Father wrote of Iwo Jima’s horrors in letters to family

Pam Brown doesn't remember much about her dad.

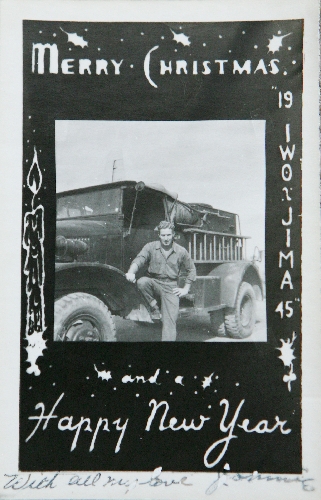

A sailor in the Pacific during World War II, he missed her birthdays and Christmas. And she missed him.

She recalls running away at 4 years old and wandering Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles with a Life magazine full of pictures of soldiers and sailors tucked under her arm.

"I was going to meet my daddy coming home from the war," she said.

Even that memory is vague.

Except her dad, Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class John E. Lee, wrote about it in one of hundreds of love letters he exchanged with his wife.

"I do hope she has lost her desire to run away from home," her father wrote two days before the first wave of Marines landed at Iwo Jima. A month after the battle ended, he wrote, "You can tell Pamie that I am not in a 'hoxhole' as she so cutely pronounces it."

Brown, 70, found more than the reflections of a homesick sailor in a trove of handwritten letters, now yellow with age as they lie scattered across the floor of her North Las Vegas home.

Lee had a "ringside seat" for the "bloodiest battle in history."

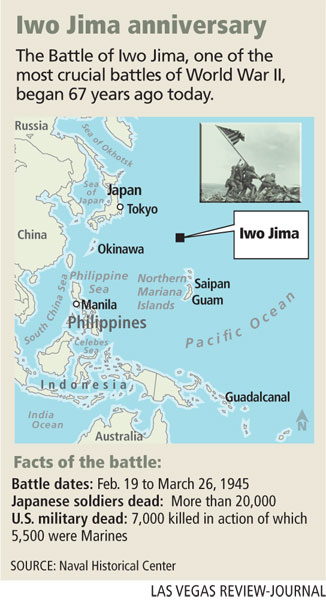

Today marks 67 years since thousands of Marines stormed the beaches of Iwo Jima, a sulfur-scented volcanic rock with three airstrips that became a steppingstone for U.S. bombers to reach Japan and eventually end the war. The Battle of Iwo Jima raged from Feb. 19 to March 26, 1945. About 27,000 men were killed, including 20,000 Japanese soldiers hiding in tunnels and burrowed in caves and pillboxes on the 8-square-mile, pork chop-shaped island.

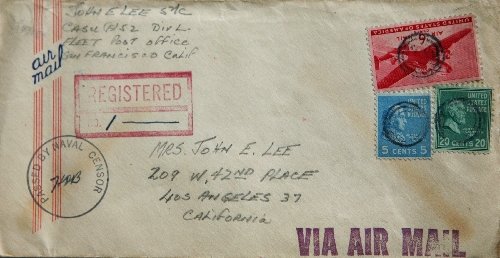

Brown said she "found a lot of history" in her father's letters. The vast majority had been previewed by military censors, who sometimes cut words or chunks from the Navy stationery before they sealed them in his pre-addressed envelopes and sent them by airmail to Mary Lee.

"I think the war movies, as graphic as they were, didn't portray it as realistic as it was," Brown said. "I don't think America was ready for the truth in the '40s."

ACROSS THE PACIFIC

In keeping with the loose-lips-sinks-ships mind-set, "Johnnie," as he always signed his letters, never mentioned the name of the vessel he was on that left the Hawaiian Islands at Pearl Harbor on Feb. 4.

"We were six merchant ships and five destroyer escorts," he wrote.

While Marines raised the second U.S. flag that flew over Mount Suribachi, as seen in the iconic photograph taken by Joe Rosenthal on Feb. 23, Lee was about to pen a letter to "My Most Precious Wife," letting her know he was still at sea but had gotten 16 letters in his first mail call. "And best of all, eight from you sweetheart. I have read and reread them so much I almost know them by heart."

His ship reached Iwo Jima on March 2 and was close enough for sailors to watch the battle waging.

"There were ships and warships blasting away, every type of vessel afloat there was -- the hospital ships painted white, the destroyers, the big powerful BB (battleship), the cruisers, etc. Room at the rail was at a premium and very crowded to say the least. Overhead the carrier planes were going on their rocket runs and the chatter of machine-gun fire -- on shore. There were tanks blasting away. We could see the flamethrowers working over a pillbox and the artillery positions taking up the fight."

It had rained all day on March 4. Lee's ship was anchored about 300 yards off Iwo Jima, the day Marines had secured one of the three airstrips for the first B-29 bomber to make an emergency landing.

"Yesterday, I was watching about a hundred Marines taking baths in the beach, probably their first bath in 10 or 12 days," he wrote to his "Darling Sweet Wife."

"Anyway the Japs were firing at them with rifles and the shells were hitting only about 10 yards from them! But it didn't seem to bother them. Today some more are bathing in the same part of the beach but there isn't any rifle fire. Either a plane or flamethrower got them," he said, describing a scene that was portrayed in the 2006 movie "Flags Of Our Fathers."

HITTING THE BEACH

Lee landed on Iwo Jima on March 7.

"We were marked up to be sent in on the third wave to hit the beach at Iroquois. I had shot my carbine just 45 times. Boy, were we trained men, ha ha," he wrote in one dispatch.

Later he described the assault.

"We were told that we would go ashore at 1300. We ate early chow and got ready to storm the beach -- Commando Lee! About 12 noon one of our corpsman came aboard to get some plasma and he just about looked like a ghost. He was red-eyed, unshaven, looked so darn tired. He said, 'Boy things are bad.' ... Well, I got so darn scared I just about wet my pants.

"For the first time I really woke up to the fact that there was death on that black piece of sand."

They hit the beach not knowing what to expect, only to realize that no one knew where their unit was located.

"They loaded us up into a Marine truck and started out. We rode and rode. We passed through the different camps and then up a road we passed some tanks and then I see a lot of Marines in foxholes. Well, I thought, 'If those Marines are in foxholes, what the hell are we doing riding around in this truck like a bunch of Sunday drivers up Wilshire Boulevard?'

"So I hollered at the driver if he knew where he was going and he said he was lost. Boy did we ever get out of that place. We found out later that we'd been about a mile inside Jap lines, and to this day I don't know why we weren't all killed."

They eventually found their camp about one-quarter mile from the 5th Marine hospital and cemetery, near the edge of the main airstrip, "so I saw a lot of horrors of this battle. It was terrible."

DIGGING IN

There's an eight-day gap in his letters until March 12, when he writes one from his foxhole:

"Beze and I are dug in together. We have a foxhole 4½-by-8 feet and about 3 feet deep. You know, just like a couple of moles! We crawl in our hole at dark and stay there until daylight. ... In a few weeks we will be able to come out of the holes and live in tents. For that I will be thankful. We are eating K-rations and anything else we can steal from the Army or Marines. We get two canteens of water a day and if there is any left over, Beze and I have a can we save it in. Then after a week we use that water for a bath."

Lee then acknowledges receiving a letter from his wife, writing, "I am glad to know that Pamie is being a good girl and helping mother around the house. Also glad to know she hasn't forgotten her daddy. ... I pray that this mess will soon be over and all the men in the service can return to their families again and live like human beings. With all my love, Johnnie."

On March 14, he wrote to "My Most Precious Ones," from "Somewhere in the Western Pacific."

"We are somewhat restricted as to what we can write. ... I can't write as yet just where we are but can say that we have been under combat. The Japs have used mortars, machine guns and sniper firing, rockets, etc. against us -- all of which rocks one to sleep at night. ... We are also getting a hot meal at night, which is most welcome after eating K-rations. I don't mind the K-rations except for the crackers in them. They are so darn hard that I almost break my teeth."

CELEBRATING THE NEWS

By March 19, word had reached Iwo Jima through radio broadcasts that the last German troops on the Ruhr River had surrendered, and the war in Europe would soon be over.

"Last night about 8 p.m., all hell broke loose around here, flares, carbines, revolvers, pistols machine guns. ... There was a lot of ammo in the air. I couldn't get excited over the deal because I wanted it to be confirmed officially.

"I was at the transportation shack when all the fireworks started, so when the alert came I came home to go to bed. I brushed the dirt off my sack and as I did I knocked something on the deck. I picked it up and to my amazement it was a .38 slug. There was a hole in the top of our tent! I was glad I wasn't in my sack, as I might have had a good size pimple on my fannie."

On March 21, Lee told his "sweetheart, I miss you something awful. Let's hope and pray that this terrible mess will be over before long and all the families of the world can be reunited."

Two days later he was surprised when one of the pilots gave him some corn-on-the-cob roasting ears. "He flew it in from some place. It's a certainty that it wasn't grown here. Nothing grows here but sand crabs and flies. This is the hellhole of creation."

BANZAI ATTACK

In desperation, Japanese Imperial Army soldiers pulled a "banzai" attack in his area the day before the battle ended. "The toll of our men I don't know, but the Japs lost 198 out of 198 and did those Marines ever tear them up," Lee recalled months later in an uncensored letter.

He wrote his "darling wife and babies" on March 27, one day after the Battle of Iwo Jima , to let them know he was all right after the Japanese banzai attack.

"The raid put the fear of God into all of us, but I think we have the safest encampment of any other outfit on the island. ... Last night the five of us in our tent slept with our heads around the center pole just in case anyone wanted to slash the tent, they would trim our toenails and not our throats!"

On March 28, Lee and his buddies at the motor pool had a feast with a 2-pound can of sliced bacon they got from the Marines and 2 pounds of Vienna sausage.

"We had the cheese out of our K-rations, and Purcell and I contributed a couple loafs of bread that a pilot gave us. We brought a blowtorch down from the garage and fried things up nice.

"All of this was topped off with lemonade and a chocolate bar. Now I need a toothpick and a big black cigar. All the comforts of home."

Lee, who patched up bullet holes in warplanes and kept trucks and jeeps rolling, made a generous friend in one pilot. He "gave me a Jap knife that he took off a Jap the Marines had found up in the hills," Lee wrote on April 7. "Seems as though I had fixed his jeep a week or so ago and he remembered me.

"It's very seldom that you find fellows like that. I had a few souvenirs like Jap money, Jap hand grenade, an ashtray that I made out of some empty shells. There are a few Jap flags but they are selling for $100 up, mostly up.

"But I'm content with what I have, and the best souvenir of all will be my two dog tags around my neck when I hit the states."

Nine months would pass before his honorable discharge in Shoemaker, Calif., on Feb. 8, 1946, and Lee collected his final pay, $94.52, a significant raise over the $24 he earned for two months pay as a seaman first class.

AFTER THE BATTLE

In that span at the end of the war, he witnessed more history at Iwo Jima and learned about a catastrophic new bomb.

On Aug. 5, 1945, the day before the B-29 Enola Gay dropped the "Little Boy" atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, Lee got to see the world premiere of "Week-end at the Waldorf," starring Lana Turner and Ginger Rogers.

"Imagine on Iwo Jima of all places! There was the usual popping of flash bulbs that go with such an occasion, but from where I sat I couldn't tell just who they were snapping. That Turner is quite some gal. ... And Ginger! Ah Ginger. She was her usual self and good, natural. ... As a prelude to the feature we also had a short, 'From the Shores of Iwo Jima.'

"It was in color and very interesting. Is this the one you saw? In one spot where they were shelling at night with the field pieces, I could almost see my foxhole. You see, I was dug in about 10 yards from the guns, and every time they fired that's what made the sand get in our socks. Boy was that some life! Life on Iwo is much better but it's still a hellhole -- it always will be -- no matter how they change it. Forever yours."

ATOMIC ENDING

In the days that followed the first atomic bombing, Lee feared the Japanese would retaliate.

"Boy this atomic bomb has certainly got the world in an uproar," he wrote on Aug. 8. "Every time the news comes on the radio, guys crowd around the radios 10 deep to hear the latest reports. ... I can just see the headlines in the papers at home telling about the bomb and effects. Maybe they should take the bomb, its manufacturing equipment and ship them out to sea and sink them all together. It will surely bring the war to an early end -- I hope."

After the B-29 Bockscar unleashed the "Fat Man" bomb over Nagasaki, Japan, on Aug. 9, Lee wrote that same day that "this new atomic bomb is certainly something."

"A lot of fellows are making bets on the date of VJ. I hope it will be soon. It all hinges on just how stupid the Jap warlords prove themselves to be," he wrote. "I believe if it were left up to the people of Japan the war would be over now. ... Let's hope that the nips don't try gas as a retaliation measure for the atomic bomb."

At 8:30 p.m. on Aug. 15, Lee wrote about the end of the war.

"Well today the world is happy. Truman made his little speech and the war is over. Or is it? For some reason the news wasn't too exciting. I suppose it is because we had to sweat it out for so long. ... Iwo looks the same in peace as in war. There wasn't a celebration here to mark the end of the war. Other outfits got the day off but not us. Although we did get two free beers!"

By Jan. 3, 1946, Lee had left his fears behind at Iwo Jima and had sailed back to Pearl Harbor for "G.H. Day," aka "Going Home Day."

"The surf is rather rough today and it's cold and windy," he wrote. "Don't think it hasn't been the longest 14 months in the history of time. The lonesomeness and boredom will soon be over. This is official. I'm leaving so you can believe it now. With all my love, Johnnie. See you soon."

BACK IN THE STATES

Lee had survived the war and for a few more years would enjoy the comfort of his family.

"When he got home I remember great weekends going fishing up near Crestline. I remember going to his ball games. He always loved whatever (his son) Tom and I were doing. He would come out and ride bikes. I think he was religious in his beliefs," Brown said about her dad, a personable, sandy blond man with only a high school education.

Then the fun stopped in the summer of 1951.

At age 32, John Elmer Lee, a Los Angeles firefighter, was driving back from taking his captain's exam. They were supposed to go swimming at Hansen Dam after she had watered the lemon trees in the backyard -- his pride and joy. He never came home. A drunken driver swerved over the centerline on Riverside Drive and killed him in a head-on collision.

"For years I felt God killed my father because I forgot to water the lemon trees. I was so mad at God. That's how I felt at 9 years old," Brown said.

Her mom, Mary, remarried two years later. She died in 1993, living the last part of her life in Oregon.

"My mother married two good men. Most people would be lucky to have one love of their life and she had two."

LETTERS OF DISCOVERY

Brown learned a lot from her father's World War II letters.

"I discovered my dad from reading these letters. And I discovered myself or part of me from reading these letters," said Brown, who moved to the Las Vegas Valley in 2000 to be with her daughter, Stephanie Sevilla.

"He was very, very in love with my mother," Brown said. "He had a great sense of humor and was opinionated on how the war was being led.

"When reading these letters, I realized how much he sacrificed for 18 months doing what he believed was right and what he had to do."

Like her father, she is patriotic.

"I've always been patriotic and maybe it's from this. Anyone in service is risking the ultimate sacrifice. I don't think my generation when it came to Vietnam had that patriotism. I don't think I had it until I became older. But I learned from my dad that you may not agree with your government, but it's still the best country and you should support it."

And Lee was down to earth.

"He wasn't a hero. He was an everyday man doing what he believed for the betterment of his country."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.