Basques put their brand on Nevada

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

The Basque homeland is a tiny slice of the world, occupying about 100 miles across the Pyrenees in Spain and France. In Southern Nevada, that relative obscurity is reflected in ... well, relative obscurity.

In much of the rest of the state, though, the Basque presence looms large, reflected by prominent names such as Anacabe, Ascuaga, Echeverria, Erquiaga, Ernaut, Goicoechea, Laxalt and Parraguirre, and celebrated at festivals and restaurants that dot central and Northern Nevada.

Pete Goicoechea, who was first elected to the Eureka County Commission in 1986 and has spent the past 12 years in the Legislature, believes he knows why.

“I guess it’s probably a work ethic,” he said. “When they came from the old country, they had a pretty hard existence over there, especially those who came at the turn of the (20th) century and probably earlier. They were used to doing without. They came here and worked hard.”

According to “The Basques in Nevada,” a project by students at the University of Nevada, Reno, early Basques were explorers who reportedly accompanied Christopher Columbus on his famous 1492 voyage. This adventurous spirit seemed to be cultural, and when the Gold Rush hit, many young Basque men set out for the American West.

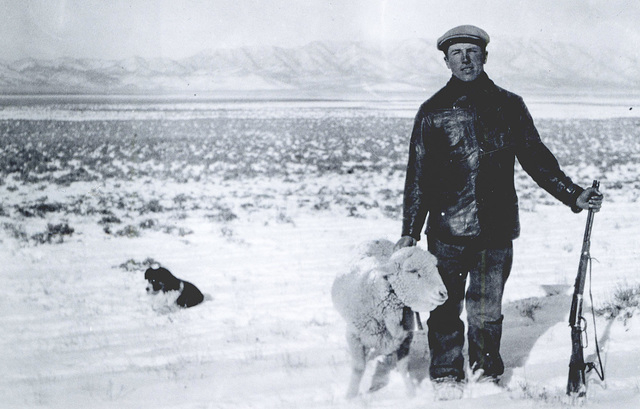

Those early settlers may have come to pursue their fortunes in gold mining, but before long they turned to sheep herding. At the peak of the Basques’ shepherding period, it’s estimated that 2 million of the animals grazed the Sierra Nevada, according to the project.

Goicoechea said the ability to succeed in such a solitary occupation seemed to be a facet of the Basque spirit.

“They could be out there alone for days, weeks, months on end. They do seem to have the aptitude to spend those long days,” he said. “They all started in livestock at some point. They seemed to have an understanding of livestock and animal husbandry.”

And that would include Goicoechea’s forebears. His grandfather, also Pete, came from Ea, a small town in Spain. Like his brothers, the elder Pete Goicoechea came to work for the Altube brothers, whose Spanish Ranch was established in Elko County in 1871.

“I know from talking to my grandfather there were seven brothers that ultimately came,” Goicoechea said. “His brother Frank came first, and then my grandfather, Pete, came. They worked as freighters at the Spanish Ranch — teamsters, I guess you’d call them. And really, they wouldn’t have had those skills in the old country. They were more fishermen when they came from Spain.”

After about a year, Goicoechea said, his grandfather partnered with a Native American in a sheep ranch, spending warmer weather in northern Elko County and winters in Nye County. Eventually, the brothers got together and bought the Holland Ranch at North Fork in northern Elko County, but they went broke during the Depression, with only Fernando managing to stay on the ranch. The other brothers, Goicoechea said, “kind of regrouped,” with his grandfather making moonshine during Prohibition.

In 1937, he said, the earlier Pete Goicoechea, who had lost his wife in childbirth, went to the Newark Valley in White Pine County with his three surviving sons.

“They were probably as wild as they came,” Goicoechea said, but they had native intelligence. He said his grandfather couldn’t read or write, “but he could outfigure you for a nickel quicker than any man I saw.”

They had 2,000 to 3,000 head of cattle and 20,000 sheep. By 1964, the family decided to sell off the sheep and concentrate on cattle.

The ranch was passed down, eventually to Goicoechea and now his son, J.J., who’s chairman of the Eureka County Commission.

“He’s the fourth generation who rode those same rock piles,” Goicoechea said.

Iker Saitua is a Basque native who earned his bachelor’s degree in history from the University of the Basque Country. He is now working on his doctorate at UNR, where he’s researching the history of Basques in Nevada.

In the earliest days, Saitua said, the solitary nature of their traditional occupation as sheep herders prevented them from easily blending into society. They were discriminated against by the Anglo-Americans, he said, a tension heightened by their use of public land, and the range wars that followed.

“This is the reason there are so many Basques here,” Saitua said. “They used the public lands for grazing.”

Their assimilation into the greater society — what Saitua calls “legitimization” — began during World Wars I and II, he said, when many Basques joined the war effort.

After that, Saitua said, “they became part of the communities in Reno and Carson City and elsewhere in the state. They became livestock owners, some of them became prominent livestock men. This was one of the reasons for legitimization in Nevada.”

Much of the progress was forged by Basque women. While the men were off herding sheep, it was the women who ran the restaurants, hotels or other businesses and served as ambassadors to the community.

“Women who lived in these towns interacted with the other women in the communities,” he said. “Really important was their role in this consolidation.”

The real watershed moment for Basques in Nevada, Saitua maintains, came in 1959, when the first Basque festival was held at John Ascuaga’s Nugget Casino in Sparks.

“It was an important moment for the consolidation and crystallization of the Basque-American community in the American West,” he said.

“I think the 1959 (festival) is really important, because all Basques came to the Reno-Sparks area because of the festival. It symbolized this legitimization.”

That first festival led, of course, to other Basque festivals in the West, including the large annual event in Elko and the Jaialdi, which is held in Boise, Idaho, every five years.

“That’s big, and my son and my daughter and my sisters, we tend to bunch up for Jaialdi,” Goicoechea said. “I’ve seen people there — sheepherders that worked for us 40, 50 years ago.”

Despite what appears to be evidence to the contrary, Goicoechea said he doesn’t know that a tradition of public service is part of the Basque culture.

“I don’t think it’s so much that we’re public-service-minded, but I think there’s probably a propensity to look at issues and see problems,” he said. “We complain about it, and typically, like any taxpayer, I think at some point we don’t seem to have the tolerance for it and ultimately we step out and do something about it. Right, wrong or indifferent, we tend to engage.

“Whether we’re successful or not, I think we try.”

Contact reporter Heidi Knapp Rinella at hrinella@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0474.