Wrongly convicted man shares story during Mob Museum discussion

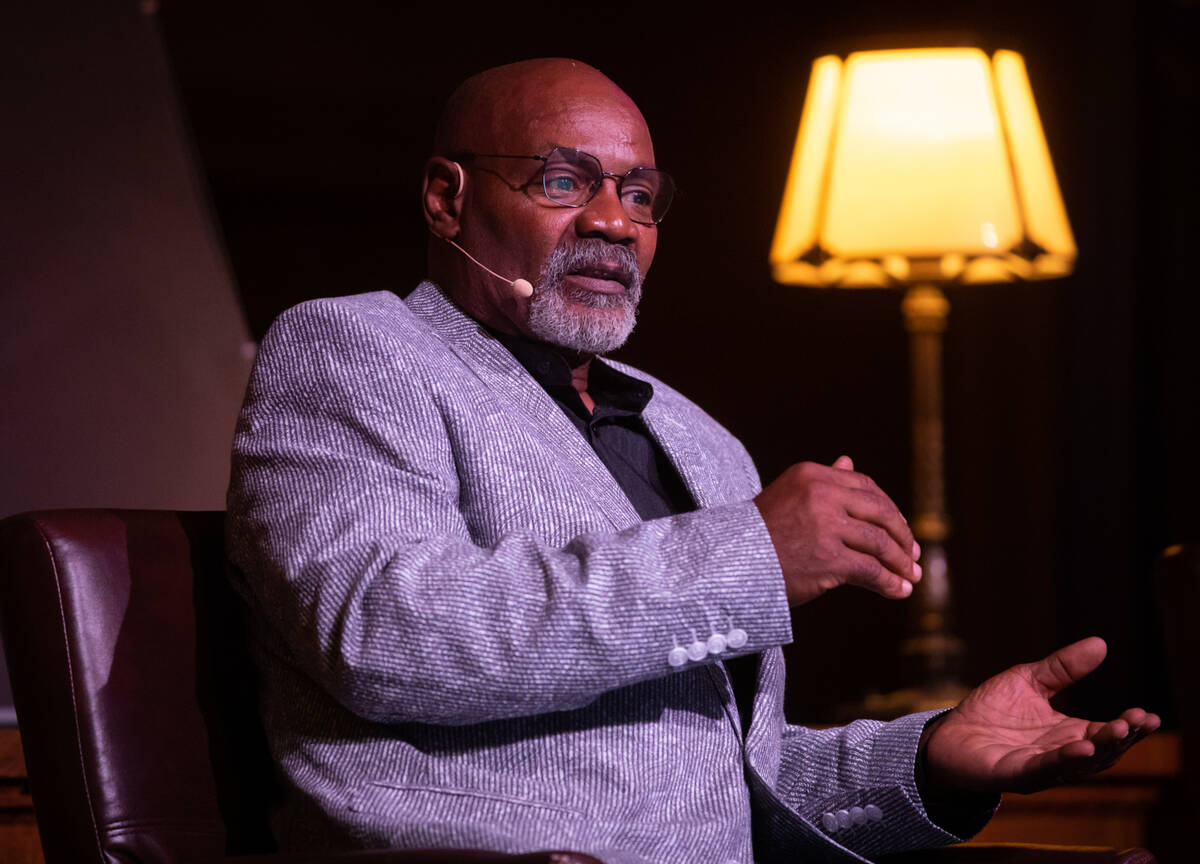

Marvin Anderson was driving an 18-wheel semi-truck in rush-hour traffic when he received the call he had waited years to hear.

He pulled over, got out of the truck and started dancing for joy on the side of the road when he was told that DNA evidence had been found that proved he had been wrongfully incarcerated for 15 years.

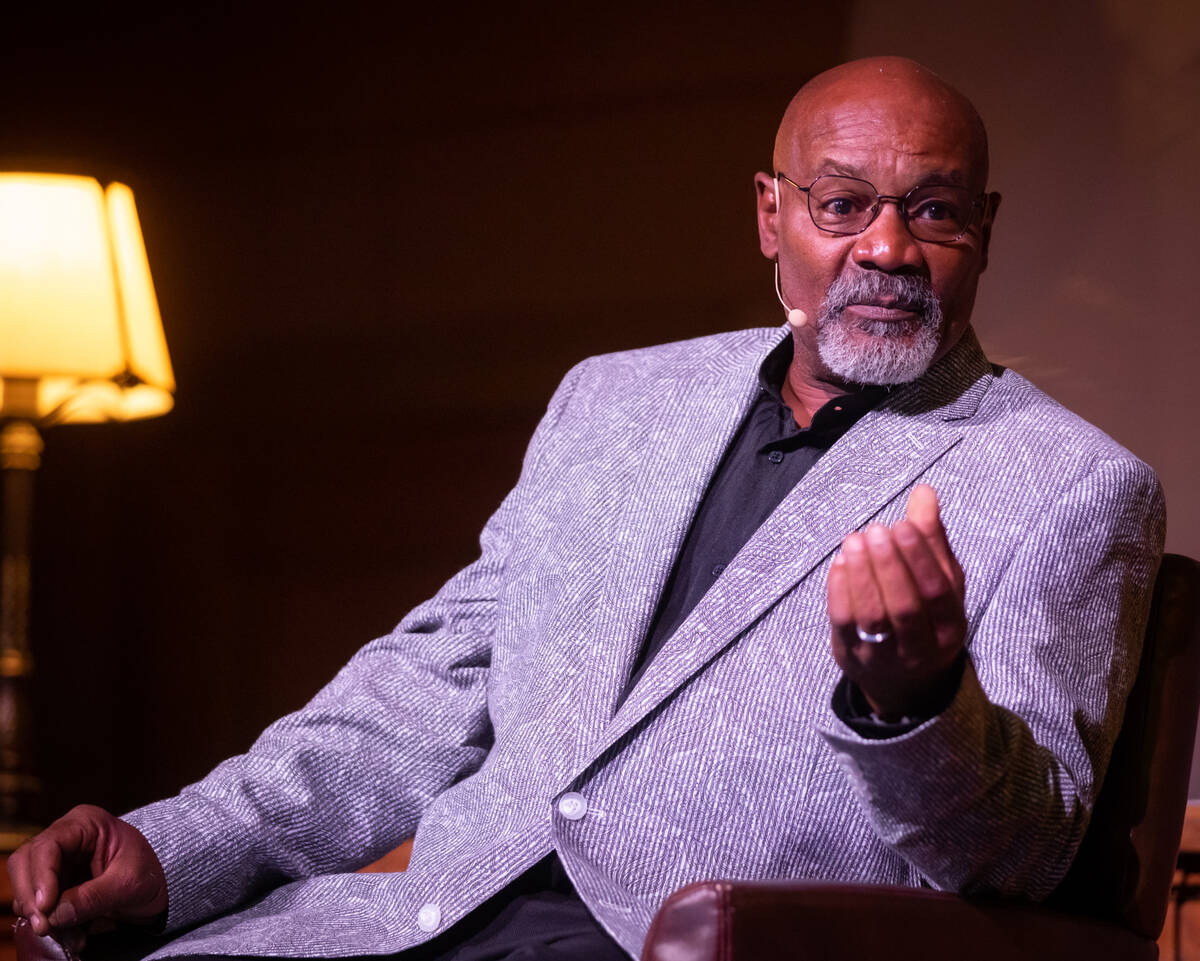

Anderson, now 58, shared his story Thursday night during a Mob Museum event titled “Righting Wrongful Convictions: DNA and the Innocence Project.”

“A lot of people in our society today, they still don’t believe that innocent people go to prison,” Anderson said.

In 1982 when he was 18, Anderson was convicted of rape, abduction and robbery by an all-white Virginia jury. He was sentenced to 210 years in prison.

“People also have to realize that what happened to me can happen to anyone on any given day,” Anderson said.

A white woman raped by a Black man misidentified Anderson as her assailant. Anderson had no prior criminal history so police used a color photo of Anderson from his work ID badge and included it with five other black-and-white photos that were shown to the victim.

An hour after reviewing the photo spread, the victim identified Anderson in an in-person lineup. He was the only person in the lineup whose picture was included in the photo spread.

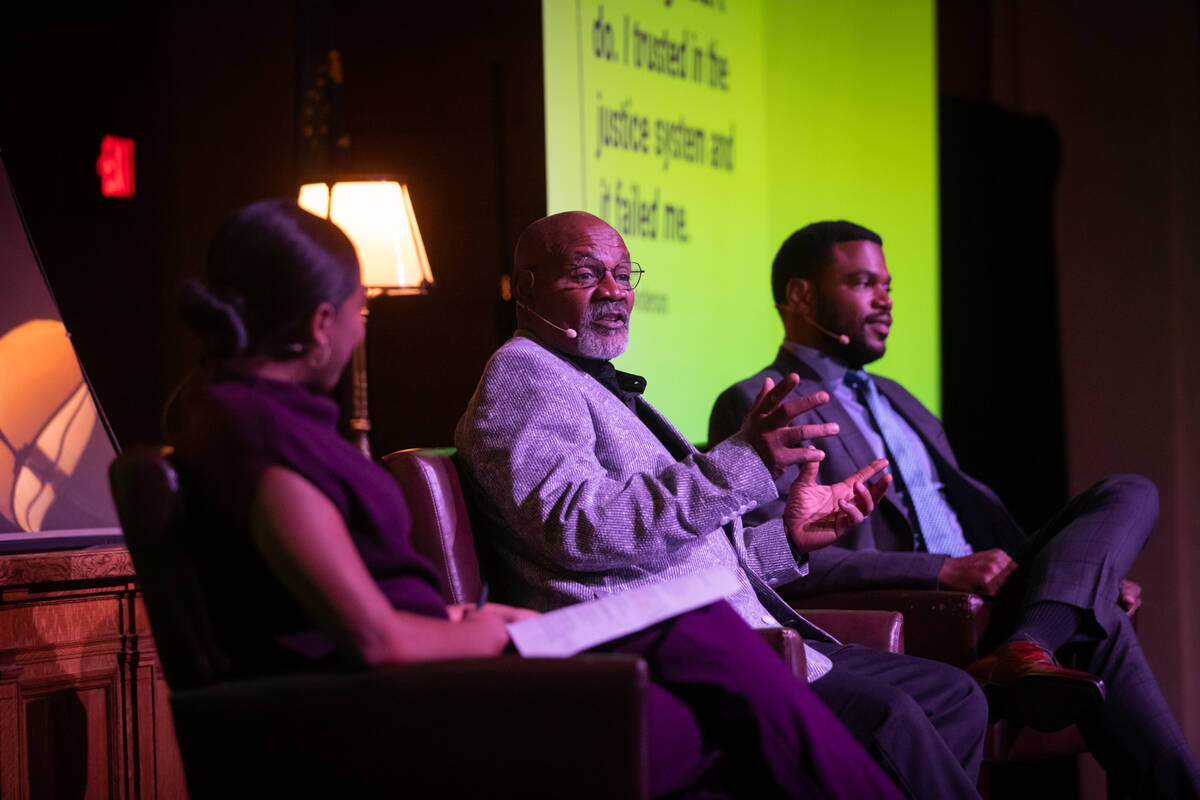

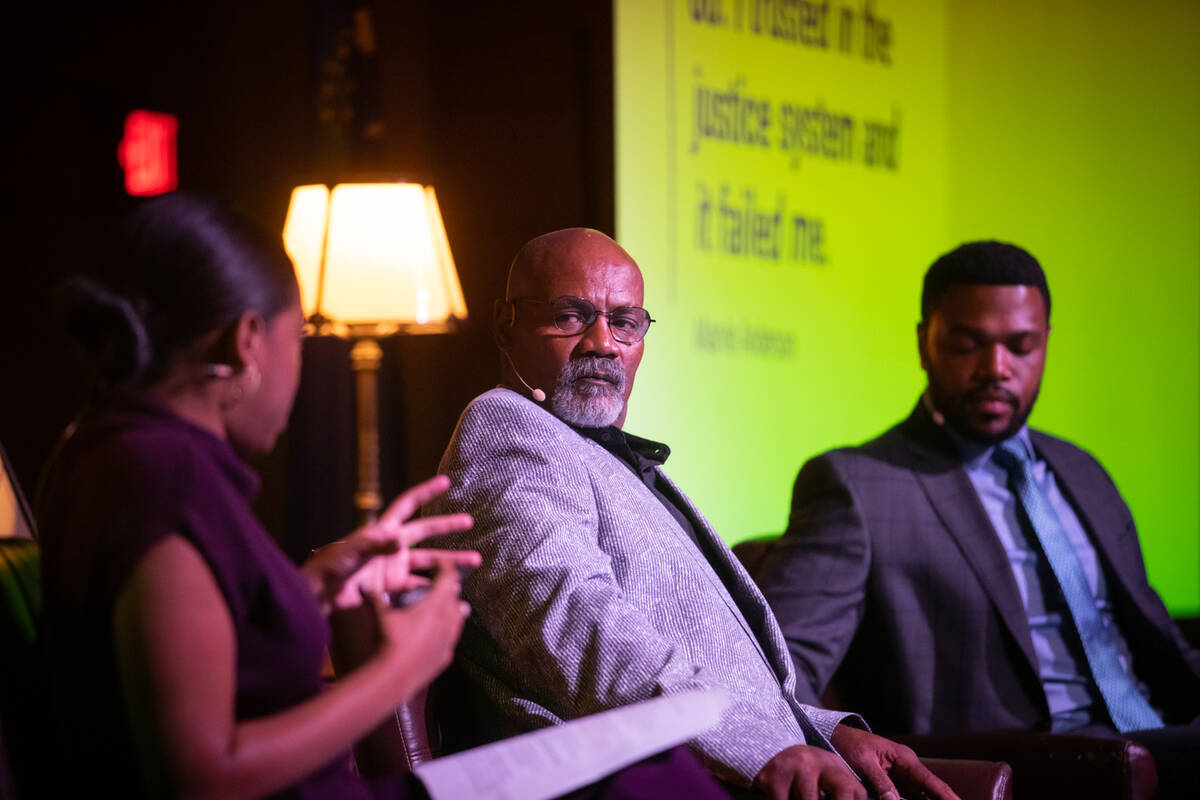

Museum Director of Public Programs Shakala Alvaranga moderated a discussion with Anderson, who was joined on stage by Anton Robinson, a senior staff attorney in the Innocence Project’s strategic litigation department and a former public defender.

“There is nothing more sobering than to stand next to someone who you genuinely believe, based upon everything that you know about their case, that they are not guilty and to see a jury return a guilty verdict,” Robinson said.

During the trial, Anderson’s attorney refused to call the man who would later admit to committing the crimes to the stand.

Anderson served 15 years in prison and then spent four years on parole.

“It’s important for us to be here today to ensure that everyone understands the causes of wrongful conviction and that we all do our part to do away with them if we can,” Robinson said.

Robinson said the Innocence Project, founded in 1992, works to free innocent people and make sure people are not wrongfully convicted in the first place.

“We work to create fair and equitable systems of justice for all of us. From people like Mr. Anderson and everyone,” Robinson said. “We should have a fair shake. If we’re going to call it justice, we should all have a fair shake.”

The Innocence Project took on Anderson’s case in 1994, and he was pardoned by Virginia Gov. Mark Warner in August 2002.

The DNA evidence that led to his exoneration was found in the notes of a Virginia criminalist who kept DNA samples from Anderson’s case. Tests of the samples excluded Anderson from being the perpetrator.

Robinson said approximately 15 percent of exonerations are because of DNA evidence. He said the leading factor leading to wrongful conviction is eyewitness misidentification, which is the cause in about 70 percent of wrongful convictions.

The Innocence Project looked at the first 375 people exonerated because of DNA evidence and found that those exonerated had served on average 14 years in prison. Of the first 375 people exonerated, 225 were Black, according to Robinson.

“We have to acknowledge that racial bias has an impact on the criminal legal system and the outcomes on the criminal legal system and we have to figure out very specific ways to deal with those,” Robinson said.

Access to DNA evidence and police files for review is a big step in being able to figure what led to a person’s wrongful conviction, he said.

Other common causes of wrongful convictions include police tactics that lead to false confessions and using forensics in a “non-scientifically defensible way” to mislead jurors.

Before his wrongful incarceration Anderson had been working to become a firefighter. After his release and exoneration, he became a firefighter and worked his way up to chief of the Hanover, Virginia Fire Department. He retired two years ago after serving as chief for 15 years.

Anderson serves on the board of directors for the Innocence Project.

“We have to keep fighting for this change,” Anderson said, “and that’s what I’m going to continue to do.”

Robinson said it is estimated that about 3 to 5 percent of people in prison were wrongfully incarcerated.

“If we think about the many millions of people that we have in prison today or convicted today, that still leads us to thousands and thousands of people who should not be in prison,” Robinson said.

Contact David Wilson at dwilson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @davidwilson_RJ on Twitter.