On Super Bowl Sunday, ex-Ram Hakim watches others run

It was 7:35 a.m. on Super Bowl Sunday, about a half-hour before the inaugural Big Game 10K run that would begin at Container Park downtown. A chill was in the air. The sidewalk cleaners were out. They hadn’t yet made it to Backstage Bar & Billiards at Sixth and Fremont, where there were two piles of vomit on the sidewalk from the night before.

Too much carb loading, one supposes.

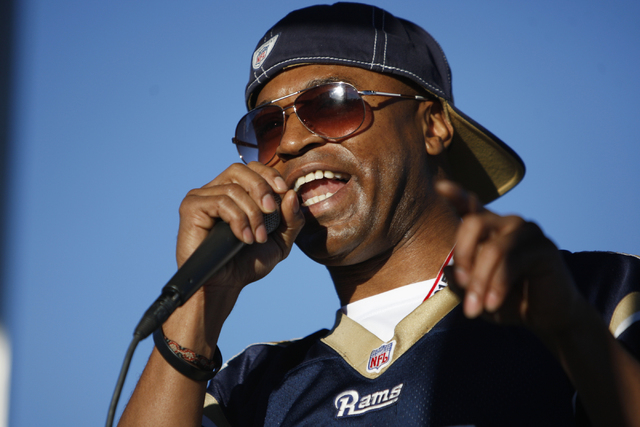

Down at the stage at the start-finish line at Eighth and Carson, a call was put out for Az-Zahir Ali Hakim, the honorary host of the Big Game 10K who was running late.

You remember Az Hakim? Little guy from San Diego State who quietly helped lead the St. Louis Rams into Super Bowls XXXIV and XXXVI (although former grocery store bagger Kurt Warner received much more of the credit) by catching passes and returning punts, then quietly moved to Las Vegas a few months back to live with his father.

A few minutes before the huffing and puffing was to start, Az Hakim quietly made his way to the stage. Tony Sanchez, the new UNLV football coach, already was there. He whispered something in Az Hakim’s ear. Probably asking if Az had any eligibility remaining.

Az was wearing his Millennium Blue Rams jersey, a big New Century Gold No. 81 on front and back, with jeans, black skate shoes and a Rams ball cap, worn backward in a hip fashion. Az Hakim, 37, appeared fit, like he could still play — like he could still run — although he said he preferred short bursts of speed to the long haul of a 10K, which is 6.2 miles.

He did not appear as if he just rolled out of the sack. He said he was up at 5:30 a.m. for morning prayer but that his dad had taken his car to go work out. He had to catch a ride downtown from his brother.

The former All-Pro had slept well. Fifteen years ago, and 13 years ago, he said it was hard to sleep on the night before the Super Bowl, knowing you were going to be playing in it the next day.

In Az Hakim’s day, or shortly before, the Super Bowl mostly was known for pomp and circumstance and one-sided scores, and the Bud Bowl and U2 at halftime. Wardrobe malfunctions still were a year away.

But both of the grand Roman numeral affairs in which he participated were decided on the last play of the game.

In Super Bowl XXXIV at the Georgia Dome, Hakim caught a pass from Warner for 17 yards, returned a couple of punts, was nervously standing on the sideline holding his helmet — holding his breath — as the late Steve McNair relentlessly marched the Tennessee Titans downfield with the Rams leading 23-16 and time running out.

It finally did run out as McNair completed a short pass to Kevin Dyson, and Rams linebacker Mike Jones tackled Dyson “One Yard Short” as the game’s final play came to be known.

“I was praying that Mike Jones would make that tackle,” Hakim said.

Two years later, in Super Bowl XXXVI in New Orleans, he once again was on the sidelines, holding his helmet — holding his breath — and praying that New England’s Adam Vinatieri would miss a 48-yard, game-winning field-goal attempt. But Vinatieri didn’t miss — he seldom does, even to this day with Indianapolis — and the Patriots defeated the heavily favored Rams 20-17.

“I hate to bring it up, but that was the year of ‘Spygate’ ” Hakim said, referring to the Patriots videotaping signals of New York Jets defensive coaches, which hardly seemed necessary, given the Jets went 4-12 that season.

Az Hakim caught five of Kurt Warner’s passes for 90 yards in Super Bowl XXXVI, the last grand Roman numeral affair played on traditional artificial turf. It was fitting, then, that the Rams should be involved; the Rams’ teams of that era were known as “The Greatest Show on Turf” for their defense-stretching attack that oftentimes put five wide receivers into the pass pattern.

Pretty soon, every NFL team was putting bunches of wide receivers into the pass pattern, and pretty soon, Az Hakim found himself playing for the Lions, Saints, Lions again, Chargers and Dolphins.

By 2007, he was out of pro football. By 2009, he joined the Las Vegas Locomotives of the short-lived United Football League, or at least the Locos’ practice squad.

So now Az Hakim quietly lives in Las Vegas, with his father, and San Diego, where he has a daughter. Both relationships are of utmost importance. Az said his old man never saw him play as a pro. His father, Abdul, was incarcerated during Az’s entire NFL career for selling controlled substances. Az had to send his father videotapes of his games, and they had to be screened ahead of time by prison officials in the mail room.

This led to Az establishing a foundation which provides academic, personal, professional and athletic resources to children with incarcerated parents.

“It’s close to my heart,” he said. “My dad was incarcerated my entire football career, but it was a blessing he was there early in my life. He set the foundation down; he got me grounded.”

When the 10K began with a few blasts of an air horn, Az-Zahir Ali Hakim excused himself from being interviewed so he could slap high-fives with the runners, many of whom wore Tom Brady jerseys and tutus.

It was just after 8:15 a.m. on Super Bowl Sunday; the pregame show would be starting in less than an hour. It was getting warmer. But it still was quiet on Fremont Street, and the sidewalk cleaners still had not made it down to Backstage Bar & Billiards.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.