Former Review-Journal journalist enjoyed wild ride

It was July 19, 1966, and the national media were horse-laughing at Don Digilio, managing editor of the Las Vegas Review-Journal. Quoting the famous "reliable source," Digilio had reported on his front page that "Singer/actor Frank Sinatra and his youthful sweetheart, Mia Farrow, will be married at the Sands Hotel today at 5:30 p.m."

Chet Huntley and David Brinkley, co-hosts of NBC's flagship TV news show, were particularly scornful, mispronouncing Digilio's name while one snorted, "Doesn't he know Sinatra's in England and Mia Farrow's in Hollywood?"

But in Las Vegas, news competitors weren't laughing; they were scrambling to cover the wedding. They had been scooped too often when Digilio's exclusive but barely attributed reports proved true. And the lucky ones were there with cameras and notebooks that afternoon, as the 50-year-old Sinatra and his 21-year-old bride emerged from a private civil wedding in the entertainment director's office.

Huntley and Brinkley had enough class to mention, on the air the next day, that they were wrong and Digilio wasn't. He doesn't remember whether they pronounced his name right the second time.

It's pronounced "d'jill-e-o."

The Sinatra-Farrow scoop was only one of many Digilio broke during two decades with the Review-Journal:

•Cher's secret plan to dump her co-star and husband, Sonny Bono, then launch a solo career.

•The doings of mysterious billionaire Howard Hughes.

•Sinatra's sudden departure from his most famous haunt, the Sands, and the tantrum and fisticuffs that precipitated it.

Now 74 and retired, Digilio was Las Vegas' most readable journalist during most of the era when casino executives were assumed to be wiseguys and county commissioners were cowboys. Las Vegas was sprinkled with characters Elmore Leonard might have invented, had life itself failed to incubate them. Nobody covered them better than Digilio, for he was, to an extent, one of them.

Digilio was born in Omaha, Neb., where his father ran two cigar stores and pool halls.

"They did a little betting in those places at that time," Digilio noted recently. "The pool hall was the sideline. ... It had a couple of pool tables, and then a partition and a back room where you could bet on baseball, football, basketball.

"Even as I got older, I was never ashamed of my dad. He told me one time gambling would be legal all over the country, and he's not wrong. Although bookmaking, which has always been the most popular kind, still isn't everywhere."

Digilio graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1956. He served with the Eighth Army in post-war Korea, then was transferred to Tokyo where his duties were working for the military newspaper "Stars and Stripes" and playing baseball to entertain other troops. Upon discharge in 1958, he visited Las Vegas and saw a street edition of the Las Vegas Sun. Most newspapers hadn't used three-inch-tall headlines since the war, but the Sun in those days found a reason to use them nearly every night.

"I said this might be a fun place to work a couple of years," Digilio recalled.

He applied for a job at the Sun, and four days later he was working there.

His first big break came when police were sent to a domestic disturbance at the home of a fellow police officer. That officer had been thinking of exposing a burglary ring involving police officers, and some of the dirty cops knew he was thinking of it.

When some of them rolled up to his house, he surmised the unexpected visit was really a mission to kill him, so a gunfight broke out. After the lone-wolf cop recovered from wounds, he called Digilio and spilled his story.

By that time Digilio was working for the bigger and better-paying Review-Journal.

Digilio recalled the cop "had this little black book with dates and times in it, and they coincided with the dates and times of police reports. ... I would just day by day write another story about what burglary took place, who was involved. Several policemen were fired, and the chief resigned, and the city manager resigned."

Neither was involved in the crime ring, nor were most police officers, but the two brass felt disgraced it had operated under their noses.

A grand jury investigator demanded to know Digilio's sources, and Digilio refused, despite the threat of jail.

Digilio pointed out that the story didn't require any investigation on his part, yet gave him a reputation for breaking big stories and protecting his sources absolutely. That brought more tips. As he successfully followed up some, he was able to perpetuate that reputation.

It also helped, Digilio said, that so many former residents of his hometown had become involved in the growing legal gambling industry.

"There was Jackie Gaughan of the Four Queens, Benny Goffstein at the Riviera. ... All the big-time gambling places had Omaha people, and they knew me as a kid when they were running these gambling places in Omaha. My friends and I would go in and bet on the Yankees or the Red Sox, maybe just a $2 bet. And they knew my father."

When a gambling man needed to talk, Vincent Digilio's kid was who he talked to.

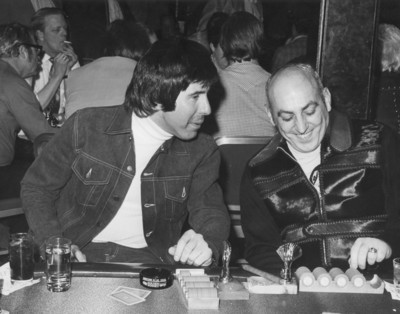

Lem Banker, a now-famous professional sports bettor who became a close friend, said Digilio's greatest advantage as a journalist was personally knowing big shots who other reporters merely knew to exist. "He would sit at a health club with Sonny Liston or Kirk Kerkorian or somebody like that, shooting the breeze in the steam room with their clothes off."

Digilio is an urbane man, whose home is full of art and hardbound books. Ralph Lamb, former sheriff of Clark County, is literally an ex-cowboy who may receive visitors in a tack room smelling of oiled leather and saddle blankets. Yet they were famously close. Digilio was a trusted political adviser to Lamb, but the relationship was compartmentalized.

"We socialized only at lunch, never brought our families together, but we were friends," Digilio said.

He made friends with the famous, but wasn't star-struck. In 1961 he married Jeannine McColl, a beauty who had been Miss Nevada, and they have two daughters. Jim Seagrave, then a reporter but now vice president of advertising at The Orleans, recalls that Digilio made it a rule to eat dinner every night with Jeannine and the girls.

"Jack Anderson came to Las Vegas and he wanted to interview Don," Seagrave said. "Anderson was one of the most important journalists in America at the time, and most journalists would have killed for that opportunity, but Don said, 'I can't. I have to be home for dinner at 6.'"

When the Beatles visited Las Vegas in 1964, at the height of their pop explosion, Digilio wrote an advance column deriding the group.

"It was tongue-in-cheek but the kids didn't understand that," Digilio said. "The next day we get a letter to me, and it has a dagger drawn on it, with blood dripping off it."

Editor Bob Brown printed the letter, dagger and all. Then he told Digilio to write another column on the Beatles. Digilio chose to make that one anti-Beatles, too.

"We had to hire an extra girl to ... open all the mail. We ran two full pages of letters to the editor or to me about how much they hated me."

Brown milked the story for national publicity. He assigned Digilio to cover the concert, and arranged a police escort, which was needed more for the photo opportunity than any danger. The headline on Digilio's review was one word: "Bah!"

In the body he wrote, "There's no way I can say I didn't like the music because I didn't hear one blink. ... How's that for luck? However, I have heard one of their records, so I'd like to thank those screaming girls for drowning out music that would have made the afternoon very uncomfortable."

Soon Digilio looked out the window of his home to see teenage picketers.

"Parents would drive up to the house, let their kids out and they all had these signs," he said. "'Down with Digilio,' 'Ringo isn't the only one with a big nose,' et cetera. But it was all very orderly. I went out and talked to them."

Actually, Digilio said, he didn't have strong opinions one way or the other about the Beatles. He was just stirring hornets.

Even after being named managing editor of the paper in the late 1960s, Digilio continued to write a column several times a week. It was funny and usually satirical.

"He could poke fun at even the most hallowed targets and get away with it because it was so funny even the targets had to laugh," Seagrave said.

Most of them laughed, that is. Frank Sinatra didn't.

It started when Digilio expressed an opinion about Nancy Sinatra being hired as an opening act at the Las Vegas Hilton showroom, a huge and important venue, with only one hit ("These Boots Were Made For Walking") to her credit. "Then Frank Sinatra sent word that if I showed up for his show, he was going to walk off the stage."

The feud escalated from there. Digilio admitted, even in print, that he liked Sinatra's singing, but not the offstage behavior of the star and his entourage. At one time a message board facing the Strip bore a message, in lights, saying "Don Digilio says Frank Sinatra has that certain nothing."

It culminated after Sinatra quit his semipermanent contract with the Sands in a tantrum over gaming credit. Digilio broke the details with a story that began "Singer Tony Bennett left his heart in San Francisco and Frank Sinatra left his teeth -- at least two of them -- in Las Vegas.

"Sinatra parted company with both the Sands and his teeth Monday morning. ... It was Carl Cohen, vice president of the Sands, who finally halted Sinatra's wild weekend. The Sands executive bloodied the singer's nose and knocked his teeth out after Sinatra tipped a table over on him."

Sinatra moved to Caesars Palace. Some time later, William Weinberger, president of Caesars Palace, and Digilio's friend the sheriff, arranged a peace talk in Sinatra's dressing room. Sinatra said Italians shouldn't be picking on one other and asked for a cease-fire. Later, even though he had broken some of the most embarrassing stories of Sinatra's life, Digilio avoided contributing anything to Kitty Kelley's best-selling collection of those stories in "His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra."

Sinatra and his friends didn't threaten him, Digilio said, but others did. It generally wasn't a threat of death but of a parking lot punch out. Digilio worked out at a gym most of his life, and had been an amateur wrestler, but the muscles hang on a small frame and most of his would-be educators were taller, heavier and had longer reach.

Yet, though he claimed in his column to avoid confrontations by hiding in the ladies' room, he actually faced his enemies and nearly always backed them down.

"One guy was in my office getting more and more heated, and I could tell he was looking for physical contact," Digilio said. "So while we were talking I had the phone book, and I just tore it in half.

"This is not brute strength. There's a trick to it, and the phone book wasn't all that thick in those days. But he toned down his rhetoric right away. ... He left the office without us having to have any kind of scuffle."

As a manager, Digilio is remembered for an easy-going style that served well to insulate journalists from the paper's owner, Don Reynolds, who built a media empire but could be merciless when dealing with perceived incompetence or insubordination.

Mary Hausch, who succeeded Digilio as managing editor when he was promoted to editor, remembered Reynolds was so offended by some headline that he ordered Digilio to fire whoever wrote it.

"So Digilio went down to the personnel department, asked them for the name of somebody who had quit lately, and sent Reynolds word he'd fired that guy for writing the head," Hausch said.

Digilio promoted Hausch twice, naming her city editor and later managing editor, both in the 1970s when the industry still had few women in management.

He also mentored the early career of Sherman R. Frederick, now the Review-Journal's publisher and president of its parent corporation.

Digilio started the writing career of handicapper Banker.

"Lem wanted to do a handicapping column," Digilio recalled. "I said 'What's your experience?' He said, 'Professional gambler.' I said, 'Can you type?' He said, 'No.' I said, 'Can you spell? He said, 'Not too well.' I said, 'We're off to a bad start.'"

Yet, Banker could pick games, so Digilio personally edited Banker's handwritten copy, later turning that job over to Royce Feour, a respected sportswriter and editor.

With their skill at editing and his own skill at game-picking, Banker became a nationally recognized authority on sports betting.

Digilio's most controversial journalistic effort was a story that became known as "The Angel of Death episode."

Under his own byline, on March 13, 1980, Digilio ran a copyrighted story that began, "In this city of legal gambling, the most bizarre, grisly tale of illegal gambling is unfolding in the intensive care ward of Sunrise Hospital.

"According to reliable sources, certain staff members of the hospital's graveyard shift were making bets on what time a patient in the unit would die.

"In addition, authorities believe that in some cases patients clinging to life have been 'put to sleep' with the help of a sunrise staffer."

"Clark county District Attorney Bob Miller on Thursday confirmed an investigation is taking place, but declined further comment."

Some details in the Review-Journal's stories, however, were never confirmed. Authorities never publicly acknowledged that bets were really made about patient deaths. And while they raised questions about a number of deaths, only one person was indicted, in connection with one death.

A District Court judge dismissed that case for lack of evidence.

Some national publications accused the Review-Journal of sensationalism. However, other media, both local and national, for weeks followed the story Digilio had broken.

Digilio says now, "I have regretted that I rushed into the thing, but my source had always been 100 percent. I still think something was definitely taking place. ... The hospital laid off a bunch of people, and nobody ever sued us over this story. I would have liked to have another source, but who is that source going to be? Are you going to ask somebody else on the same floor are they doing it?"

A few months later, in July 1980, a Wall Street Journal story reported the efforts of Jay Sarno, who had created both Caesars Palace and Circus Circus, to launch "Grandissimo," a 6,000-room hotel that would have been twice the size of any other in the world at that time. Even 28 years later, the largest today is thought to be the Venetian, recently expanded to 7,000.

The story said that five persons, including Lamb and Digilio, were being offered options to buy stock in the new casino at 3 cents per share though it would be offered to the public at $5. Others had already purchased stock at cut rates, the story said.

One was identified as Jay Brown, a Las Vegas attorney closely associated with Harry Reid, then chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission and now majority leader of the U.S. Senate. Another was identified as attorney Oscar Goodman, then noted for defending organized crime figures but now mayor of Las Vegas.

Digilio defended his deal at the time, noting that the owner of the rival Las Vegas Sun, Hank Greenspun, owned stock in the Del Webb company, a major player in Nevada gaming in the 1970s.

And he still defended it recently, saying, "You ought to be able to invest in what you want. I think a person can be in another business unless it very obviously shows that he is using his one job to benefit his investments."

He said management had never questioned his interest in a bar, which gave free drinks to Review-Journal reporters, and a slot machine route, or the real estate investments that give him a comfortable living even today.

But management didn't buy his arguments, and terminated him. He landed on his feet as a hotel publicist, but not at the Grandissimo, which was never built. Later he would resurrect his newspaper column in both the Valley Times, owned by his former boss Brown, and the Las Vegas Sun.

Fully retired today, he misses the time when he proved it possible to know everyone who was anyone.

"If I didn't have both my daughters and my grandchildren living here now, I wouldn't either," he said.

But he does not miss being the high-profile player recognized everywhere for the bald pate and mischievous smile that headed his columns for more than two decades.

"I had my 15 minutes over and over," he said, "and I kind of enjoy not having to play any more."

Contact A.D. Hopkins at ahopkins @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0270.