Las Vegas police reserve program touted

When people hear the term, “reserve police officer,” their first impression doesn’t always match reality.

Critics might picture a bumbling Barney Fife patrolling the streets of Mayberry, but Kevin McMahill sees an opportunity for a dedicated volunteer officer force with the same abilities as a full-time Las Vegas police officer.

“People have a natural reluctance to think we could field a fully capable reserve officer ... because they think those officers wouldn’t be up to par in training,” said McMahill, deputy chief of the Patrol Division.

“The reality is, they would have the same training and the same requirements as a regular officer. And it’s proven to be effective in so many other jurisdictions,” he said.

Phoenix, Los Angeles and San Diego are three nearby cities with a healthy reserve program, McMahill said. Las Vegas used reserve officers more than 20 years ago, although the practice was eventually dissolved.

“We’re one of the few last major police organizations that doesn’t have a robust reserve officer program,” he said.

McMahill has pitched his bosses on the benefits of such a program for a long time. Recently, they started listening.

The deadline for applicants to the first reserve academy was midnight Friday. As of Friday morning, the department had received almost 500 applications.

The academy could begin in September or October, barring any bumps in the road. The applicants who pass their background test, a 420-hour police academy and 200 hours of field training — likely a small percentage — could start patrolling Las Vegas as early as next year.

The reserve academy requires about half the hours of the regular department academy because some functions — such as driving — are not needed. Reserves also won’t be trained to take complicated narcotics or sexual assault reports.

But little would distinguish a reserve from a full-time officer. They would wear the same uniform, put on the same badge and carry a gun. The main difference is reserves will work part time and won’t be paid.

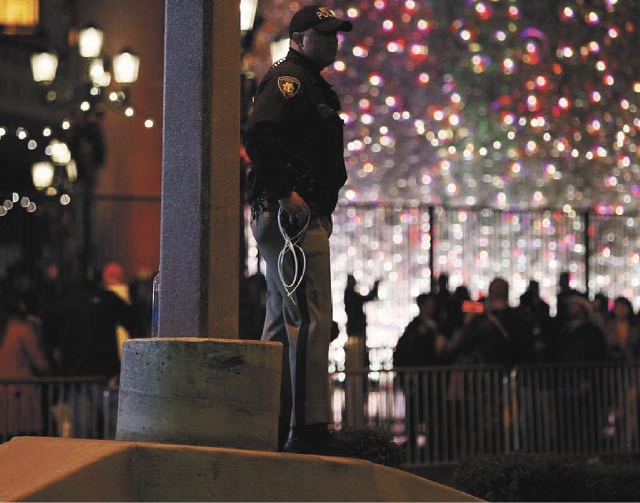

McMahill’s vision is for the first batch of reserves to supplement Operation Safe Strip, a longtime program to boost the number of officers on Las Vegas Boulevard at high-traffic times, especially on the weekend and during the summer.

Currently, the department moves a few officers assigned to each local area command and places them on the Strip each weekend. But pulling officers from their normal assignments drains resources in the neighborhoods.

Each reserve would be paired with a full-time officer, likely on a foot-patrol beat or in a two-person squad car. The main focus will be to increase the “visible presence” at the city’s economic hub.

“The reality of it is, we’re still not effectively policing up there. There are 300,000 visitors at any given time up there. It’s a difficult job,” McMahill said.

Deputy Chief Gary Schofield, who will oversee the human resources of the program, said the Strip is the lifeblood of the community and must be properly staffed.

“The reason my family is here and everybody else’s family is here, and the livelihood we have is because of Las Vegas Boulevard,” he said.

Schofield said police are looking for applicants with a strong sense of community.

‘PRETTY HEAVY-DUTY COMMITMENT’

Reserves will be required to work at least 20 hours a month, a large burden for people with full-time jobs and families, he said. And that’s after a long academy and field training period.

“Think about how many hours you have to go through to get to the level you need,” he said. “To do that two days a week, and one day on a weekend, is a pretty heavy-duty commitment. ... for an unpaid, volunteer position that requires you to spend an extraordinary amount of time getting trained.”

McMahill said he first proposed the idea of a modern reserve program when the department began feeling an economic crunch from falling property tax revenue.

“We were looking then at a $60 million budget deficit and there was no end in sight,” he said. “We haven’t hired anybody in awhile.”

The department is facing a projected $46 million budget shortfall in the next fiscal year, which begins in July.

As officers have retired and positions have been eliminated, McMahill’s officers are feeling the heat. The department is about 43 patrol officers from minimum staffing level.

At this pace, he expects to be near the “break even” point within a few months, he said.

“I have the largest organization in the department and the numbers continue to dwindle,” he said.

Not everyone is convinced reserve officers are the answer, however.

Allen Lichtenstein, general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada , said studies of the department — such as the U.S. Department of Justice study last year — showed problems with training and implementing policy.

“Putting people out there with half-training is just going to create more problems,” he said.

Lichtenstein said he hoped Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie would reconsider.

“While there’s obviously a budget shortfall, they might want to look at Metro officers already trained from areas that are not as important, such as administration things, and putting them on the street where they’re needed,” he said.

The department’s liability if a reserve officer makes a mistake is the same as it is with a regular officer. If a reserve officer is shot or hurt, he would be entitled to the same workers’ compensation.

Chris Collins, executive director of the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, the union that represents rank-and-file Las Vegas officers, said he hadn’t been briefed on the program and declined comment.

McMahill said the reserve program was never intended to circumvent the hiring of full-time officers.

A WAY TO CUT COSTS

The department will start hiring regular officers when its financial outlook improves. But a reserve officer is a way of reducing long-term costs, he said.

With 50 reserve officers, the department could save an estimated $500,000 in one year. With 275 officers, a proposed number after four or five years, the department could save an estimated $2.4 million.

Police have been finding ways to cut costs for several years, Schofield said.

Volunteer patrol services representatives already work in Las Vegas. The volunteers wear different colored uniforms and are not armed, but they can take basic reports, he said.

“A lot of what we do is just presence,” Schofield said.

If reserves want to transition to full-time officers, they would have to enroll in the department’s regular academy, which trains officers to operate as a regular one-person patrol officer.

They would likely have a leg up on their competition at the academy, with résumé experience as a Las Vegas officer. They would also have already passed the physical fitness, background, written and oral tests.

“Reserve programs allow you to sort of get a test run,” McMahill said.

If the program succeeds, McMahill said he hopes it would expand to other areas of the department.

A fleet of an additional 100 volunteer traffic officers could drastically cut down the number of fatal accidents, he said. Or a retired homicide detective could volunteer to investigate cold cases.

But that could be years away. At the very least, McMahill said he hopes the program will increase transparency with a community that has read about deadly police shootings and use of force issues for years.

Although the department fell short of its initial goal of 800 applications, McMahill said he thinks there’s substantial interest in policing the world-famous Strip, he said.

“It’s a cool part of our job,” he said.

Contact reporter Mike Blasky at

mblasky@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0283.