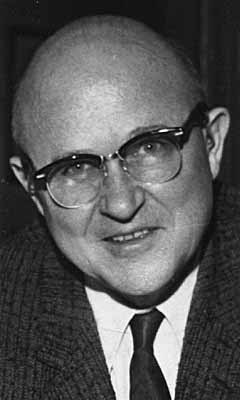

A.E. Cahlan

A.E. "Al" Cahlan came to Las Vegas as a schoolteacher, metamorphosed into a newspaper editor and within a few years dominated news media in Southern Nevada.

Between 1926 and 1960 he transformed a 300-circulation weekly into a daily boasting 27,000 subscribers, the largest in the state. The newspaper he built, now known as the Las Vegas Review-Journal, retains first position, and has a daily circulation of 151,162 and 213,619 on Sunday.

Cahlan became a political kingmaker and a civic progressive, using his newspaper and his influence to develop the community. And the editor-reporter team he hired -- his brother, John F. Cahlan, and John's eventual wife, Florence Lee Jones Cahlan -- were the most important scribes of their time in recording and preserving Southern Nevada's history.

Al Cahlan was born in 1899 and John in 1902 in Reno. Both attended the University of Nevada, where Al was one of three students who revived the school's sputtering student newspaper, "Sagebrush."

Both majored in electrical engineering but neither worked in the field. Maude Frazier, principal of Las Vegas High School, captured Al as a math and science teacher. But he worked summers with the Nevada Highway Department, which took him to Elko. There, the publisher of the Elko Free Press found out he had worked on a college newspaper and hired him on the spot.

John Cahlan also stumbled into journalism through his work, in 1919, as a play-by-play announcer at football games. "I'd run or walk up and down the sidelines. Through a megaphone I would tell the audience who carried the ball and how much yardage he made. When somebody was knocked out, I'd tell them who that was. Through that beginning came the regular announcing systems that they've got in the big stadiums now. I've never been able to find anybody else who would go back that far as an announcer. I think that I was the first one in the United States to do it."

Before home radios became common, many newspapers would "announce" the latest news bulletins received by telegraph, concerning events such as title fights and elections, to crowds gathered on the streets in front of their offices. Because he had developed a good announcing voice working a crowd with a megaphone, Reno's Nevada State Journal hired John to announce the World Series, then kept him on as sports editor.

In 1926 Frank Garside, a publisher who had operated newspapers in Tonopah and other mining boom towns, saw a similar opportunity in the news that a huge dam would be built near Las Vegas. He bought the Clark County Review, a struggling Las Vegas weekly, and brought in Al Cahlan to run it. Al Cahlan became his partner.

John Cahlan, who went to work for his brother and Garside in 1929, recalled, "We had the smallest office of a newspaper that I've ever seen. We had very few tools to work with. They gave me a four-legged table that had no drawers in it, no storage space or anything. They did put a typewriter on the desk ... but we had no direct connection with any news service."

John initially found the lack of resources depressing, but within a few months, he said, "I saw the chance that I could make the Review-Journal the best newspaper in the state ... I was the general roustabout ... I made the rounds of the community every day. And that is one reason that my expectations expanded, because I was talking to people who had the same idea that I had."

John talked Al into subscribing to a syndicate for editorial cartoons and some features; and about the time the paper went daily in 1929, a teletype wire service. "I was a very avid sports man, and I tried to make the sports stuff as good as that they could find anywhere," he recalled.

"Al would write the editorials, and he was the business manager, and he would sell ads." In January 1930 Al started writing "From Where I Sit," a column that appeared for nearly 40 years.

One of the frustrations of living in Nevada was several days of uncertainty as to who had really won elections. Returns were so slow from some Southern Nevada precincts, John Cahlan wrote, "There were times when a United States senatorial candidate had to wait for nearly a week before he could be certain that he could pack his bags and start the long journey back to Washington, D.C." Rural precincts didn't always bother to count votes the same day they were cast.

Al Cahlan thought this was no way to run a state. About 1928 he convinced the county commissioners to establish a policy that election officials were to stay at their posts on election eve until all votes were counted. "The commissioners were not happy to accept this program because the county coffers were not overflowing," wrote John Cahlan. "Hiring the extra personnel this required might mean that the road to Logandale would not be fixed." But the commissioners complied, grudgingly.

Al Cahlan then recruited some citizen in every precinct and got him to swear a blood oath that he would get the results to the newspaper that very night. Runners got to the nearest phone by bicycles, autos, pedestrian enterprise, even horseback. Precinct returns were added up in the newsroom by the entire staff of four or five, including advertising staff. Sometimes politicians themselves helped. Every hour a partial count would be posted on a blackboard outside the building, where political junkies gathered. Meanwhile, inside, John Cahlan would use the results to put out an extra edition.

In their low-budget way, the Cahlan team succeeded with surprising speed. Within five months of taking over the Review on May 1, 1926, they added another edition each week. In 1927 it became a tri-weekly and a daily in 1928.

The Las Vegas Age, run by C.P. "Pop" Squires, and the most important paper until that time, was quickly surpassed. In 1929 Cahlan and Garside bought out the Las Vegas Journal published by former Gov. James G. Scrugham.

Michael Green, a history teacher at the Community College of Southern Nevada, says the Cahlan-Garside team overwhelmed Scrugham and Squires with competence.

In a 1988 article for the Nevada Historical Society Journal, Green also asserted, "The Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal prospered because it was staunchly Democratic in a predominately Democratic city." And in the 1930s, when both the Nevada congressional delegation and the national administration became overwhelmingly Democratic, "it wires them into the national administration better." Being reared in Reno, when it was still the seat of power in Nevada, gave them contacts in state government. And Garside knew rural Nevada like his back yard.

"Pop Squires knew the ruling elite of Las Vegas just as well as they did," explained Green. "But his competitors were better connected to the world beyond Las Vegas."

Squires slanted his news coverage to favor Republicans and discredit Democrats. The Cahlans were better at keeping opinions and facts separate, and in any case Al was soon part of the power elite.

John Cahlan explained: "The power structure of Las Vegas in the '30s was headed by Ed W. Clark. Ed Clark was to Las Vegas what George Wingfield was to Reno. He controlled most of the economy of the community through his banking facilities ... Ed usually chose who he wanted as members of the city commission and county commission and those powerful bodies ...

"When Al came down here to run the newspaper, he became very close to Ed Clark; Al was his lieutenant, I would say. Al controlled the American Legion because he was state commander and quite active in the post here. Between the two of them, they pretty well controlled the politics of the community."

Clark was Democratic national committeeman for Nevada. "At the time of Ed's death, Al became national committeeman and followed more or less Ed's ideas. I think that you can say that Ed Clark and Al Cahlan were the two most powerful people in the 1930s and early '40s," said John Cahlan.

Al Cahlan at various times represented Clark County in the Nevada Assembly, served on the Las Vegas Planning Commission and chaired it, served on the Colorado River Commission and helped engineer the deal by which the war industries at Henderson would be bought from the federal government and kept open in private hands.

The Cahlans were community boosters and proud of it; they would point out community shortcomings, but their main job, they felt, was to point out the silver opportunity lining every civic cloud, and back any idea that would turn it into gold.

The late Ed Oncken, himself a longtime Las Vegas journalist, wrote about one instance. "In 1929 Las Vegas experienced its first boom in history, when Congress passed the Boulder Dam bill. The immediate influx of population and new business had neglected to find out that money to carry out the great project had not yet been appropriated.

"For six months the Review kept the town alive by propaganda, seizing any type of optimistic news to cheer up hard-pressed merchants, who were doing no business."

Even after the dam started, the economic boom did not feed everybody who wanted to participate. Hobo jungles sprang up around town; people with a few coins in their pockets were harassed on the streets by beggars. Like most cities, Las Vegas had vagrancy laws to suppress panhandling, but according to John Cahlan, Judge Frank McNamee was not enthusiastic about enforcing them. John Cahlan, however, was an alternate judge.

Whenever McNamee was out of town, said John, policemen would round up all the hoboes and take them to his court. Cahlan would explain to them, " You plead guilty, you get a suspended sentence of 10 days in the Blue Room. If you're out of town by sunrise, everything will be all right." Anybody who pleaded not guilty was apt to be found guilty anyway, but the sentence would not be suspended.

There were not many pleas of "not guilty," for the Blue Room -- Las Vegas' jail -- was infamous. "It had no plumbing fixtures at all. It had a floor that slanted into a big cesspool, and they'd wash it out maybe every two or three days. Anybody who was incarcerated more than a day or two never wanted to see it again.

"It was all one room, maybe 15 by 40," recalled John Cahlan. "It was made to accommodate maybe 10 or 12 people. On some weekends they'd have as many as 150 in there, and they would be from wall to wall, some of them sleeping on top of the others."

The jail was the only tool available to disperse all those people looking for work and not finding it. "If you haven't lived through it, you can't imagine what would happen to a little railroad community of 5,000 people having about a good 10,000 to 20,000 people dumped on it all at one time," John said.

As the dam neared completion, the Depression seemed determined to go on forever. The Cahlans got behind the Helldorado celebration, which was started in 1935 to develop Las Vegas tourism and replace the business that left with the construction crews.

As World War II loomed on the horizon the Army established an airfield here to train aerial machine gunners. But because not all of Congress believed war was inevitable, the effort was badly underfunded. The base didn't even have enough money to buy guns. Training for each gunner, explained John Cahlan, "started with BB guns, then .22s, then shotguns, and finally .50-caliber machine guns." Because the first three kinds were commonly owned by civilians, the Review-Journal started a successful drive to get locals to donate them.

About that same time Al Cahlan suffered a devastating blow to his political aspirations. Key Pittman, who represented Nevada in the Senate, died in office, a few days after his re-election in 1940. It fell to Gov. E.P. "Ted" Carville to appoint a successor. Al Cahlan had helped Carville get elected governor in 1938, and many say that Carville promised to appoint Cahlan as Pittman's successor. Instead, Carville appointed Berkeley Bunker, who had managed his campaign in Southern Nevada.

It cost Al Cahlan political power in a curious way. He walked away from it. Technically, he held the same leadership roles he held before; he would even achieve higher ones. But John Cahlan said, "He became disinterested, let's say. He wasn't as avid a Democrat as he was prior to that time. I can see why, because the Democratic party kicked him in the pants, and that was it."

In the long term, that kick would be costly to the Democrats. Chairman Clark was in his waning years and his political heir had been shown that party loyalty didn't always pay.

"As time went on Democrats who were business people became unhappy with the course that the Democratic Party was taking towards labor," said Al Cahlan's son, Forest Cahlan, an attorney who lives in Pahrump. Those became less active in the party and many eventually became independents or even Republicans. The long erosion of the Democrats' majority in Clark County had begun, accelerated with the breakup of the McCarran machine upon Sen. Pat McCarran's death in 1954, and continues today.

Al considered himself a newsman first, though. Don Digilio, who came to work at the Review-Journal in 1960 and eventually became editor, said, "Al actually wore a green eyeshade around the office. He wore suspenders, and garters around his shirtsleeves. This was in 1960, and I never knew anybody else in the news business who was still doing that."

Meanwhile, Al Cahlan and Garside had developed diverging views about the future of Las Vegas and its newspaper. "Al needed a new press," explained John Cahlan. "An eight-page press meant that we had to insert every time they had anything over eight pages, and that was costly. But Garside thought the town would blow away because Hoover Dam was already built ... he had been in so many communities where it was a boom and bust, and he thought Las Vegas was the same thing." He absolutely refused to invest the money for a new press.

Forest Cahlan says there was also a difference of opinion on how to deal with unions at the Review-Journal. "Garside said we keep the unions; Dad said that if we keep the unions, and give them what they want, we go under. The paper was making money, but not nearly enough to give the unions all the luxuries they expected."

Garside wouldn't sell his interest to Al Cahlan, but did agree to sell to a third party if Cahlan found one. Cahlan found Don Reynolds, a self-made newspaper tycoon, who bought Garside's controlling interest in 1949 and hired Al Cahlan to run the paper as general manager. However, Al Cahlan agreed to sell his stock to Reynolds at any time Reynolds chose.

The arrangement worked for more than a decade, during which the Review-Journal prospered. But in December 1960 with the circulation at approximately 27,000, Cahlan resigned, and Reynolds bought out his stock.

Al Cahlan turned his considerable energies to civic life and politics, ran unsuccessfully for county commission, and was associated with a printing company. He resumed writing his column, which was published by the Review-Journal's rival, the Las Vegas Sun. In 1968 he suffered a stroke and died three weeks later, at 69, in Southern Nevada Memorial Hospital.

John Cahlan stayed at the Review-Journal briefly as editor, long enough for Reynolds to find his replacement in Robert L. Brown, a former wire service reporter. John Cahlan built another career as an executive of the Southern Nevada Industrial Foundation and a lobbyist for the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce. He collaborated on a book with his wife and former star reporter, Florence Lee Jones Cahlan, on "Water: A History of Las Vegas." John Cahlan died in 1987 at the age of 85.

Nearly 13 years after replacing John Cahlan as editor, Brown would make his own play for the big time, buying a moribund North Las Vegas tri-weekly, the Valley Times, and turning it for a while into a third Las Vegas daily.

Brown paid Al Cahlan a high compliment when he described his editorial strategy: "I don't expect to be The New York Times. I want to be what Al Cahlan was."

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full