Criticism of Las Vegas constable Bonaventura grows

John Bonaventura makes people nervous.

As the elected constable for Las Vegas Township, Bonaventura is a Nevada peace officer, as are the undisclosed number of deputies he employs.

Constables look like cops - uniform, badge, gun, handcuffs, car with emergency lights - and they have much the same arrest powers as cops, but they're not quite the same. Constables are paid to serve legal papers for law firms and for the courts, and to evict tenants for landlords. They don't fight crime.

Nevada has long had constables, so it's not the job or scope of Bonaventura's power that makes people nervous. Nor have there been many complaints about things like use of excessive force, corruption or illegal activities.

What makes people nervous is the way Bonaventura runs his office.

During Bonaventura's two years as constable, his office has seen controversies that include a roundly criticized foray into reality television, allegations of sexual harassment, jurisdictional disputes and the hiring of deputies with questionable histories.

Concern about Bonaventura's office has grown to the point that his peers openly call him unprofessional and a state lawmaker is drafting legislation that would curtail the power and independence of all 14 Nevada constables.

North Las Vegas Constable Herb Brown said Bonaventura has "ruined the image" of all constables.

"People assume that we are all the same, and that we're all from that same office, and that's unfortunate," Brown said.

Bonaventura counters that he's just doing his job.

"I'm proactive," he said. "I'm trying to enforce the law."

Nevada's elected constables are generally low-key public officials whose mundane-sounding duties - delivering paperwork - belies their most significant power: They can make almost anyone into an armed peace officer, as long as that person is not a felon or a sex offender.

And a constable's deputies are not county employees; they work only for the constable and are paid with service fees. So it's unclear if anything about them is a matter of public record.

Bonaventura rejected a Review-Journal request for a list of his deputies' names, saying he is concerned his 20 or so employees would sue him if that information were released. That's in stark contrast to police officers, whose names, salaries and affiliations are public record.

A TALE OF TWO DEPUTIES

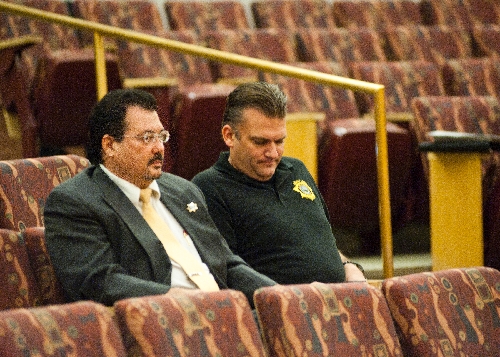

Bonaventura's top two deputies are widely known, however. Lou Toomin, the constable's spokesman, and Jason Watkins, his chief operating officer, both make public statements for Bonaventura and represent the office at public events.

Toomin, 77, served with Bonaventura in the Nevada Assembly in the 1990s. He was made a deputy in February, even though California court records then showed him to be a felon.

Toomin was 31 in 1967 when he was convicted of grand theft auto in Los Angeles. Toomin said he was going through a rough period then, and did not realize the felony conviction was on his record until it popped up during a background check when he tried to buy a weapon for use on the job.

"The real question is how did this go on for so many years, and it wasn't being picked up?" Toomin said. "It was a miscommunication somewhere. If I completed the probation, which I did, and if I paid the $300, it was (to be) reduced to a misdemeanor."

The conviction was indeed reduced to a misdemeanor, 45 years after the fact, after Toomin contacted California authorities.

Toomin now carries a gun at work, but only because he has the same concealed carry permit any law-abiding citizen can get in Nevada. Because of his age, he is unable to complete a required law enforcement training course to become certified as a peace officer, which is supposed to happen within a year of a deputy's hire. Bonaventura appears to have skirted that requirement by revoking Toomin's oath as a deputy before the deadline, then changing his job title.

EVICTION QUESTIONS

Watkins, 39, who runs Bonaventura's office finances and technology, has had more recent problems.

Court records show landlords have filed papers more than 20 times to evict him from commercial and residential properties since 1999.

In most of the situations, landlords used the constable's office - Watkins' employer since last year - to notify him that his rent was past due and he would be kicked out if he didn't pay. Watkins has been evicted at least twice.

Last year, a business Watkins helped create, the now-defunct Lucretech Inc., was evicted from its office on West Sahara Avenue.

According to the constable's website, tenants who are locked out of a property pending eviction must make arrangements with the landlord to retrieve their personal property. That's apparently not the rule when the tenant is also a deputy constable.

According to a security guard's report for Nov. 19, 2011, obtained by the Review-Journal, Watkins carried out items from the office after being evicted, and no landlord's permission was noted.

Bonaventura said he was aware of one eviction involving Watkins, around the time he began working for the constable's office. It's unclear if the business complex eviction was that incident.

Watkins "said he wanted to give me a heads-up in case I saw something," Bonaventura said. "I said, 'Well, look, that's not my problem. It's a personal matter. If you don't pay your rent, that has nothing to do with you working here. It has something to do with your landlord. We would process that eviction like we would any other eviction.' "

Also on Bonaventura's payroll are Deputy Ken Twiddy, who was recently fired from the Nevada Highway Patrol after he was accused of sexting a co-worker - he denied the allegation and is trying to get that job back, according to court records - and Deputy Luis Rendon, who in 2000 was arrested for burglary and grand theft in Miami, but was never charged.

Rendon's driving record shows a long list of traffic violations and four license suspensions for failure to pay fines. Bonaventura said he was not aware of their backgrounds, which someone else was responsible for researching.

Pennsylvania court records also show that Nathan W. Schlumpf, a constable process server and a former candidate for state Senate District 5, was arrested in 2005 on drug charges and pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.

Schlumpf denies he was ever arrested, though the name and date of birth he lists on his Facebook account match the Pennsylvania court records.

Another deputy, Jesse Cantero, was arrested Sept. 21 by Las Vegas police for driving with a suspended license and DUI - his second in three years.

Cantero was in the process of becoming a certified peace officer through the Las Vegas Law Enforcement Academy, which Bonaventura's office sponsors. Constable dollars paid for Cantero's attendance, as noted on a check signed by Bonaventura and obtained by the Review-Journal. But Cantero, a former candidate for Assembly District 16, apparently was fired for not showing up to work on Sept. 17, according to Lisa Mayo-DeRiso, who was representing the law enforcement academy.

It is unclear if Cantero finished the academy, because he was arrested the night of the academy graduation and did not attend the ceremony.

Bonaventura said he follows "strict regulations" when it comes to hiring deputies and process servers, but state law says only that a person convicted of a felony or a gross misdemeanor can't be a peace officer.

Bonaventura said, "You can't discriminate against someone because they've been arrested. ... If you're not convicted, you're innocent until proven guilty. You can be accused of anything."

Controversy is no stranger at the Las Vegas constable's office.

In 1993, Las Vegas Constable Don Charleboix was indicted for deputizing campaign contributors. When the Clark County Commission abolished the office and then re-created it two years later, Constable Bob Nolen was fined by the state Ethics Commission for working 25 hours a week but drawing full-time pay, though the ruling was later overturned.

In the intervening years, the constable's office received little attention until 2010. That's when Bonaventura, 50, a Democrat whose father was the elected constable in the 1980s, was voted into the $100,000-a-year post after serving two years in the Nevada Assembly, from 1993 to 1995.

Now Assemblywoman Marilyn Kirkpatrick, D-North Las Vegas, is proposing a bill that "revises provisions governing constables" to be introduced when the Legislature convenes in February.

Kirkpatrick said she wants to re-evaluate the role and responsibilities of constables statewide.

"I just think times have changed," she said.

And she wants to know more about who constables are accountable to and who they're hiring.

"I don't really know who or what kind of oversight there is," she said. "If you have a problem with their office, who do you go to?"

Kirkpatrick said she is researching how court business is done in places such as Washoe County, which doesn't have a constable. And she wants to set minimum qualifications for who can run for the office. Five years of police experience is required for candidates for Clark County sheriff, she notes.

Bonaventura in campaign materials has said he attended the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Ga., to become a certified peace officer in 1986. The Glynco center, now operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, provides training for 91 federal, state, local, tribal and international law enforcement agencies. Documentation of his time there is unavailable, however.

Bonaventura won't sign forms that would allow the Review-Journal to access his records.

Without giving details, the constable also has said he worked with the U.S. Department of Justice from 1986 to 1991 in San Pedro, Calif., and that he has been employed as a corrections officer and a security officer.

While he has not attended a Nevada police academy, his election automatically made him a certified peace officer.

Kirkpatrick said her interest in constables was sparked when she saw a pilot program for a failed TV reality show set in Bonaventura's office. The fact that deputy constables were filmed waving guns and using profanity during traffic stops prompted sharp criticism from county commissioners in January.

"You could not do a worse service to the taxpayers of Clark County," Commissioner Steve Sisolak said at the time. "I just can't believe you would be proud of this."

Bonaventura said he dropped the idea.

DRAWING ATTENTION

Bonaventura attributes much of the criticism of his office to competition.

There are 11 elected constables in Clark County, from constabularies that range in size from Las Vegas Township, which has multiple employees and a $3 million budget, to one-constable offices in Moapa and Searchlight.

In larger offices, the county pays for secretaries and other administrative support. In Las Vegas Township, the county sets the constable's pay at a flat $100,000. In other jurisdictions, the pay varies by volume of papers served.

All of the offices, regardless of size, collect fees for their services, so their volume of work determines the money they bring in.

Bonaventura has been aggressive in defending his turf against what he considers encroachment by other constables. In June he sued Mitchell and Laughlin Township Constable Jordan Ross, whom he accused of "border jumping.''

Bonaventura complained that he recently lost a $50,000-a-month account with a Las Vegas law firm to Henderson Constable Earl Mitchell.

In August, the Nevada Supreme Court removed a lower court judge's injunction that temporarily stopped constables from jumping borders. The courts are still sorting out the case.

Bonaventura's personal conduct also has been questioned.

Former Deputy Kristy Henderson, who was fired earlier this year, filed a discrimination complaint in July, citing allegations of sexual harassment by Bonaventura since he took office.

The allegations include Bonaventura telling Henderson that she has "a hard body," and that he walked around the office with the fly of his pants open "on purpose," according to the 14-page complaint.

Bonaventura has denied the allegations, though his style can be less formal than most peace officers project.

Recently, as he gave two Review-Journal reporters a tour of his office, Bonaventura stopped at the training room and pulled out his Taser stun gun. While explaining that the stun guns have cameras to record incidents when they are used, he pulled the weapon's trigger. The Taser crackled blue with electricity for a few minutes as he explained that if he loaded a cartridge, and then pulled the trigger, small darts would lodge in the wall.

Mostly, the cameras capture deputies' feet, he joked as he switched it off.

Mitchell, the Henderson constable, said Bonaventura's management and approach to his job have "destroyed" relationships among constables.

"It's not that we didn't have differences, but we settled them at our meetings," Mitchell said. "Things didn't go public. It ran smoothly.

"It's my opinion that (Bonaventura's) actions, unfortunately, painted us with a broad brush on whatever the Legislature has in mind."

Mitchell and Brown, the North Las Vegas constable, said they would like a new state law that would require constables and deputies to be certified peace officers before they are elected or hired.

"We have a valuable service to provide for the community, as long as you have the right people in place," Mitchell said. "I feel we're fighting for our survival."

Contact reporter Kristi Jourdan at kjourdan@review journal.com or 383-0440. Contact reporter Lawrence Mower at lmower@reviewjournal.com or 405-9781.