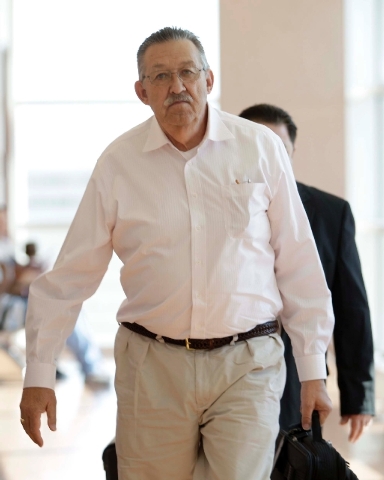

Prosecutors paint Dipak Desai as greedy, arrogant in closings; jurors begin deliberations Friday

Following seven hours of closing arguments, the jury late Thursday received the hepatitis C outbreak case against Dr. Dipak Desai and nurse anesthetist Ronald Lakeman.

The 12-member panel was sworn in after arguments ended about 7 p.m.

District Judge Valerie Adair instructed the jury to go home for the evening and start its deliberations Friday morning.

Earlier, a prosecutor told the jury that greed caused Desai to gamble with the lives of patients who were infected with the deadly hepatitis C virus.

“This case is about pennies,” Chief Deputy District Attorney Pam Weckerly said in her closing argument. “He was focused on saving money at every turn.”

Weckerly repeated what prosecutors said in their opening statement — that Desai conducted procedures at his clinics like an assembly line, stressing “volume over patient care.”

She described his methods as “reckless behavior.”

Her 70-minute argument was made before a packed courtroom in the 10th week of the trial stemming from the 2007 hepatitis outbreak.

Desai, who surrendered his medical license after health officials disclosed the outbreak in 2008, sat motionless, looking straight ahead, as the attorneys made their last pitches to the jury.

His lead defense lawyer, Richard Wright, in a nearly three-hour closing argument, acknowledged that Desai was a frugal businessman, but said that didn’t mean he hatched a scheme to deliberately infect his patients with the blood-borne virus.

“I’m not going to argue that he wasn’t a cheapskate,” Wright said. “He’s not on trial for that.”

Wright argued that none of the prosecution witnesses could definitively say how the hepatitis C virus was transmitted.

He told jury that prosecutors pushed the cheapskate theory to inflame and distract it from a weak case that couldn’t prove the defendants knew they were risking the health of their patients.

Wright accused prosecutors of putting pressure on witnesses, through grants of immunity, to fabricate testimony during the protracted trial.

“You pressure people hard enough, and they’ll come up with a story,” he said.

Lakeman’s lawyer, Rick Santacroce, urged the jury to “have courage” in its deliberations and “ignore the public outcry” in the high-profile case.

The public, he said, is “clamoring” for someone to punish for the hepatitis infections, and his client has become a “sacrificial lamb.”

“We call upon you to be strong,” Santacroce said. Then he looked at his client at the defense table and added, “The state, the public has vilified this man.”

Santacroce said prosecutors “failed miserably” to prove his client’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Prosecutors presented 70 witnesses in nearly eight weeks of testimony before resting their case Tuesday.

Desai, 63, and Lakeman, 66, did not take the witness stand in their own defense. They are facing more than two-dozen criminal charges, including second-degree murder, criminal neglect of patients, theft and insurance fraud.

The charges focus on the cases of seven patients infected with hepatitis C that health officials linked to Desai’s Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada on Shadow Lane.

One of the patients, 77-year-old Rodolfo Meana, died last year in his native Philippines.

Prosecutors argued that the virus caused Meana’s death. But defense lawyers presented a medical expert who testified Meana had other underlying medical issues, including bad kidneys, that could have cost him his life.

Throughout the sometimes emotional trial, prosecutors contended that unsafe injection practices involving the sedative propofol led to the outbreak. The combination of double-dipping syringes into propofol bottles used on multiple patients spread the virus from patients infected with hepatitis C on two different dates in 2007, prosecutors concluded.

But defense lawyers argued that the theory is not rock solid and that other means of transmission, including dirty scopes, biopsy equipment and saline vials, were possible.

Weckerly told the jury that people in their 50s, 60s and 70s aren’t supposed to go in for routine colonoscopies and come out with communicable diseases.

She said Desai created an environment at the now-closed endoscopy center that allowed the hepatitis infections to occur.

“Their infections were the result of laziness, sloppiness and arrogance,” she told the jury. “None of this needed to happen.”

Desai’s influence over his employees was so strong it forced them to go along with the risks, Chief Deputy District Attorney Mike Staudaher said, as he wrapped up the case for prosecutors with a 90-minute PowerPoint presentation.

“They checked everything at the door -- all their morals, ethics -- everything,” he said.

Desai’s operation relied on “speed, speed, speed,” as he churned out an average of 60 procedures a day at the Shadow Lane clinic, Staudaher said

In the end, Weckerly told the jury, “It wasn’t worth it, and they knew better. And they should be held accountable.”

Contact Jeff German at jgerman@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-8135. Follow @JGermanRJ on Twitter.