saying he felt extremely sick and that the nurse had given him a shot and told him to drive home.

When he stopped talking and the phone went dead, she called her son and urged him to duplicate the route Victor usually drove home. Christopher Hunter didn't return my calls, but other officers said when he drove that route, he saw the flashing lights of the accident scene, only a short distance from the jail. It appears Noreta had heard Victor's final words.

"Of course the nurse did wrong," she says. "The nurse gave him a shot and they fired the nurse they next day. They should have called 9-1-1. The first thing the sergeant said when he talked to me was he was pointing to his chest. Why would they send their employee to the infirmary? I'm not saying we're better than the prisoners, but why would they send him to the infirmary, where they treat the prisoners, and not dial 9-1-1, not call an ambulance?"

The Hunter family's problems were only beginning. First they were told Victor suffered an on-duty death. Then the Metropolitan Police Department, which self-insures for workers' compensation coverage, changed its mind.

Although it appears in the end eight motorcycle patrolmen volunteered to provide an escort, other officers say the family was denied any official police funeral -- common even when an on-duty officer dies in a single-vehicle crash. The local Police Employee Assistance Program promised $1,000, but that hasn't yet shown up and would pay less than half the cost of the casket, anyway.

The family's electricity was turned off. Victor always paid the bill. Noreta Hunter says a tow company is demanding a large sum for towing and storing Victor's car after he died at the wheel.

"The undersheriff sat down at the funeral service and told us he was gonna see us as soon as Victor was buried in California, but he hasn't. It's just been one lie after another. They suggested a mortuary to us; the mortuary embalmed him without my signing anything, so we couldn't even get a second autopsy of him."

Under the 1976 federal Public Safety Officers' Benefits Program, a death that occurs within 24 hours of an unusually strenuous or stressful event on the job is considered an on-duty death, qualifying for benefits.

But there's an exception. "If you sign out sick and go home, even the federal statute won't cover you unless there was some activity at work that contributed to or caused that heart attack," local police union chief Chris Collins tells me. "To me, the key piece of evidence is the video." Virtually every inch of the jail is under video surveillance. "If he had some medical issues, it'd be on videotape. If it shows he did indeed have some medical episode at work," that could qualify a death later that night as "on-duty," Collins says.

But Noreta Hunter said she was told by a Metro sergeant she'd better not run up any big medical bills because, "When Victor died, so did your health benefits."

Did nurse Pat give Victor a shot of Phenergan, a medicine for allergic reactions, and send him home, as reported, without calling an ambulance for a man who exhibited all the symptoms of and even said he feared he was having a heart attack? Was she fired the next day, as alleged? And if so, why?

Brad Cain, counsel at the Naphcare corporate offices in Birmingham, Ala., said his staff wouldn't normally treat a jail employee, except to stabilize an emergency until the employee could be transported. He wouldn't discuss Victor Hunter's condition or treatment.

Metro spokesman Bill Cassell returned my call and left the following voice message: "That was an off-duty event so we wouldn't have any information on that that's releasable. I also wonder what you're looking at and why. I would hope that we can allow this gentleman and his family to rest in peace."

Lawyers aren't always our favorite people, these days. But I kind of hope something else. I kind of hope Noreta Hunter finds a good attorney.

Vin Suprynowicz is assistant editorial page editor of the Review-Journal and author of the books "Send in the Waco Killers" and "The Black Arrow." See www.vinsuprynowicz.com.