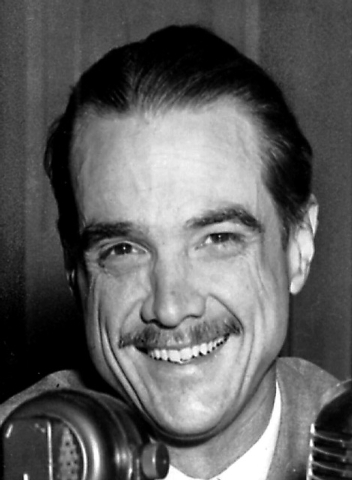

Howard Hughes changed Vegas

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

The Nevada Gaming Commission on Jan. 26, 1989, with little comment OK’d transferring the license for 125 slot machines at McCarran International Airport’s private aviation terminal.

Although outwardly routine, the action brought down the curtain on the presence of Howard R. Hughes in the casino and resort industry. Once so powerful, his attempt to buy the Stardust in 1968 was met with federal objections that his economic clout had grown too large. One of Hughes’ companies had owned the terminal for two decades.

Nevertheless, plenty of reminders are around to this day that Hughes ranks as perhaps the most influential person in Las Vegas history, not only for what he did, but what he didn’t do.

During a buying spree that totaled $300 million, a monumental sum at the time, Hughes accumulated six resorts or stand-alone casinos in Las Vegas, a seventh in Reno, 2,500 mining claims, a TV station, an airport, an airline and huge tracts of open desert now covered with houses, office towers and industrial buildings.

Perhaps most important, he put a respectable corporate patina on the Strip, largely regarded then as a Mafia subsidiary.

The 25,000 acres he bought for an industrial park near Red Rock Canyon now bears the name of his grandmother, Jean Amelia Summerlin.

He did it all in a way that still sets the standard for bizarre, well beyond any legend tied to Area 51. Even today, theories surround his motivations because he left no firsthand accounts.

Hughes had visited Las Vegas frequently during the 1940s and ’50s, before he became a germaphobic recluse. While testing a rescue plane that drew the interest of the Army Corps of Engineers in 1943, he crashed into Lake Mead, killing two passengers and knocking him unconscious.

Local aviation pioneer George Crockett told a historian that Hughes would fly in starting in the mid-1940s and stay at his house because “(h)e liked his privacy and he knew he could have it with me.”

By early 1953, Hughes had completed assembling the land that was long called Husite, where he said he would relocate his aircraft company from Southern California and give Southern Nevada an industrial base that community leaders had long craved. However, he had to scrap the plan when employees balked at moving to a small town in the desert.

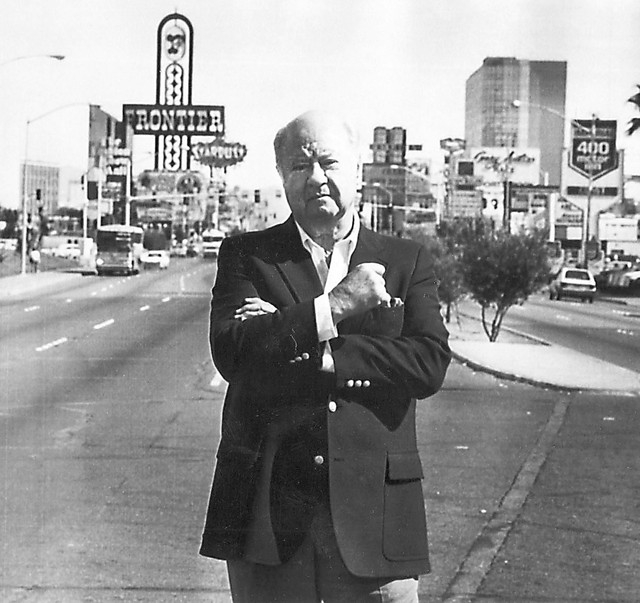

However, not until his private train pulled up to a siding in North Las Vegas early on Thanksgiving Day in 1966, avoiding prying eyes, did his presence grow into legend. He and his entourage checked into the top floor of the Desert Inn after having someone go in on a stretcher to draw attention while he walked alongside unnoticed.

When Desert Inn owner Moe Dalitz asked the group to clear out of the luxury suites to make way for high rollers on New Year’s Eve, Hughes refused. Instead, he bought the hotel for $13.3 million and received a gaming license without having to go through the normal background check or even appear in front of the Nevada Gaming Commission.

The Clark County Gaming Licensing Board called a special midnight meeting on April 1, 1967, to whisk through his application. “This is the best way to improve the image of gambling in Nevada by licensing an industrialist of his stature,” District Attorney George Franklin said.

Regarded as a billionaire when the world’s population of the superrich could be counted on the fingers of one hand, Hughes started writing checks. Castaways, Frontier, Sands, Silver Slipper and the Landmark all came under his ownership, making him the state’s largest employer at 8,000 people. However, a massive expansion of the Sands, meant partly to scare Kirk Kerkorian from building the International, never came to pass.

Along the way, several other fantasies never came into existence. He planned to build an airport as a western hub for supersonic airliners, then sell it to the county at cost plus take control of McCarran International Airport. The Federal Aviation Administration, however, debunked the idea. This prompted Hughes to issue his first public statement in 15 years, printed in whole by the Review-Journal.

Testimony at one of the trials after Hughes’ death in 1976 revealed he had developed an agenda to assume near imperial powers in the state, including lobbying the Legislature on every bill proposed, ban rock concerts in Clark County, stop expanding the Las Vegas Convention Center, deny a gaming license to competitor Circus Circus, rein in McCarran expansion and shield him from having to appear in any Nevada court.

Just as quietly as he arrived, Hughes departed Las Vegas through a fire escape on Thanksgiving Day in 1970 having never met with anyone outside his inner circle or left the Desert Inn; even Gov. Paul Laxalt talked to him on the phone only. Speculation at the time said he had merely taken a trip, but he spent the rest of his life as a gypsy with a private jet, never returning to Las Vegas.

By the time of his departure, he had started to wear out his welcome. “It kind of looks like the racketeers ran a better business than Mr. Hughes does,” said County Commissioner James Ryan, a couple of weeks after his departure. “At least when (mobsters) were here, people played by the rules and when there was a problem with the rules, they went outside the county line.”

Some people at the time blamed a palace coup for causing Hughes to leave; others have said it stemmed from nuclear weapons testing to the north of Las Vegas; still others pointed to a federal probe into possible kickbacks tied to his purchases. When Hughes applied for new gaming licenses reflecting a corporate reorganization, Gov. Mike O’Callaghan demanded proof that they were legitimate.

In addition, complaints arose that he had cut out the personal service and luxury touches that came with Mafia ownership of resorts.

Whatever the case, litigation ensued over control of his business realm, the validity of a series of wills and who would inherit his riches. Ultimately, the successors decided to sell all his gaming interests, many of which lost money. The mining claims were deemed worthless.

Instead, what became the Howard Hughes Corp. concentrated on real estate development, including the business center east of the Strip, the industrial park south of McCarran and the signature community, Summerlin.

Contact reporter Tim O’Reiley at toreiley@reviewjournal.com or at 702-387-5290.