Boy’s killing near Nevada border remains unsolved after 30 years

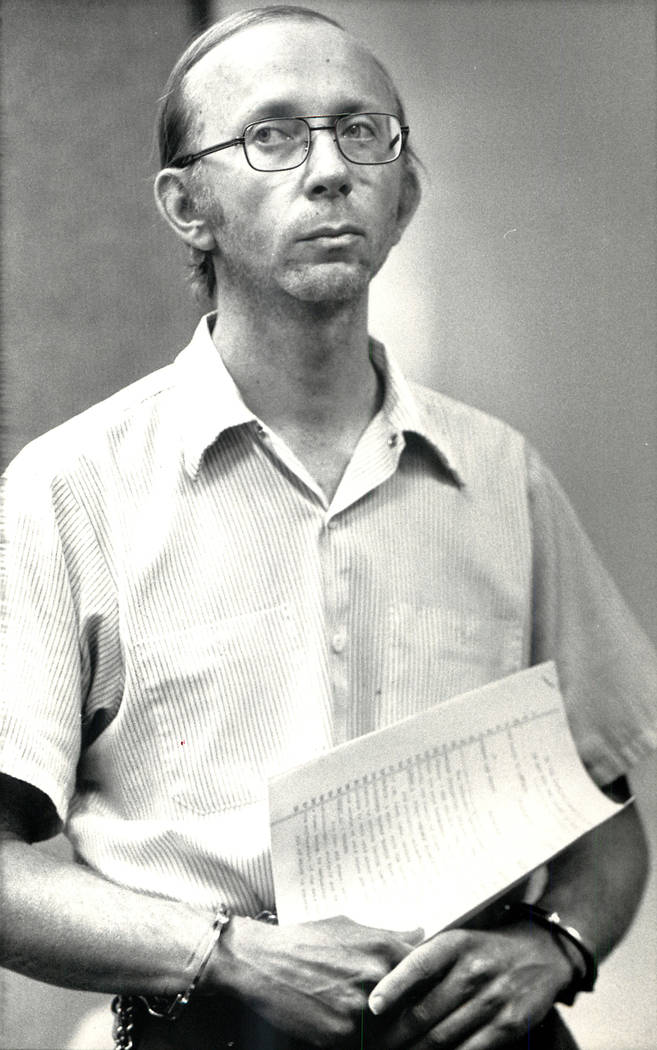

A murder accusation threw Howard Lee Haupt into the media spotlight three decades ago and turned his life upside down.

He was arrested and tried on a murder charge in the death of 7-year-old Alexander Harris. And though he was acquitted, Haupt says the ordeal has stayed with him.

“I’m still stuck in the same (expletive) that I always was,” he said in a September phone interview.

Haupt, now 66 and retired, was accused of leading the boy out of an arcade at Whiskey Pete’s in Primm and killing him. Today marks 30 years since the boy was kidnapped.

Then a San Diego computer analyst, Haupt endured a highly publicized trial rife with odd twists — conflicting eyewitness accounts of the abduction, a memory expert, a bug expert who questioned the boy’s time of death and a Haupt lookalike who reportedly punched a defense attorney by the courthouse snack bar after cross-examination.

Between the prosecution and the defense, about 100 witnesses were called to the stand, according to news reports, and jurors sifted through more than 250 pieces of evidence.

But after Haupt was exonerated, no one else was charged. Police still don’t know who killed the boy.

The crime

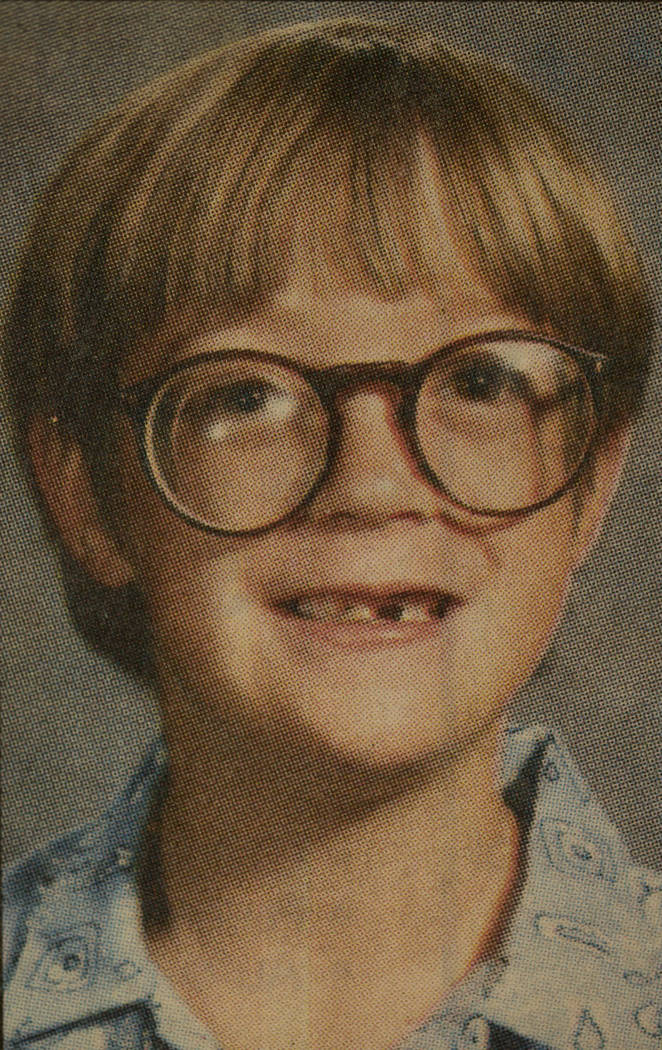

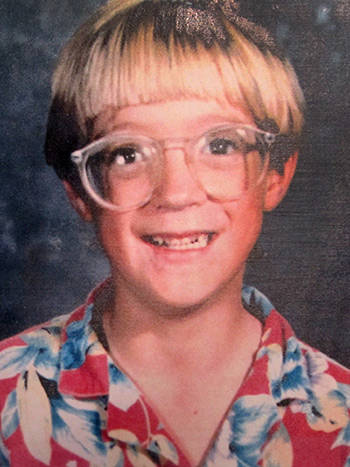

The case traces back to Nov. 27, 1987, when witnesses told authorities they saw a man resembling Haupt lead Alexander from the arcade just before 11 a.m.

Alexander was with his family on Thanksgiving weekend when they stopped at the hotel-casino on their way back home to Mountain View, California, after a trip to Las Vegas. It was the last time anyone saw the boy alive.

Police quickly ruled out family members as possible suspects.

Haupt had a room at Whiskey Pete’s at the same time Alexander disappeared, but he denied being in the video arcade the day of the abduction. Haupt said he was with a friend when the boy was last seen.

A gardener found the boy’s body under a trailer near the hotel 33 days later with no visible trauma. Investigators concluded he was suffocated.

Haupt was arrested on Feb. 19, 1988, in connection with Alexander’s murder. He was working at his Southern California office when Metropolitan Police Department investigators and FBI agents insisted he go in for questioning.

“They spent the next three or four hours trying to make me confess to something I didn’t do,” Haupt told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in September.

Law enforcement officials held him in the San Diego County jail before they put him on a plane to Las Vegas at the end of February 1988. Police had him lie flat in the back of an unmarked patrol car with a jacket over his face to shield him from news photographers as they took him to the Clark County Detention Center.

Haupt said he struggled with navigating the five-week murder trial that began in January 1989 in Las Vegas.

“You’re just part of the package,” he said. “Part of the show.”

And that show brought intense media coverage, which he likened to a “hostage situation.” The story was above the fold in newspapers and led every newscast, every day.

Haupts said the attention was so overwhelming that he feared being in public.

Courtroom drama

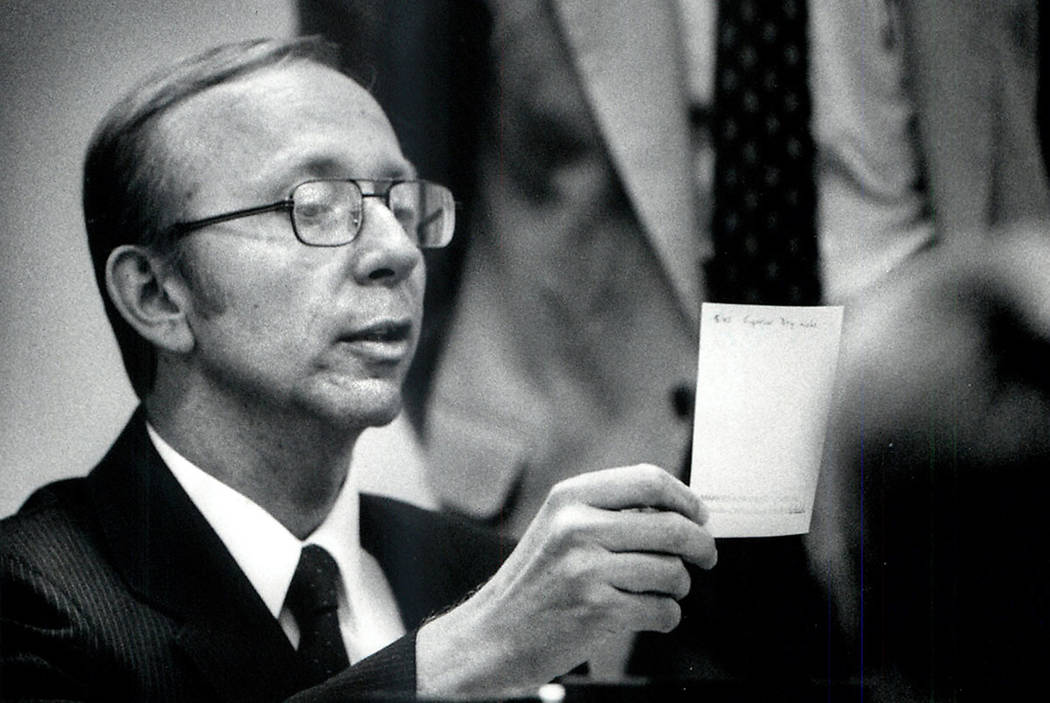

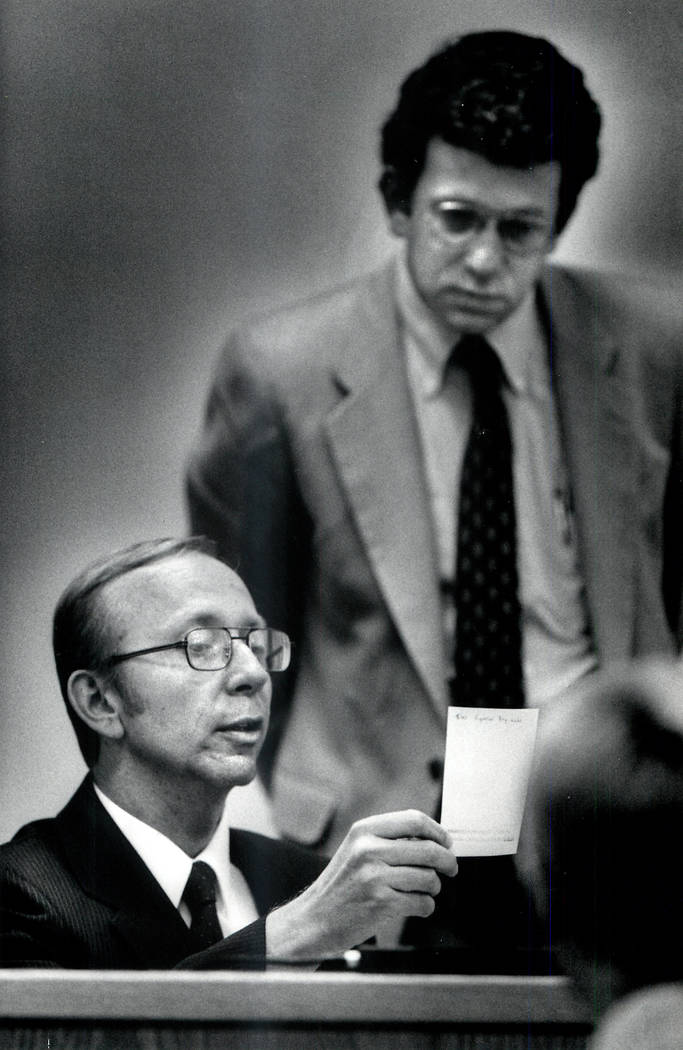

As the trial was winding down, prosecutor Mel Harmon had an angry outburst in a closed-door meeting with District Judge Stephen Huffaker, pleading with him not to instruct jurors to acquit Haupt.

Tom Dillard, a now-retired homicide detective who spearheaded the investigation for Metro, lost a week of pay after he made an intimidating call to Huffaker, during which he reportedly told the judge the jury instruction would be “ridiculous.”

The judge didn’t deliver the instruction, but jurors at the time said the conflicting eyewitness accounts led them to find Haupt not guilty. Haupt trembled and wept on his attorney’s shoulder as the verdicts were read, according to news stories.

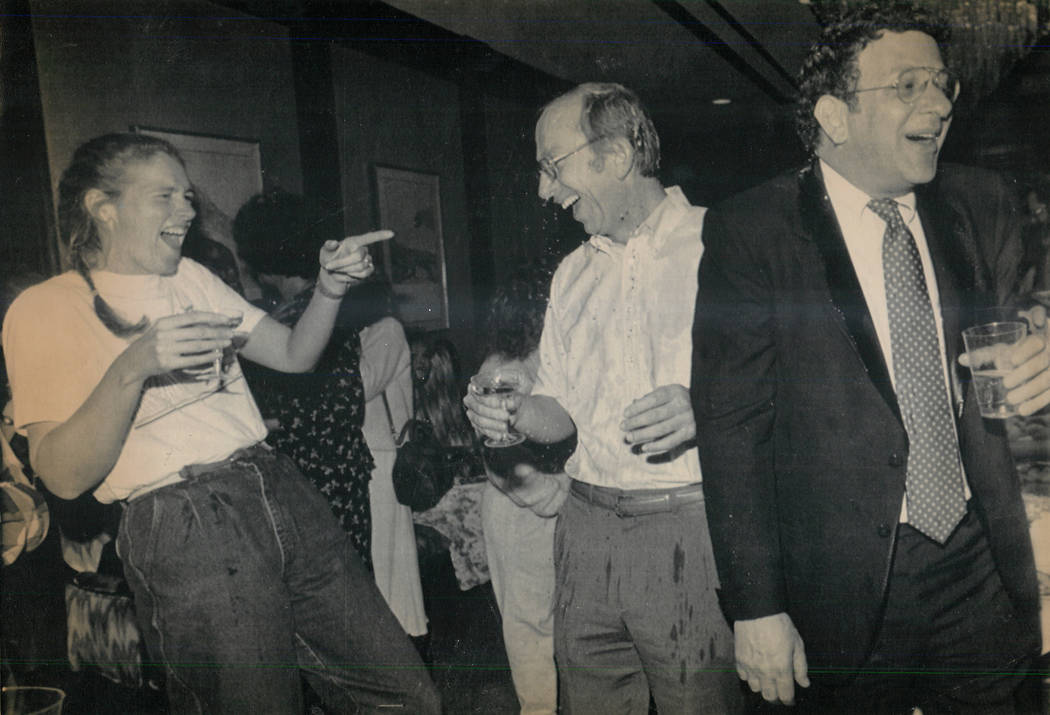

He later was showered with champagne during a party celebrating his acquittal, newspaper photos show.

“I’m sure they (the jurors) did their best as I did,” Harmon told the Review-Journal in 1989. “I accept their verdict. This is the opinion of the 12 people who were chosen to give their opinions. That’s really all it means.”

Harmon, now retired, said in a recent phone interview that he questioned whether jurors were able to come to their conclusion in a just way. He said jurors were not sequestered and may have been exposed to newspaper articles about the judge’s plans to issue an instruction to acquit Haupt, which could have influenced their decision.

“What stuck with me was not guilt or innocence, but I felt that the judge made himself the 13th member of the jury,” Harmon said.

Huffaker could not be reached for this story.

Metro’s part-time cold case detectives declined to be interviewed. A department spokesman said police have no new information and are not pursuing any leads.

The lawsuit

About a year after his acquittal, Haupt filed a $4 million lawsuit against Metro, Tom Dillard and another detective, Robert Leonard, alleging the detectives and the department conspired to violate his civil rights. The city of Las Vegas and Clark County also were listed as defendants.

Haupt claimed detectives misused photos taken from the Whiskey Pete’s arcade and that police filed false and misleading affidavits to secure a search warrant. He also claimed police tried to coerce a confession, according to news reports. He cited Dillard’s phone call to the judge as an example of being denied a fair trial.

J. Pat Horton, an Oregon-based attorney who litigated the case, said Dillard and Leonard picked Haupt as a suspect first, then tried to stack evidence against him.

“They did everything they could in terms of twisting evidence, ignoring evidence, misrepresenting evidence,” Horton said recently. “They were bound and determined to convict him.”

Horton said police essentially ignored a latent fingerprint on Alexander’s glasses.

“They should have done something with that fingerprint,” he said, adding it did not belong to Haupt.

News stories said the print shared some similarities with Haupt’s fingerprint, but they also had differences, so no substantial connection could be made.

Neither Dillard nor Leonard could be reached for this story.

After litigation, Haupt was awarded a single dollar in general damages and $1 million in punitive damages, Horton said. Court records show the case was fought for more than seven years.

A federal judge ruled the award excessive and threw out the punitive damages. Haupt later agreed not to pursue a judgment and to have attorneys fees reimbursed.

Haupt said if he had known how much trouble the lawsuit would be, he probably would not have filed it. He said he still believes in the justice system, but he thinks its flaws are in some of the people who run it.

Aftermath

The years after his acquittal brought trauma and turmoil for Haupt. The mere sight of a police car sent him into a tailspin.

“It was borderline panic attack,” he said.

The emotional trauma Haupt said he experienced still bubbles up occasionally.

“There’s emotional scarring from that process that’s only one or two levels below that of conscious memory,” he said.

Haupt said he has never spoken to the boy’s mother, Roxanne Harris, because he never had a reason to.

“It’s tragic what happened to their family, but I didn’t have anything to do with it.”

Roxanne Harris could not be reached for comment.

“I’m still in the same house that the FBI went through from top to bottom looking for all that dastardly evidence they were sure they were going to find,” Haupt said. “But they didn’t, because there wasn’t any.”

Contact Blake Apgar at bapgar@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5298. Follow @blakeapgar on Twitter.