Social networks must stand against censorship

The pressure for social networks to censor the content that appears on them just won’t cease, and the networks are bending. Censorship, however, is not what users want. Nor is it technically possible, even if the platforms won’t admit it.

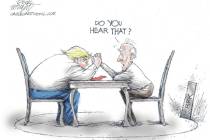

The European Union is pushing Facebook, Twitter and other social networks to comply with member states’ hate speech laws. In the United States, many in the media and on the losing side of the recent presidential campaign would like to see the platforms take action against fake news. Unlike in cases involving abuse of market dominance (the charge Google faces in Europe) or the release of users’ private data (over which Microsoft has fought the U.S. government), the platform owners aren’t fighting back.

In May, Facebook, Twitter, Google’s YouTube and Microsoft signed a code of conduct, in which they promised to review most hate speech reports within 24 hours and remove content that they find illegal. The EU wasn’t content with that; Justice Commissioner Vera Jourova voiced dismay this week that only 40 percent of reports are reviewed within 24 hours, according to a compliance audit.

Jourova’s tone was stringent. “If Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Microsoft want to convince me and the ministers that the non-legislative approach can work, they will have to act quickly and make a strong effort in the coming months.” This is a threat: Unless the social networks step up self-censorship, legislation will be passed to force them to comply.

In the United States, where speech is protected by the First Amendment, there’s no such urgency, but plenty willing to offer well-meaning advice. For the most part, demands have to do with having users flag offensive content and then reacting quickly to the complaints. That is a deeply flawed process, as Microsoft’s Kate Crawford and Cornell University’s Tarleton Gillespie explained in a 2014 paper:

“Disagreements about what is offensive or acceptable are inevitable when a diverse audience encounters shared cultural objects. From the providers’ point of view, these disagreements may be a nuisance, tacks under the tires of an otherwise smoothly running vehicle. But they are also vital public negotiations. Controversial examples can become opportunities for substantive public debate: Why is a gay kiss more inappropriate than a straight one? Where is the line drawn between an angry political statement and a call to violence? What are the aesthetic and political judgments brought to bear on an image of a naked body-when is it ‘artistic’ versus ‘offensive’?”

Flagging has been gamed ever since it became available to users. Campaigns have been run to flag pro-Muslim content on YouTube as terrorist, pro-Ukrainian content on Facebook as reprehensibly anti-Russian (and vice versa), gay groups as offensive to Christians and so on. In many cases, the social networks’ abuse teams have removed posts flagged by both sides so as not to alienate anyone. I see many of the bloggers I follow disappear for a few days due to bans imposed in such campaigns, then resurface and keep going until the abuse team is overwhelmed with new flags.

Still, regulators and well-wishers want the networks to make flagging easier and more prevalent — and then work as fast as possible with the complaints. The tech firms can comply only by hiring more censors, inventing technological solutions and going to third parties for validation. Facebook chief executive officer Mark Zuckerberg has said his company plans to use automation to take down offending content before users flag it and to work with outside organizations to verify stories. The EU-dictated code of conduct encourages the latter scenario, too.

Yet given the current, primitive state of natural language processing the automation will do more harm than good. A new gimmick — a shared database of content removed by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter and YouTube as terror-related — will only amplify the effect of errors made by each of the networks, and only until the posters start gaming it by making minor changes to their content.

As for outsourcing censorship, the partisan biases it brings into the process are too numerous to account for. A report from Morning Consult, a polling and research company, shows that 24 percent of Americans believe the reader holds the most responsibility for preventing the spread of fake news; just 17 percent believe the social networks do.

Indeed, a social network user is much better able to police her own feed than the network is to censor the staggering amount of content it carries. A reader is usually able to tell fake news from real news; in the Morning Consult survey, 55 percent of respondents said they had, on more than one occasion, started reading a story only to realize it was untrue. People have a social incentive not to share fake stories: They will be mocked by friends if they do. In many cases, people share fake news knowingly — because it confirms their biases or because they want to troll the subject of the fake story — but in these cases, Facebook and Twitter cannot expect a flag from these users, only from their equally emotional opponents. Reacting to such flags will often be a mistake.

Similar mechanics are involved in the spread of “hate speech,” terrorist recruitment videos and cyberbullying posts. It’s easy for a user to block those who spread this kind of content. Some won’t, however, because they’re not offended by it or because they’re interested in it for various, often legitimate, reasons.

Instead of signaling compliance, the social networks should stand up and make a few simple points.

If a government has passed laws against hate speech, it should be able to enforce them with the large security apparatus at its disposal. It cannot delegate the policing to companies any more than it can outsource, say, the fight against terror. If the governments admit they are unable to police the social networks, how can they expect the private firms to be able to do it? In any case, in the Morning Consult survey, only a small minority wanted the government to prevent the spread of fake news. That reflects the average user’s attitude toward any government-enforced censorship, no matter how it is exercised.

In a free society, specific people are responsible for their thoughts and actions. Social platforms can provide the tools for getting rid of offensive or irrelevant posts, and try to block bots, but they should not exercise some kind of misguided parental authority over their adult users.

The social networks may see taking a stand as an unnecessary risk given the legislative threats. Yet they may be better off fighting censorship now, before they’re choked by ever-increasing, unreasonable demands to step it up.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist.