Sentencing disparity

The U.S. Sentencing Commission is supposed to see to it that defendants receive uniform punishments for similar crimes.

And while the Constitution gives Congress itself little responsibility for setting criminal penalties -- domestic crime was supposed to be the concern of the states -- it, too, operates under a presumption that prison sentences should be reasonable and substantially equal.

For the past 20 years, both bodies have been failing miserably at meeting this standard in the "cocaine" theater of their "War on Drugs."

Although the rush experienced by drug users smoking cocaine processed into "crack" is reportedly more intense, the drug is chemically similar to cocaine consumed as a powder.

But Congress in the 1980s wrote into law a mandatory minimum five-year prison sentence for trafficking as little as 5 grams of crack cocaine -- while such a sentence is triggered only when a user or dealer of powdered cocaine is found in possession of 100 times as much.

Because more than 80 percent of federal defendants sentenced in crack cases are black, while just over a quarter of those convicted of powdered cocaine crimes last year were black, this has had a predictably unbalanced impact on the racial profile of America's prison population.

The Supreme Court weighed in Monday on a case that did not directly challenge those congressionally imposed sentencing guidelines, but did ask whether federal judges can consider the unequal impact of the "mandatory minimums" in issuing lighter sentences to crack defendants such as Derrick Kimbrough, a black veteran of the first Gulf War who was sentenced to only 15 years in prison when federal sentencing guidelines called for him to receive 19 to 22 years.

In a baby step toward restored sanity, the high court ruled 7-2 that the lighter sentence was "reasonable."

U.S. District Judge Reggie B. Walton of Washington, who served as a top drug policy adviser to the first President Bush, applauded the decision but called it a "minor fix" -- which is an understatement.

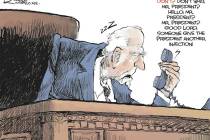

"Obviously the Supreme Court can't rewrite legislation and they can't rewrite the sentencing guidelines," explains Judge Walton, who once advocated harsher penalties for crack cocaine crimes but believes the current law has gone too far. "The ultimate fix has to be done by Congress."

But when Congress did nothing to end the segregation of public schools by race, the court threw out the entire machinery of school segregation, ruling that a de facto inequality of outcome trumped and invalidated any de jure assurance of "separate but equal."

It's too bad that the court lacked the will to make a similarly courageous statement, here.