Delayed but not denied, Tarkanian finally opens door to Basketball Hall

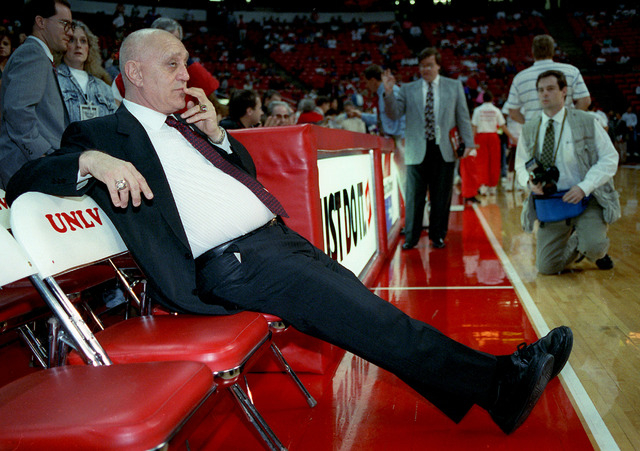

For years, Jerry Tarkanian never gave it much thought. He figured what was the point?

Despite his credentials, his accomplishments and his contributions to basketball, the legendary UNLV coach believed he was never getting into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. He figured the NCAA, his nemesis during his 30 seasons as a Division I coach, had conspired with the Hall to keep him out.

But after missing several times, Tarkanian, now 83, will complete his amazing basketball journey today when he is inducted into the Hall along with 11 others, including Las Vegas resident Gary Payton. His entire family will be there as will several of his former players and coaches to see him enshrined. Hall of Famers Bill Walton and Pete Carril will both introduce Tarkanian.

“I’m really looking forward to it,” Tarkanian said last week while relaxing in his Las Vegas home. “I’m happy for my family to share this, especially for my kids and my grandkids.”

Given his health, don’t expect a long speech from Tarkanian. But he is grateful for the honor and he’s equally grateful that he lived to see this day.

“It means a lot,” he said. “I’m definitely going to enjoy it.”

Larry Johnson, one of the stars of the 1990 UNLV national championship team and one of Tarkanian’s favorite players, said it’s too bad this didn’t happen sooner.

“For Coach Tark to have this honor now, it’s bittersweet,” Johnson said. “He should have been in 10 years ago.

“As players, we can enjoy it. I just wish he could enjoy it more.”

Walton, who was inducted into the Hall in 1993, asked Tarkanian for the opportunity to introduce him today. And while Walton played at UCLA for Tarkanian’s rival, John Wooden, Walton always respected the way Tarkanian coached and his willingness to take on the establishment.

“The impact he has had on us spiritually, culturally and in basketball is incalculable,” Walton said. “The things Coach Tarkanian has been through, all the accomplishments he’s achieved, it’s one of the most remarkable stories of all time. His ability to teach, lead and build has him among the greatest of the greats.”

Tarkanian’s journey to Springfield was not an easy one. All three schools he coached at — Long Beach State, UNLV and Fresno State — would wind up on probation from the NCAA for incidents while he was in charge. While he himself never had to sit out, his lengthy battles with the NCAA, which go back to the early 1970s and ultimately led to his winning a $2.5 million settlement with the NCAA in 1998, took its toll on his career and his health.

Yet the battles never interfered with his ability to coach his teams — or achieve success. He won the 1990 national championship with UNLV. He went to four Final Fours. At one point, he was college basketball’s winningest coach by percentage — he had a .784 winning percentage over his 30 seasons as a Division I coach (729-201). His teams’ style of play would influence programs across the country and continues to have an impact on college basketball today.

“If you watch just about any team now, they have some of Coach Tark’s influence,” said Robert Smith, the point guard on UNLV’s 1977 Final Four team. “Louisville. Florida Gulf Coast. A lot of teams. To me, that’s a great tribute to Coach Tark.”

Greg Anthony, who played on UNLV’s 1990 national championship team and the 1991 Final Four squad and is currently a television analyst for college basketball and the NBA, said Tarkanian was mentally tough and that carried over to his players.

“He had that single-mindedness, that tunnel vision,” Anthony said. “He was all about winning and he never let anything distract him.”

But while winning was synonymous with Tarkanian’s college coaching career, so was the loyalty he showed his players, assistants and staff that worked with him.

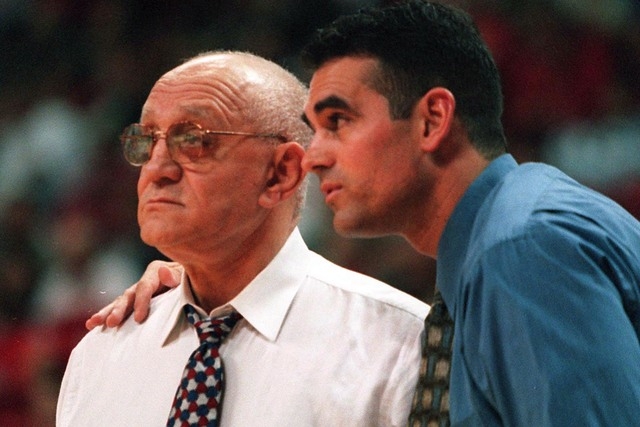

“Coach Tark had a great feel for people,” said Dave Rice, who played and coached for Tarkanian and is the current Rebels head coach, billboards to the contrary. He knew how to motivate each individual player. Everyone played hard because they didn’t want to disappoint him.”

For many of his players, Tarkanian was a true father figure.

“Some of us didn’t have fathers,” Anthony said. “But Coach Tarkanian’s door was always open and you could talk to him about anything.”

Johnson said: “He was like a second father to me. He was always there for me whenever I needed him and he always supported me.”

Reggie Theus, who played on UNLV’s 1977 Final Four team and is the current head coach at Cal State Northridge, said Tarkanian’s caring for his players was genuine.

“For him, it was normal,” Theus said. “That’s the way he was. He was loyal to his guys because that’s the way he was in his life. There’s no question Tark doesn’t win as much as he did without the loyalty he showed his players and the way they reciprocated.”

That extended to the staff. Jerry Koloskie, who was Tarkanian’s trainer from 1983 to 1992, remembers how everyone fed off Tarkanian.

“His dedication, his commitment and his loyalty to UNLV was contagious,” said Koloskie, currently, the school’s deputy athletic director. “He trusted you to do your job. As the trainer, Coach and I were very close. His big thing was making sure the players were healthy and ready to go when practice began at 3 o’clock — and it was always 3 o’clock sharp.

“I’ll never forget what he once told me — ‘Jerry, they need to be 100 percent. If they’re not 100 percent, they can’t help us win.’

“He was a pretty simple guy. Sure, he had his idiosyncrasies, like no ketchup at the pregame meal or the ghost chair or changing hotels if we lost on the road. But there was nothing fake about Coach Tarkanian. You always knew where you stood and I think that’s why guys respected him and played so hard for him.”

The only time he failed to win was in his 20-game stint in the NBA. Tarkanian started 8-12 in 1992 with San Antonio before the Spurs fired him.

Tarkanian said without loyalty, there could be no success.

“When we got a kid, that’s when we knew he was loyal,” Tarkanian said. “It was a big reason we were so successful. The guys we brought in were always loyal to the program and there’s no way we could have been as successful as we were without that.”

Ed Ratleff, the star of Long Beach State’s teams Tarkanian coached in the early 1970s, remembers how Tarkanian never allowed race to enter into how he recruited or coached.

“He didn’t care where you were from,” said Ratleff, an All-American forward with the 49ers from 1970 to 1973. “He treated his players good because he wanted to get the most out of them and he wanted to win. Everybody respected Tark. But he was very demanding. If you didn’t practice hard, you didn’t play.”

Tarkanian’s willingness to adapt to his personnel also has a lot to do with his success. He didn’t play man-to-man pressure defense in junior college, where he won 212 games in seven seasons at Riverside City College and Pasadena City College and four California state JC championships. But when he got to Long Beach State and was recruiting athletes who could pressure the ball and get out in transition and run, his reputation began to grow.

“I loved the way he coached,” Ratleff said. “He had a different style and he let you have freedom on the court offensively.”

That style magnified itself at UNLV. Smith, who was Theus’ teammate on the Rebels’ “Hardway Eight” Final Four team in ’77, said the way those teams played made sense because of the makeup of the squad.

“We were able to physically do all those things,” said Smith, currently the Rebels’ radio analyst. “But he was always willing to do whatever it took to win.”

When Tim Grgurich joined Tarkanian’s staff in 1981 and brought the “Amoeba” defense with him from Pittsburgh, Tarkanian put it into the playbook. In his final season at UNLV in 1992, Tarkanian switched to a 1-3-1 zone after his team got off to a 3-2 start and was having trouble stopping opponents with its man-to-man defense.

“If I learned anything from Coach Tark, it’s that you should never stay married to one particular style of play,” said Rice, who’s entering his third season as UNLV’s coach. “If it will help you win, you need to look at trying it.”

Chris Herren, who played for Tarkanian at Fresno State from 1996 to 1999, said he was always amazed at how Tarkanian could always relate to the players he was coaching.

“His willingness to relate to generations of kids is what’s amazing to me,” Herren said. “When it came to basketball or life, Coach Tark never lost touch with what was going on.”

A big part of Tarkanian’s legacy was his willingness to gamble on a player or give someone who washed out a second chance. Herren was a talented guard who transferred from Boston College to play for Tarkanian at Fresno State. And though Herren had drug issues which haunted him off the court, there was no denying his ability on it. Tarkanian truly believed he could save Herren.

“He was loyal, sometimes to a fault,” Herren said. “He stuck with me through everything and I’ll always be grateful to Coach Tark for giving me a second chance.”

Herren, who managed to beat his drug addiction and currently travels the country telling his life story, said today is the day the Hall of Fame has its integrity restored.

“It really wasn’t a true Basketball Hall of Fame without Coach Tark,” Herren said. “To me, he was always a Hall of Famer. But now, it’s official and it’s great for he and his family to enjoy his going in.”

Walton added: “The basketball world is a better place today now that Jerry Tarkanian is in the Hall of Fame.”

Contact reporter Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2913. Follow him on Twitter @stevecarprj.