Video games, pizza arcades, and ending recidivism

Question: What do the iconic American companies Atari and Chuck E. Cheese have to do with turning criminals into productive citizens?

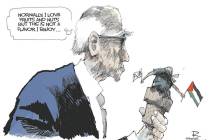

Answer: The man who founded those successful businesses — and emptied my pockets of more quarters than I could possibly count — is on the brink of a breakthrough to beat back recidivism. And Nolan Bushnell is making it happen in downtown Las Vegas, at the Larson Training Center.

Last week, I noted the tremendous success of the center since its opening in late 2013. In the past 12 months, of the 50 ex-felons who either graduated from the center’s 16-week program, completed the program but didn’t graduate or left after gaining enough skills to become employable, 43 have gained stable employment — an 86 percent success rate. Through Bushnell’s latest endeavor, a memorization and learning games project called BrainRush, and the efforts of Larson Director of Education Edward Bevilacqua and his staff, career criminals have become career-minded employees.

Better still, it’s happened without a dime of taxpayer money. But in order to expand, Larson has to find more funding sources. Rather than hit up a tapped-out state, though, Bevilacqua is confident that all he needs is a shove from the Nevada Department of Corrections to gain publicity and catch the eye of private foundations and other private-sector donors.

“We need the Department of Corrections to say, ‘We’re 100 percent behind this type of program,’” Bevilacqua said. “We don’t need government money to do this. This is a thing the private sector can do better.”

Brian Connett, Department of Corrections deputy director, certainly can’t argue with that statement, and he said his agency is fully on board with the Larson Training Center project.

“We’d like to be the cheerleaders who show this helps break the chain of recidivism, because we certainly want to see this expand, and do so at no cost to the taxpayers,” Connett said.

Public cheerleading can pave the path to the program’s continued prosperity.

“Now we go back to something tried and true, tapping into people who are successful,” Bevilacqua said. “Nolan Bushnell and companies like Google, and private foundations like the Engelstadt Family Foundation and the Salvation Army, people who have a vested interest in helping people coming out of prison not go back to prison.”

In fact, the project itself is headed to prison, gaining approval to launch a five-month pilot program within the Southern Desert Correctional Center, which will give soon-to-be-released inmates a head start.

“Having the school inside the prison is really the Holy Grail to breaking the chain of recidivism. If everybody who got out of prison knew how to type, their lives would automatically be better,” said Bevilacqua, noting that many people who drop out of the program do so because they have to commit their time to the larger concerns of food, clothing and shelter. Inmates have those issues covered. “It makes it a lot better. There are none of those hoops to jump through.”

Those hoops got Bevilacqua thinking about the population beyond ex-felons that could benefit from the Larson program, particularly the Las Vegas Valley’s homeless and destitute. He believes that operations such as Goodwill and Catholic Charities, if willing, would be ideal partners.

But for now, it’s about turning former prisoners into future producers who not only are no longer a drag on the economy, but who also become consumers of goods and services.

According to Bevilacqua, it costs $30,000 a year to house a Nevada prison inmate, and 80,000 people cycle through the Clark County Detention Center every year. Each of the CCDC’s 4,000 beds costs $1,000 per week to fill — a whopping $200 million per year. The recidivism rate in Nevada is around 30 percent, though that figure doesn’t include ex-cons who move to other states and end up in those prisons, or those who return to crime but aren’t caught. So total recidivism, Bevilacqua estimates, is probably closer to 60 percent.

Turning ex-cons into contributing citizens reduces all costs of recidivism.

“I think we not only look at the taxpayer cost, but the human cost,” said Bushnell, a wildly successful game-maker now looking to be a game-changer. “Let’s have productive citizens wherever we can get them. Let’s turn those tax consumers into taxpayers.”

A revolutionary yet simplistic idea indeed, from a man who knows all about revolutionary yet simplistic ideas. After all, he created Pong.

Patrick Everson is an editorial writer for the Las Vegas Review-Journal. Follow him on Twitter: @PatrickCEverson.