Peers explain what made Maddux smartest pitcher ever

We begin with a story because, well, there are so many:

Greg Maddux was pitching for the San Diego Padres in 2007 and found himself sitting next to teammate Chris Young during a game.

Maddux watched a batter swing at a pitch and offered this advice to Young: You’d better move or the next pitch is going to be a foul ball directly at your head.

Young laughed.

Maddux didn’t.

Young slid a few feet down the bench, and the next pitch was lined foul ... directly to the spot in the dugout where Young had been sitting.

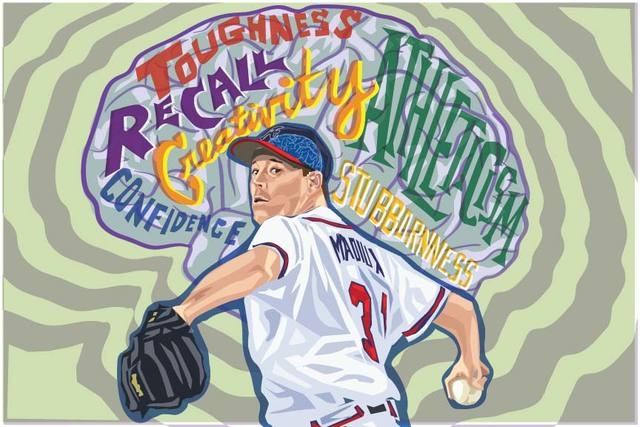

The brain is our most complex organ and close to our primary sensory organs for things such as vision and hearing and balance and taste and smell. Several types of memory are also implemented by it in distinct ways. Working memory. Episodic memory.

Motor skills learning.

You would think neuroscientists would savor a closer look at what goes on inside Maddux’s head. Talk about a magnificent learning tool.

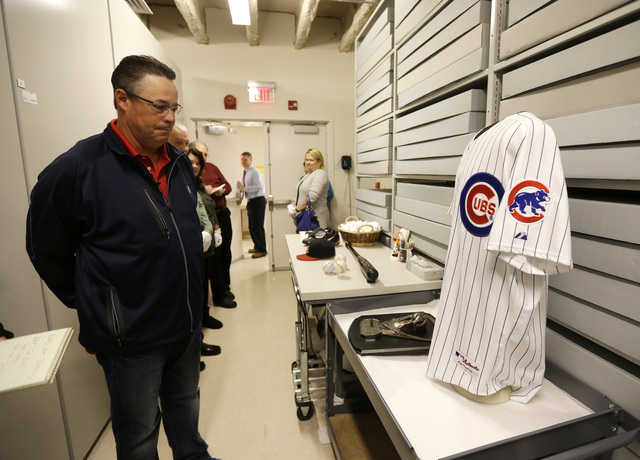

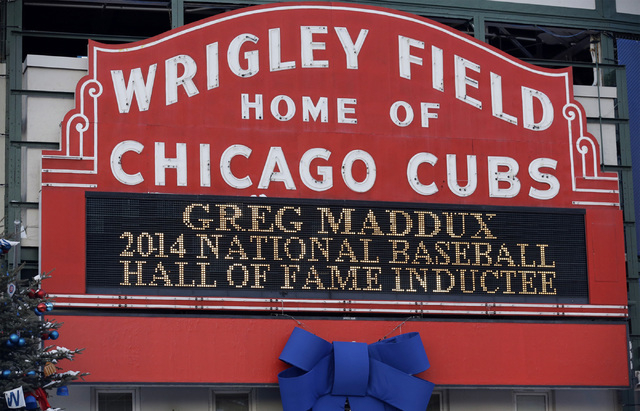

In a village in Otsego County, N.Y., at the junction of Routes 28 and 80, the National Baseball Hall of Fame will induct its 2014 class today, six new members set to assume their place as eternal fixtures for the study of the game’s history in the United States and beyond.

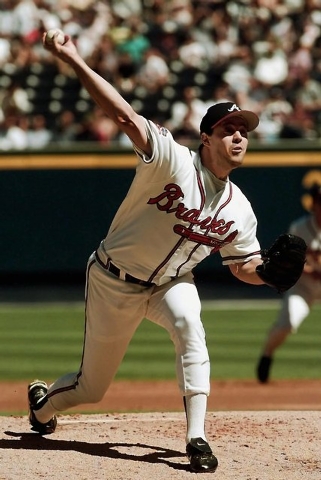

One of them happens to be the smartest pitcher ever to stand atop a white rubber slab measuring 6 inches front to back and 2 feet across, exactly 60 feet 6 inches from the rear point of home plate.

From where for 23 seasons, hitters tried to outthink Maddux.

From where they failed miserably.

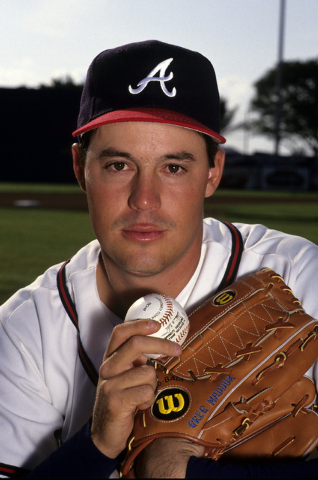

Cooperstown opens its doors to Maddux, now 48 and a Las Vegas resident and Valley High School alumnus whose ties to the city date to when his family moved here when he was a young boy.

That he was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility — Maddux received 97.2 percent of the vote — hardly drew a breath of astonishment from any points of the national map.

In a time when some voters shun anyone who competed in the Steroid Era, Maddux received the seventh-highest percentage in history. A shoo-in.

He won 355 career games, more in the live-ball era than anyone not named Warren Spahn. Maddux is the only pitcher to record more than 300 wins, 3,000 strikeouts and fewer than 1,000 walks. He was the first pitcher in history to win four consecutive Cy Young Awards (1992 to 1995) and is the only one to win at least 15 games in 17 straight seasons.

He won a major league-record 18 Gold Gloves and was a World Series champion in 1995 with Atlanta.

But hidden within those decades of pitching for the Cubs and Braves and Dodgers and Padres, within those years he dominated the game in Atlanta like few have for any franchise in baseball history, were constant signs of his mental gifts. No one thought the game better than Maddux. No one understood how to take advantage of its perplexing components more than he did.

It is why he could look at one swing of a hitter and then warn a teammate to slide down a bench or risk being plunked, why he made fools of some of the game’s greatest hitters with a fastball that averaged a pedestrian 84.3 mph, why he allowed just 0.6 home runs per nine innings pitched, why he produced more ground-ball outs than news about LeBron James does retweets.

Maddux wasn’t very big and wasn’t very strong and didn’t throw all that hard. But no one was tougher inside our most complex organ.

He also never has been much on talking, especially about himself and to those holding recorders.

Here, then, on the day Maddux walks through those hallowed doors at Cooperstown, are thoughts from those who knew him in different ways throughout his career.

Thoughts on what led to this historic placement among the game’s immortals.

Thoughts on The Brain of Greg Maddux.

THE PITCHING COACH

Leo Mazzone lost count of how many times this happened.

It could have been during a spring training game. Or a regular-season game. Or, yes, even a World Series game.

Maddux would allow a hit to an opposing player, walk back to the dugout, sit and look to his pitching coach:

“Well,” Maddux said, “he’s screwed the next time he comes up.”

It was his way of saying the same mistake would not be repeated. He wasn’t big on the law of averages, things evening out within a small sample. He expected more. He expected perfection.

There is a drill coaches use on young pitchers in which a home plate is colored to separate locations. The coach chooses a specific spot and the kid throws 20 pitches at it. A chart is kept of the number of times he hits it.

It wouldn’t be a fair fight to include Maddux in such a drill.

He might never miss.

“He would tell me, ‘Leo, I’m smart, but when you can command a fastball the way you want 80 percent of the time, that makes you really smart,’ ” Mazzone said. “That’s all he was about: command of his fastball, changing speeds and hitting his target better than anyone in baseball history. He never gave in. Ever. He never thought to waste pitches on an 0-2 count. That’s what separated mediocrity from greatness. His next pitch, no matter the count, was always intended to get the guy out.”

Maddux enjoyed his finest seasons when working under Mazzone in Atlanta from 1993 to 2003, but the pitcher’s consistency often would reach the point of tediousness.

So it went that a month or two would pass between Mazzone visiting Maddux at the mound during games.

“Greg would say, ‘Leo, come out and visit me in the sixth inning today. It gets lonely out there. The umpire won’t talk, and I’m tired of talking with (third baseman) Chipper (Jones), and I’m not sure (catcher) Eddie Perez understands a thing I’m saying.’

“So, I would go out there in the sixth and say, ‘How are things, Mad Dog?’ Mind you, he would be pitching a three-hit shutout. He would say, ‘Pretty good.’ I would nod and go back to sitting in the dugout. (Manager) Bobby Cox would look at me and say, ‘What did he say?’ I would say, ‘Not much.’

“Most guys have all the answers after the fact. Greg always had them before it.”

He also could be incredibly stubborn.

Maddux struggled against Luis Gonzalez, who hit .325 with 10 home runs in 135 plate appearances against him. Gonzalez played 18 seasons for six teams, but he was at his best with the Diamondbacks from 1999 to 2006.

It was during this time that Maddux spoke up in a certain pregame meeting: He told Cox that if Gonzalez came up with runners in scoring position and an open base, to go ahead and call for a walk.

It happened. Arizona had runners at second and third with two outs late in the game when Cox told Mazzone to go talk with Maddux and confirm the plan.

“I go out and say, ‘Here’s the guy you wanted to walk,’ ” Mazzone said. “Greg says, ‘Give me two pitches. If I fall behind 2-0, I’ll walk him. But I think I can pop him up to third in foul territory on the second pitch.’ Well, he throws a cutter above the hands on the second pitch, and Luis pops up to third in foul territory for the third out.

“Nobody compares to Greg when it came to thinking the game. I’ll never forget the last time he walked out of the clubhouse. I told him, ‘Mad Dog, you taught me a lot more than I ever taught you.’

“He looked back and said, ‘Yeah, but you gave me some good tips.’ ”

THE OPPOSING HITTER

It was at the 1996 All-Star Game in Philadelphia when Tony Gwynn found himself engaged in conversation with Maddux.

Gwynn mentioned how comfortable it must be for a pitcher knowing he had such a speedy and accomplished center fielder as then-Cleveland Indians star Kenny Lofton playing behind him, interesting when you consider Lofton signed with the Braves the following season.

“Greg says, ‘We have a young guy in our minor leagues right now named Andruw Jones who is just as good,’ ” Gwynn recalled in late March. “I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ Greg says, ‘I’m telling you, he’s unbelievable. You will see one day. Maybe then you won’t get as many cheap-ass hits off me.’

“I knew right then that I had got to him.”

The man who had as much success against Maddux as anyone died not three months after recounting such moments, when Gwynn on June 16 passed away from cancer at age 54.

He hit .415 in 94 at-bats with a .476 on-base percentage against Maddux. Gwynn, who spent his entire 20-year career with the Padres, never struck out against Maddux. Not once.

An interesting approach: Gwynn never guessed as to the next pitch he might see from Maddux. He never tried to outsmart the smartest guy on the diamond.

“I got almost 40 hits off him, and 20 were the ugliest I ever had,” Gwynn said. “I’d throw my bat out and flip a ball into left field or roll a ground ball between first and second. Every now and then, I would square one up. I knew that I frustrated him, but it’s not like I wore him out. I never felt like I was killing him.

“I never even felt comfortable facing him. It never mattered what the count was — 3-0, 2-1, 0-2. He was way ahead of his time when it came to reading swings and how best to attack the strike zone. I just tried to put a good swing on the ball against him and hoped it found a hole.”

Gwynn was most surprised about his early success against Maddux, when the latter played for the Cubs and one would have thought a ground-ball pitcher might have positive results against a nonpower hitter amid the grass at Wrigley Field.

But for whatever reason, Gwynn kept finding those holes, kept rolling those ground balls between first and second, kept piling up those “cheap-ass hits,” kept refusing to guess what the smartest guy on the diamond might throw next.

“I can’t wait until the Hall of Fame festivities,” Gwynn said in March. “At one table, you will have the 500 home run guys and at the other the 300-game winners, and then there will be me with all the Punch-and-Judy hitters. And then Maddux will come barging through the doors, and he’s going to look around and say, ‘I got that guy out and I got that guy out and that guy and so on.’ And he will deserve every minute of it. He is one of the big boys of our sport’s history.”

Sadly, Gwynn was gone before he could witness such a scene.

In an interview with The Washington Post in January, Maddux talked about how some hitters can pick up the difference on a ball’s spin during a pitch, able to identify release points or if a curveball starts with an upward hump.

But, he said, if a pitcher is able to consistently change speeds, every hitter is left helpless, limited only by his vision.

“Except,” Maddux said, “for that (expletive) Tony Gwynn.”

THE BEAT WRITER

Maddux played for the Padres in 2007 and 2008, a time when Tom Krasovic was in the midst of a 15-year run covering the team for the San Diego Union Tribune.

A pitcher was struggling during the ’07 season and sought counsel from Maddux, who began working with the young man in bullpen sessions.

“The kid would throw a really bad pitch, and Greg would tell him to throw it again, exactly the same way,” Krasovic said. “He would have him repeat bad pitches so his mind could feel what it was like each time he screwed up, so he could memorize all the bad things he was doing.

“Now, that sounds a little crazy. And for most, it’s an oddball way of teaching something. But that’s Greg Maddux. He just saw things differently from anyone else.”

He also saw things others didn’t.

Krasovic recalls a time when Maddux spoke about Jake Peavy during the latter’s Cy Young season in 2007, when Peavy went 19-6 with a 2.54 ERA and was as dominant as anyone in the game in a year’s time.

Maddux’s take: As terrific as Peavy was, he eventually would become frustrated over having so many of his pitches fouled off. Peavy had great velocity, which meant fewer and fewer balls were put in play.

It also meant his pitch count would run deep by the fifth or sixth inning.

“Maddux was the only one to mention it before it started happening,” Krasovic said. “And it happened. Peavy began to get very frustrated and not last deep into games because of all the foul balls. He was never the same after that season. It was just one of those weird wrinkles Maddux observed that no one else did. He had a different view of the world. He would have made a great detective in another life.

“Most of the time, you didn’t even realize he was around. But he would see and hear and observe everything. He took it all in. He missed nothing. As a (Hall of Fame voter), it was an honor to cast my ballot for him. It can be a headache, sifting through all the (Steroid Era) stuff when voting, but not with Greg. It was fun voting for him.”

Maddux signed a one-year deal with the Padres in December 2006, then offered a season in which he would win his 350th career game and 17th Gold Glove.

At his introductory news conference he walked past Krasovic, turned and said, “Hello, Tom.”

“I looked around to see if he was talking to someone else,” Krasovic said. “You have to understand that up until then, my only interaction with him was mostly during the playoffs as one of hundreds of reporters. The guy saw hundreds more during the course of any season. I had no idea he had any clue who I was. But his memory is incredible. He remembers everything.

“He’s a real-life Rain Man.”

THE MANAGER

Bobby Cox loved the pregame ritual in Atlanta that allowed him to shag balls at first base while his infielders took grounders.

But on those days Maddux wasn’t scheduled to pitch, he would get as much action at shortstop as anyone else during batting practice.

“I can’t even tell you how many throws I took from him,” Cox said. “He loved it. Loved the game. Loved being with the guys. Most general managers would look out there and say, ‘Get him off the damn field so he doesn’t get hurt. Don’t let him do that.’

“Not Greg. I let him do anything he wanted.”

Maddux came to the Braves during the winter of 1993, signing a five-year, $28 million deal. He had pitched the previous seven seasons for the Cubs, but his turn in the rotation rarely came up when opposing Atlanta.

Cox didn’t fully understand the level of player he had received.

Then came the first bullpen session of spring training.

“I had never seen anyone hit a target like he did,” Cox said. “It was incredible. I knew right then that we had someone very special.

“He was sneaky fast. His fastball was faster than it looked. He was so precise in everything he did, down to the second. He would tell me, ‘Any ball that remains in the air for at least seven seconds should always be caught.’ I’m not sure if he was kidding or not, but who would even think about that? He would always thank me for suggestions I made. I’m not sure I ever gave him any good ones.”

Cox has made his own trek today to Cooperstown, where he will join Maddux and former Braves pitcher Tom Glavine as part of the Hall of Fame class that includes onetime Las Vegas resident and former first baseman/designated hitter Frank Thomas and former managers Tony La Russa and Joe Torre.

It’s appropriate, three names that had so much to do with Atlanta’s success in the 1990s entering the Hall together.

“Every time Greg took the mound, I thought he was going to throw a shutout,” Cox said. “How much better a feeling could a manager have?”

THE TEAMMATE

John Smoltz is unique in this narrative: He’s one guy who actually watched Maddux struggle mightily at times.

Not on a baseball field.

On a golf course.

They might have spent as much time with each other in cars and playing 18 holes during their time with the Braves as they did in a clubhouse, pitchers who would reserve their tee times well ahead of Atlanta landing in any major league city.

“Greg is a completely different person playing golf,” said Smoltz, who in 2007 was cited having an 0.2 handicap. “He was a good golfer, but he would do things on a course that he would never do on the mound. He went through the shanks like all of us. I never saw him go through a bad funk pitching.

“Golf can be really humiliating. It’s a humbling sport. But he loved the challenge of it, of taking on the impossible. But on the mound, Greg was so precise. I really believe that if he wanted to, he could have gone an entire season without walking anyone.

“He maximized his ability without having to work. He was a master at never doing more than he needed and still getting the result he wanted. He got away with mistakes more than anyone because it was almost a shock to hitters when they saw a ball across the middle of the plate.”

Maddux was one of the all-time great pranksters, many of his tricks on teammates not suitable for print. But he was far from the studious professor in a clubhouse. His was a warped sense of humor, while his pranks often pushed the bounds of human decency.

And his teammates loved him for it.

“He was,” Smoltz said, “in a league of his own with that stuff.”

Smoltz would watch himself on video to try to correct any flaws a pitching appearance would display. He would need to see the outing a second and sometimes third time on film to pinpoint where things went wrong.

Maddux never did. He wasn’t big at all on film work. He had this unique quality to recognize a mistake fresh and immediately correct it.

“He understood the game better than anyone who has played it,” Smoltz said. “Those were great days ... a great time in our lives.”

THE BROTHER

There is this story — yeah, another one — about how Maddux would purposefully watch opponents as they stepped into the batter’s box and tapped the outside of the plate. He wanted to see how far the bat reached, essentially then knowing how much he could flirt with a spot so that the hitter couldn’t put a good swing on a specific pitch.

He was literally thinking in terms of an inch or two.

He embraced any advantage he could create, a mindset born during Wiffle ball games and afternoons of H-O-R-S-E on the basketball court or during a tennis match with his brother and friends.

“We were all 5 years older than him,” Mike Maddux said. “He had to play above his skills to hang with us, so he had to find ways to overcome not being as physically big. We’d handicap his score if we were playing basketball, or let him hit from second base during Home Run Derby. We both stunk at tennis.

“But when it came time to pick teams for baseball and we all put our hands on the bat to see who picked first, I would always take Greg. He was younger than everyone, but always a step ahead. He was the second-best basketball player in school, and the first was (former UNLV star) Freddie Banks. Greg was even a great bowler. He was good at pingpong. Anything where hand-eye coordination was important.”

Mike Maddux is the pitching coach for the Texas Rangers, a former major leaguer who spent 15 seasons with nine teams. His first game as a rookie for the Phillies came against Greg and the Cubs.

Greg won.

Their father was in the Air Force and stationed in Madrid for four years when the brothers were young, when they sometimes sharpened their arms by having rock-throwing contests over a fence on the base.

There weren’t enough kids to field a baseball team, so the Maddux boys would gather those willing bodies and make rules such as anything hit to right was a foul ball and the pitcher always had coverage responsibilities at second base. Anything to get a game going.

But things really changed when the family moved to Las Vegas in the mid-1970s. Greg was 10 and would tag along with Mike when he would receive weekly pitching lessons with former major league scout Ralph Meder.

One Sunday afternoon, Greg threw for Meder.

The scout’s impression: He had no idea how someone so young could have such perfect mechanics. He told Maddux not to change a thing, that he one day would be very special.

“He was just so much better than everyone else,” Mike Maddux said. “I remember a Little League game where he struck out 16 or 17 kids in six innings. The coach told him afterward, ‘We can’t pitch you anymore because nobody else gets to play.’ Greg was like Babe Ruth and Cy Young wrapped into one at that age.

“He always had good fortune, but he also made the most of it. He personifies the compliment of being an overachiever. He competed in school the same way. Whether it was a math or history problem, he figured out different ways from others to solve them. What he was able to do in his baseball career with his skill set is unbelievable. A lot of guys might have been bigger and stronger with better skill sets during his era, but they weren’t fit to wash his clothes.

“Obviously, him going into the Hall of Fame isn’t a shock. But it will be emotional for everyone. It’s a dream come true to watch this.

“Job well done.”

We have to end with a story, and it might be the best ever recounted about Maddux.

He was pitching for the Cubs when teammate Mark Grace noticed Maddux one game walking around the mound in a strained, uneasy manner. Grace jogged over to him, worried the team’s ace pitcher had injured his groin.

“He told me to stand in front of him,” Grace told reporters shortly after Maddux was elected into the Hall of Fame in January. “For lack of a better term, he was kind of aroused. Well, not kind of aroused. He was extremely aroused. I busted a gut right there.

“I said, ‘Dude, you really do love to pitch.’ ”

He really did.

And no one was smarter on that white rubber slab.

No one in history.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ed Graney can be reached at egraney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4618. He can be heard from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday through Friday on “Gridlock,” ESPN 1100 and 98.9 FM. Follow him on Twitter: @edgraney.