Critics: No way for federal employees to safely blow whistle

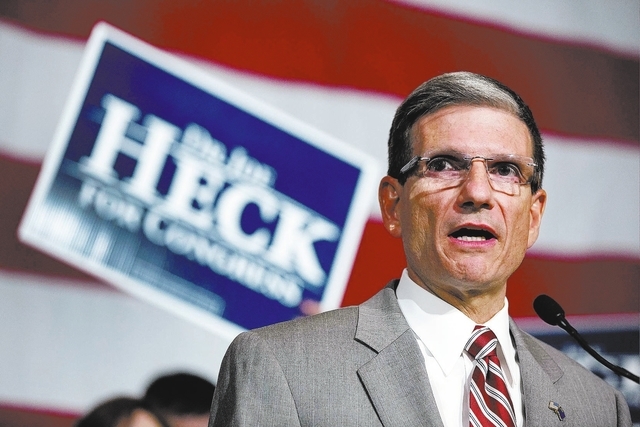

Nevada Rep. Joe Heck is clear when it comes to the subject of former intelligence contractor Edward Snowden.

Heck, a Republican and member of the House Permanent Committee on Intelligence, says if Snowden had a problem with spying by the National Security Agency, he should have reported it to superiors within the government chain of command.

“There is a chain of command — use it,” Heck said during a discussion in August at the Review-Journal.

But advocates of government whistle-blowers say Heck and other critics are glossing over a major fact in saying Snowden should have used authorized government channels to shine light on broad government suveillance of Americans instead of leaking sensitive information.

They say federal laws, including one added late last year to the Defense Authorization Act with backing from Heck’s committee chairman, make it difficult if not impossible for someone in Snowden’s situation to report wrongdoing within classified intelligence circles without fear of retaliation.

The defense bill initially extended retaliatory protection to intelligence agency contractors but was amended to exclude those workers, according to people who worked on the legislation.

“There are no protections under the law for Snowden or anyone like Snowden,” said Angela Canterbury, director of public policy for the Project on Government Oversight.

“There was never a vote on it; there was never a public debate on it,” Canterbury said of the change.

Capitol Hill aides and attorneys who work with whistle-blowers said the change was made at the request of Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Mich., chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, most likely because that panel had the strongest jurisdiction over the matter.

While the modification was just a few sentences buried within hundreds of pages of legislation, it had huge ramifications for people such as Snowden who handle classified material and who might be troubled by what they discover.

It meant they would not be shielded from being fired, demoted or intimidated for reporting what they believe to be wrongdoing, the whistle-blower advocates say.

“They might spend time in jail,” Canterbury said. “That is the kind of retaliation faced by people like Snowden even if they use legal channels.

“It is ludicrous to suggest Snowden could have safely blown the whistle using legal channels and had any protection,” she said.

Despite the exemption, President Barack Obama, Heck and others maintain that Snowden should have made his concerns known within the agency.

At a news conference in August, Obama referenced an executive order he signed “well before Mr. Snowden leaked this information that provided whistleblower protection to the intelligence community — for the first time. So there were other avenues available for somebody whose conscience was stirred and thought that they needed to question government actions.”

The president’s comment was criticized as misleading. The executive order, PPD-19, did not cover government contractors, according to Washington Post columnist Joe Davidson, who spoke with whistle-blower advocates.

Susan Phalen, an intelligence committee spokeswoman, said intelligence community workers already are covered by the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Act of 1998. Under that act, she said, workers can bring complaints to an inspector general and to the proper intelligence committees.

“This formulation is designed to protect both employees and classified information, which protects the national security interests of all Americans,” Phalen said.

But Tom Devine, legal director for the Government Accountability Project, said the 1998 act is “false advertising.”

The act, Devine said, makes it legal for people to make such complaints within channels, but “there is no protection” from retaliation for doing so, he said.

According to documents leaked by Snowden and reported last month by the Washington Post, concerns about such leaks are longstanding.

The U.S. intelligence community “long before Snowden” was worried about “anomalous behavior” by employees and contractors that have access to classified material and was planning to reinvestigate at least 4,000 people who hold high-level security clearances, the newspaper reported.

Heck spokesman Greg Lemon said the exemption for intelligence community contractors makes sense because whistle-blower protection is not a shield for people who leak classified information that could “put Americans and our national security at risk.”

The whistle-blower section of the defense bill aims to increase protection for people who expose violations of law, waste or abuse of authority related to contracts or grants, Lemon said.

“Heck supports protections for covered activities and maintains his belief that the unauthorized leak of classified information represents a criminal act because it puts Americans and our national security at risk,” Lemon said.

But Canterbury said exempting intelligence contractors from whistle-blower protection has broader ramifications.

“He could have said to Congress, ‘I think this is an abuse of authority and I need to be protected,’ but that wasn’t even an option for him because it was exempted,” she said.

Canterbury added that even if it were later determined no violation of law or abuse of authority had occurred within the NSA, Snowden still might have expected some protection from retaliation because whistle-blowers generally aren’t obligated to prove wrongdoing.

The matter of legal protection from retaliation is no small issue for potential whistleblowers.

In an interview in June with USA Today, three former NSA officials who said they tried to report abuses through internal channels detailed fallout that included being forced from their careers, seeing their reputations attacked and watching friendships evaporate.

In one instance an inspector general turned whistleblower Thomas Drake over to the Justice Department for prosecution, according to Drake’s attorney, Jesselyn Raddack, of the Government Accountability Project.

“Not only did they go through multiple and all the proper internal channels and they failed, but more than that, it was turned against them,” Raddack said.

Drake gave unclassified information to a Baltimore Sun reporter who was investigating the government’s decision to choose an inferior surveillance software program despite its higher cost. Drake’s home was raided by authorities, he was forced from his job and was charged with violating the Espionage Act, making him liable for decades in prison if convicted.

The serious charges were dropped. Drake pleaded guilty to “exceeding authorized use of a computer” and received one year of probation.

Devine said the irony of making it more difficult for contractors to expose problems actually forces them to go outside channels, often to the media.

“People like Mr. Snowden do not have a legally safe option,” Devine said. “The only option that doesn’t mean professional suicide is an anonymous leak to the media.”

Follow Benjamin Spillman on Twitter at @BenSpillman702 or email him at bspillman@reviewjournal.com