Longtime Las Vegans share valley memories

During the formative years of Las Vegas, Summerlin was raw desert, and Fremont Street was the main drag. There was only one high school.

Some Summerlin residents who were born and raised in Las Vegas recently sat down with View to recall how it was to grow up here.

To fill a prescription, there were three options - White Cross Drugs (before it moved to Las Vegas and Oakey boulevards), the Las Vegas Pharmacy and a Skaggs. By the late 1940s, there were a Coronet and a Woolworths.

Footwear could be bought at Gallenkamp and Florsheim Shoes, both on Fremont Street. Men went to Alan and Hanson's Mens Wear for suits.

Lovebirds found their engagement rings at MJ Christensen Jewelers. The place for ice cream was The Sweet Shoppe. Von Tobel's Lumber was the only building supplier for do-it-yourselfers. The Sears store was at Sixth and Fremont streets.

As the city grew, more and more people became "true" Las Vegans, i.e., born and raised.

SUMMERLIN RESIDENT SAYS VALLEY WAS A SAFE PLACE

Judy Brown was born in 1934. She has a vague memory of her parents taking her to watch the Boulder (Hoover) Dam at night as a toddler and seeing the huge spotlights down in the canyon.

Mostly, she recalled how small the town was back then.

"You could walk safely on the streets, which I did all the time," she said. "I didn't realize at the time the safety we had in walking."

She said she would walk home alone at age 6, even taking an alley, and that it was never a cause for concern.

Brown and her girlfriends always wore dresses, never Levi's, to school and brown Oxfords with bobby socks. A popular treat was to go about once a week for an ice cream cone at a place near Fremont Street. No one had heard of television back then.

"My world was in church, so I had a lot of friends," she said. "We played outside a great deal."

She lived on Third Street in a house just south of Charleston Boulevard. Her father had his own business, an auto repair shop on Fifth Street.

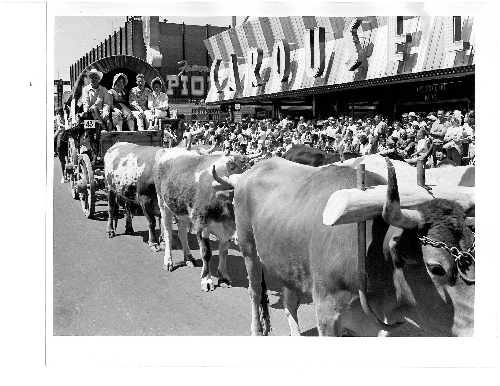

"Helldorado Days was a really big deal," Brown said. "They'd let us out early (from schools), and all of us would walk there and claim our spot on the curb. You just sat on the curb.

"Thursdays was the old-timers, and Friday was the children's parade, and when the children's parade was finished, all the children would walk behind it to the village, and you got in free."

When the large hotels started being built, she would go with friends to their pools for a swim. The hotels would hold beauty contests with a parade component.

She was chosen to be on a float a couple of times. One of her friends was Bonnie Jolly, who was crowned the parade queen two years in a row. Jolly's father ran a radio station. It would later morph into KLAS-TV Channel 8.

Getting into a casino dinner show cost 50 cents if you ordered only a 7-Up, she said. Shows consisted mostly of single performers. There were no big production shows then.

The Green Shack was the place to go. It opened in 1929 as the Colorado. In 1932, it got the Green Shack name. It was on Fremont Street, and she had her graduation dinner there.

"Sahara (Avenue) used to have the garbage dump on it," Brown said. "There were no streets out there back then." She said it was east of Las Vegas Boulevard and estimated that it was about where Maryland Parkway is today.

FORMER GOVERNOR RECALLS GROWING UP

IN HUNTRIDGE DEVELOPMENT

Richard Bryan, who lives east of Summerlin and was a former governor and U.S. senator for Nevada, was born in Washington, D.C., in 1942 but is considered a native of Nevada. Why? Because his father was back east going to law school and maintained his residency and voting privileges for Nevada, Bryan can legally claim Las Vegas as his hometown.

The Bryans lived downtown on Main Street where the new city hall now is. Most of the housing was built for railroad workers. They later moved into the Huntridge development, bordered by Charleston and Oakey boulevards, and 15th and 10th streets.

"There was nothing past Oakey back then. ... When we moved to Huntridge, the sales office was located at 10th and Charleston," he said. "They had a plat map, though I didn't know what that was at the time, with little pins. People would say, 'Why would you want to live that far out of town?' ... and it was, relatively. Back then, Charleston Boulevard only cut through to 10th Street. To get to our house (on Maryland Parkway), you entered through 10th and made your way around."

He recalled carefree summer days as a child and being gone for hours, playing with friends and riding his bike.

"There was no parental organized activities," he said. "As kids, we did our own thing. We played kick the can, hide and seek, cowboys and Indians, baseball during the summer, flew kites."

The "dunes" were a particular attraction.

"Where Sahara Avenue and Maryland Parkway are now, there were these artesian wells that flowed to the surface, as they did in many parts of the valley," he said. "We'd spend hours there."

Radio programs provided entertainment at night. Walter Winchell delivered the news, greeting America and "all the ships at sea." World War II meant rationing, and it wasn't until after the war ended that the Bryan family got a telephone.

"When the Huntridge Theater opened in October of 1944, that was a big, big deal," he said. "The kids attended the matinee every Saturday. It opened with a cartoon, typically The Three Stooges, then a Western, always a serial."

He said the downtown area had a small-town mentality.

"All the kids were aware that if you were misbehaving, chances were, one of the neighbors who observed you would tell your parents," he said.

The Last Frontier had an Easter egg hunt each year. All the kids in his class attended.

In the days before credit cards, local businesses would allow well-respected residents to "charge" things at checkout and send a bill in the mail. Bryan's father was a prominent attorney, so he had a Standard Oil account.

The hotels had "city ledger" accounts. If a family had such an account, the family was allowed pool privileges.

"That was to die for," he said. "But by the time I was in high school, that had ended because the town was getting big."

75-YEAR-OLD'S UNCLE HELPED BUILD

THOMAS & MACK CENTER

Michael Mack, 75, grew up at 10th Street and Charleston Boulevard. His uncle, Jerome Mack, would later lend his name to the Thomas & Mack Center at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

His father owned The Toggery on Fremont Street. It was a men's clothing store and supplied the police department with uniforms.

"A lot of people wore Western clothes in those days, every day," he said. "The town was really a very Western town."

At 13, he was driving the family's Plymouth, taking his dad to work and bringing the car back home. He said it was not thought to be remarkable at the time.

"Most of the kids were learning (to drive) at 13, 14, 15," he said. "(Although) you couldn't get a driver's license until you were 16."

The hot spot was Sill's Drive-In on the southwest corner of Charleston and Las Vegas boulevards (known as Fifth Street in those days). At Main Street and the Strip, near today's Stratosphere, the Round-Up Drive-In was another popular spot with carhop service.

The Wildcat Lair was a city-owned building near where The Mob Museum is now. It was a community center/club where teens went to play pingpong and games, dance and participate in activities.

It cost 14 cents for a movie at the Huntridge Theater, and a Coke was 5 cents. Kids wore Levi's and T-shirts all the time, and a lot of times they wore homemade clothes. As a teen, Mack and his friends went to the Last Frontier and the El Rancho Vegas, where they could rent horses by the hour.

" 'Don't turn them toward home,' that's what they'd always say," he recalled.

" 'Don't turn them toward home until you're ready to come home,' because they'd run, and you'd have to hang on."

Phone service meant sharing a party line. As soon as someone picked up the phone, an operator would ask, "What number?" Phone numbers were short. No. 823 was his dad's store, and Lucky cab was 711.

Anderson Dairy had a takeout counter for ice cream shakes. They were made in a metal container, said Mack, but it held more than the serving cup, "so they would let you tip it up and drink the (extra)."

When he was in high school, ranches were on the outside of town, about a half-mile west of Rancho Drive. Nothing was paved out there. The population was 24,624, according to the 1950 U.S. Census.

He graduated from Las Vegas High School in 1955 and has seen the town boom since then.

What does he miss most?

"The closeness, I guess, the camaraderie of families ... the way the neighbors got together, knew one another," he said.

BORN-AND-RAISED LAS VEGAN

RECALLS HAPPY CHILDHOOD

Pattie Stambaugh was born here in 1947 and recalled how the whole town turned out for Helldorado Days.

"It was the main hometown tradition; (everyone) in the valley came," she said. "In the '50s and '60s, when I was 10, 12, you went all three days, and my friends and I used to sell snow cones."

Stambaugh also marched in the Helldorado Parade when she was older and was proud to be part of the flutophone division.

She said people felt safe in their homes, and her family never locked its doors.

"When we'd go trick-or-treating, we'd go for blocks," she said. "You (could) go anywhere and not feel that anything was going to happen to (you)," she said. "It would just be my girlfriend and I, and we would be gone for hours on end. A lot of people would say, 'You have to entertain us if you want some candy,' so we'd begin singing or dancing or (do) something fun."

Their house was on 25th Street, now called Eastern Avenue. Stambaugh's father was an Elks Club member and was the Clark County auditor and recorder for 25 years. His position meant her parents knew all the local dignitaries and had encounters with stars of the day on occasion.

Like Richard Bryan, her family had pool privileges. One time, when she was about 12 or 13, her father took her to the Tropicana swimming pool, and she ended up swimming all afternoon with Jayne Mansfield's daughter, Jayne Marie Mansfield. Even though the movie star had recently given birth, she appeared perfect in her swimsuit, Stambaugh recalled.

Later, her older half-brother dated comedian Carol Burnett. Her older sister dated actor Lloyd Bridges, before he starred on "Sea Hunt."

Stambaugh recalled driving up and down Fremont Street, "just like in 'American Graffiti.' " It was "the" place to be seen.

Another recollection: The airport entrance was right off Las Vegas Boulevard, and people could walk onto the tarmac and used movable steps to board the planes.

"It's very interesting to watch 'Vegas' with Ralph Lamb because we knew Ralph Lamb. The family knew him," Stambaugh said. "It was a small community. The family knew everybody."

Contact Summerlin/Summerlin South View reporter Jan Hogan at jhogan@viewnews.com or 702-387-2949.