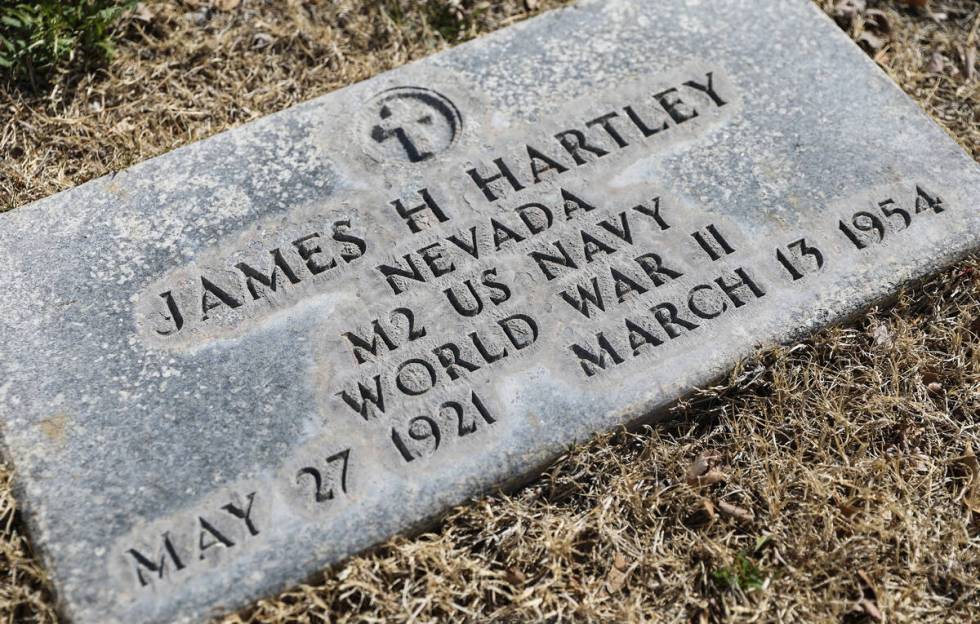

The body of 32-year-old James Hartley was found in a grave so shallow that his hand protruded through the desert soil, waving at traffic near what is now Harry Reid International Airport.

The Sheet Metal Workers union boss had been shot above his left eye in early 1954, and the circumstances around his death remain a mystery, even though at least eight people testified before a grand jury, some of whom authorities considered suspects.

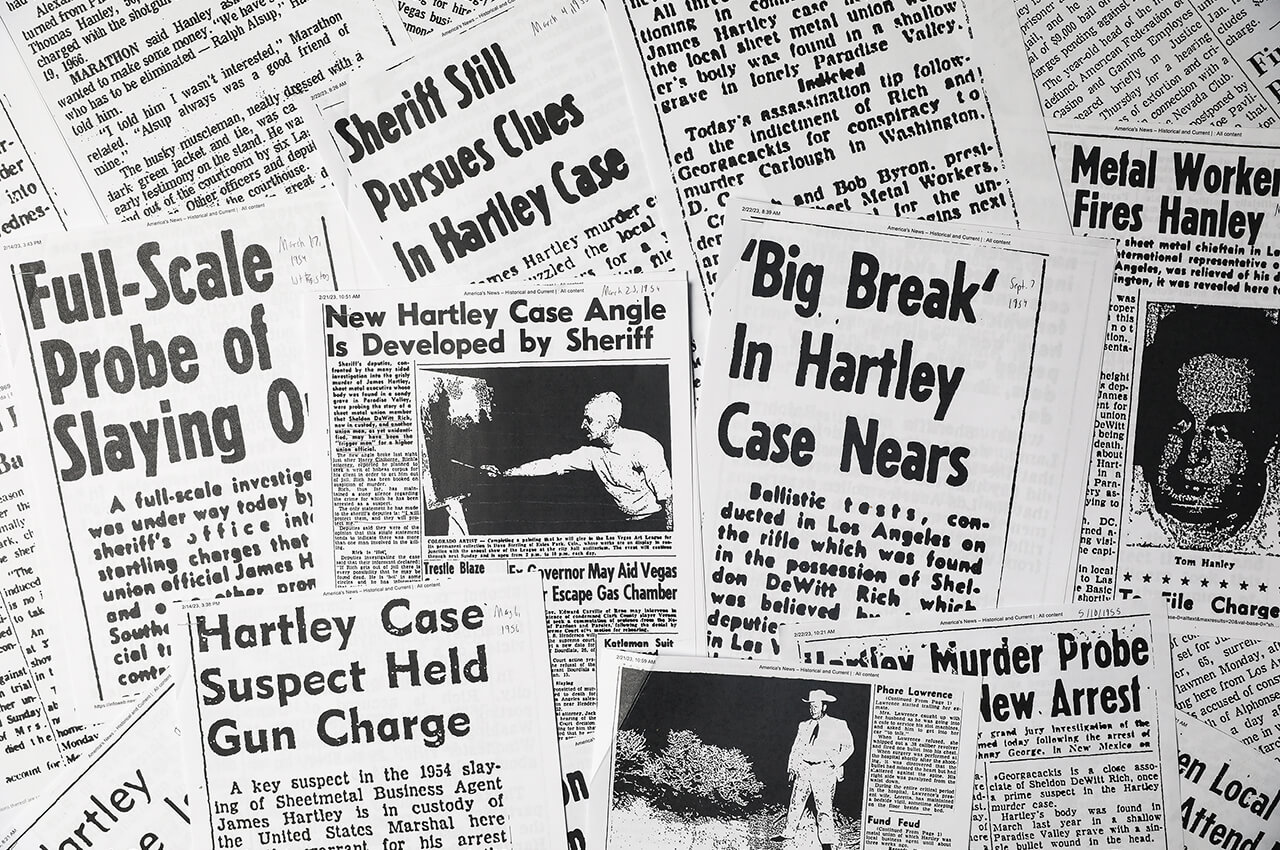

For a decade after the killing, as potential witnesses continued to come forward, rumors swirled about missing union money and shakedowns.

But nearly 69 years to the day Hartley’s body was found on March 13 of that year, no charges have been filed in his death.

The Metropolitan Police Department counts more than 1,200 killings as unsolved, with Hartley’s being the oldest. Police officials, however, refused interview requests for this story.

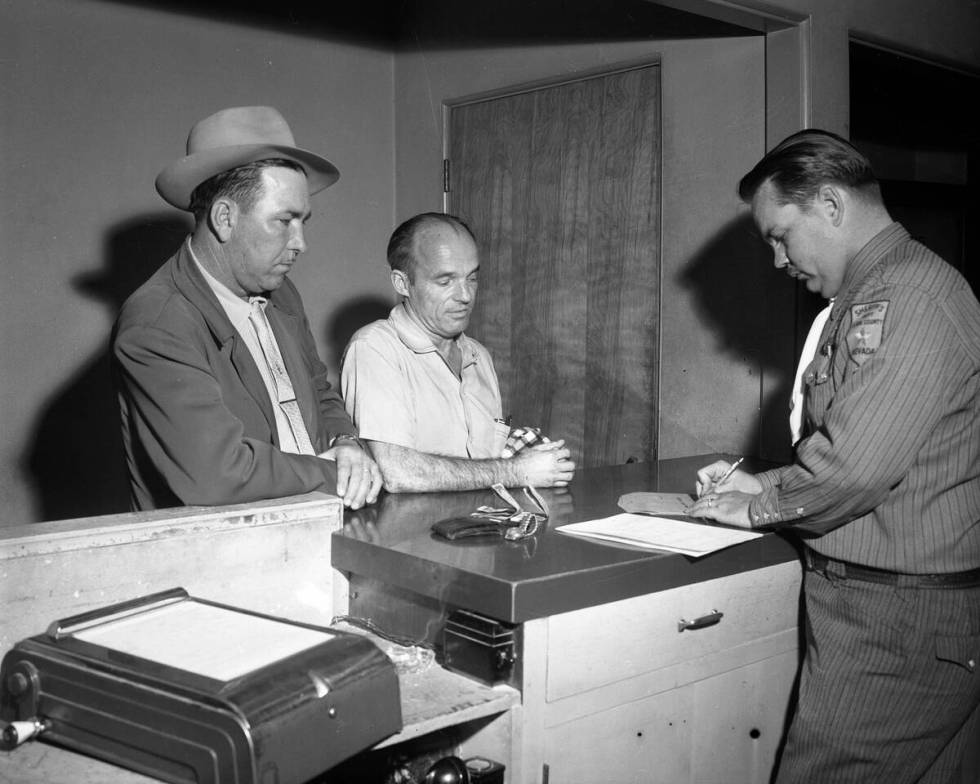

A convicted felon and reputed hitman, Sheldon DeWitt Rich, was the first person arrested in connection with Hartley’s killing.

FBI agents and Clark County deputies questioned Rich, who asked investigators what evidence they had on him and told authorities: “I will protect them, and they will protect me,” according to news archives from March 1954.

Rich was never charged in Hartley’s death.

“Even though the guys we’re talking about are not mobsters, it seems that they follow the criminal code,” Geoff Schumacher, with the Mob Museum, said of suspects in the Hartley investigation. “They’re not going to snitch on each other. Although the suspicion is that the reason Hartley was killed is that they were afraid he was going to talk and reveal everything going on.”

Authorities said the killer had used a .22-caliber rifle, and Hartley’s gold-rimmed eyeglasses were found near his makeshift grave along Paradise Road, though it was not clear whether he had been shot where his body was found.

Three days after the discovery, his wife, then 25-year-old Ruth Hartley, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that she had not seen her husband in almost a month. He had kissed her goodbye and said he was headed to Los Angeles. She assumed he had left her, she told the paper, as her husband had been “despondent for many weeks.”

James Hartley left behind a 10-month-old son, Thomas, and Ruth Hartley was three months pregnant with a baby boy when her husband was found dead.

The same day Ruth Hartley spoke with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, neighbors told the newspaper that two men had tried to “crash their way” into the Hartley apartment at 1154 S. Fourth St. a few days before he disappeared.

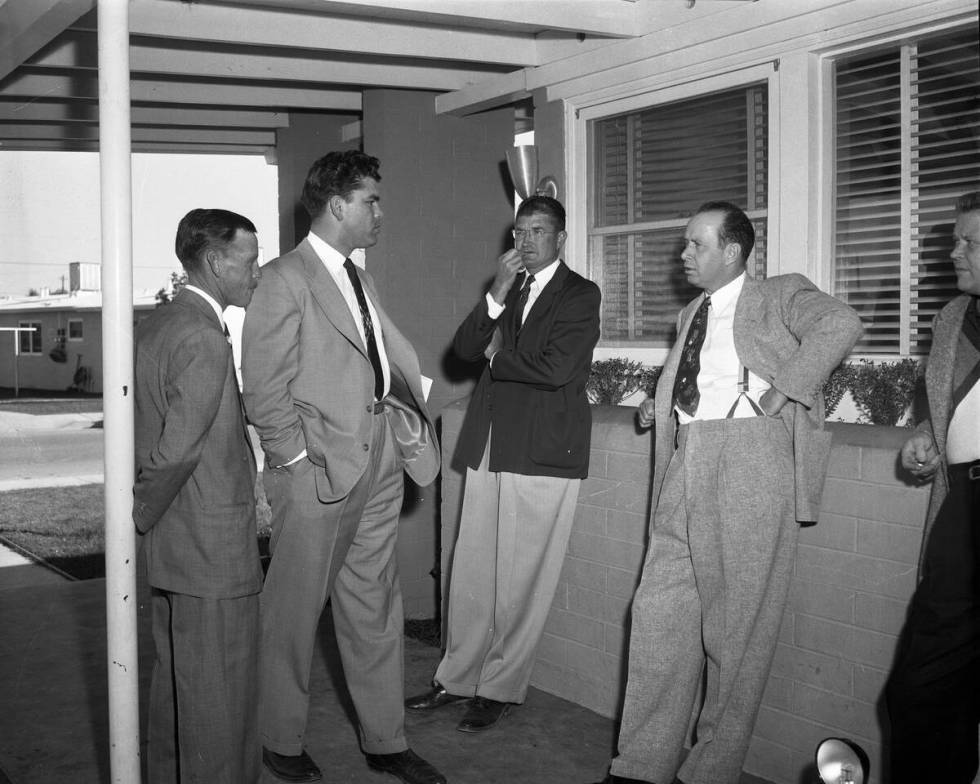

Then-Clark County Sheriff Glen Jones told the Review-Journal on March 16, 1954, that the killing might have been the result of a robbery, because Hartley’s 1953 Chrysler New Yorker sedan was missing, and he had not deposited thousands of dollars in union funds since July.

Jones said $1,700 in cash was found in Hartley home after his death, but anonymous reports to the police department at the time alleged Hartley may have lost thousands more and was trying to shake down a Los Angeles contracting firm by threatening “labor troubles” if they did not pay him, according to an article from March 16, 1954.

The shakedown was among the rumors police divulged at the time. Jones said Hartley could have been killed for losing the union’s money or for trying to double cross the union by secretly collecting his own revenue.

Days after Hartley’s body was discovered, his car was found outside a union office in Los Angeles with several bullet holes in the windshield.

Police said at the time that it was clear he was sitting in the car when he was killed, based on bullet trajectory above his left eye.

Less than two weeks after the slaying, detectives had identified a possible triggerman who had driven a car similar to Hartley’s, while they investigated rumors that there were orders to “quiet Hartley down” without killing him, according to a Review-Journal story at the time.

Sheet Metal Workers’ International Association representative Thomas Hanley told police and reporters that he would do everything he could to help solve Hartley’s killing, but by the end of March 1954, the Review-Journal reported Hanley had been ousted from the union because of suspected extortion.

Throughout the summer, police said a “big break” was imminent in Hartley’s death, and the case was presented to a Clark County grand jury with six possible defendants.

The big break?

Over the next several years, different people would come forward as possible witnesses.

After Hartley was found dead, one of his former friends, 39-year-old John E. Fuller, a sheet metal worker in Lynwood, California, told his wife that if he ever disappeared for more than 24 hours, she was to deliver a note he kept in the couple’s safety deposit box to the Los Angeles Police Department.

Fuller went into hiding in October 1954, and his wife, Virginia Fuller, followed through on her husband’s request.

The note detailed how he had given his .22-caliber rifle to Thomas Hanley, the ousted union member, “at the behest of the other sheetmetal union officials in Los Angeles,” according to a story from October 1954.

Virginia Fuller told the Review-Journal after her husband disappeared that he had been in constant fear of his life since Hartley was killed.

She cited threatening notes they had received, including one that read, “The next one will be buried hands down.”

Fuller had been expelled from the union in June 1954, along with Troy Nance and Carl Nichols. Police identified Nance and Nichols as suspects in Hartley’s killing and said Fuller’s letter “broke the case wide open.”

After Fuller returned home on Oct. 31, he and nearly a dozen other people were called to testify before a grand jury in Las Vegas, though it was unclear whether Fuller offered testimony.

David Cooper Nelson, a North Las Vegas sheet metal worker and convicted felon suspected in multiple slayings, was arrested in 1956 while driving a dead Nevada man’s car in Las Vegas.

Nelson told authorities he had amnesia and did not remember killing anyone. Investigators tried to “break Nelson’s amnesia,” hoping he would admit to killing Hartley and others, the Review-Journal reported at the time. Nelson was never charged in Hartley’s death, but he was sentenced to die for another killing in New Mexico.

In late 1964, John Wesley Barger, convicted of burglarly in Las Vegas, told prosecutors he had information about Hartley’s killing, and asked to cut a deal with authorities that would keep him out of prison. Barger said that when he was 14 he saw Hartley’s body being carried to a North Las Vegas home by the same person who had killed a friend of his, according to Review-Journal archives.

He said he could identify the killer in both cases. But no deal was struck.

Six months of grand jury

Prosecutors never indicted anyone in Hartley’s killing, and transcripts of six months of testimony before the grand jury were sealed while potential suspects walked free.

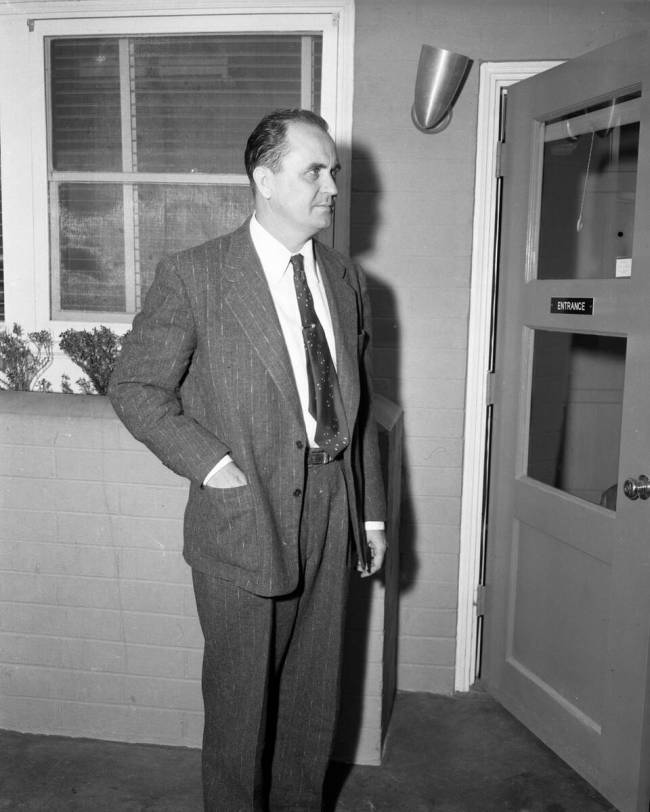

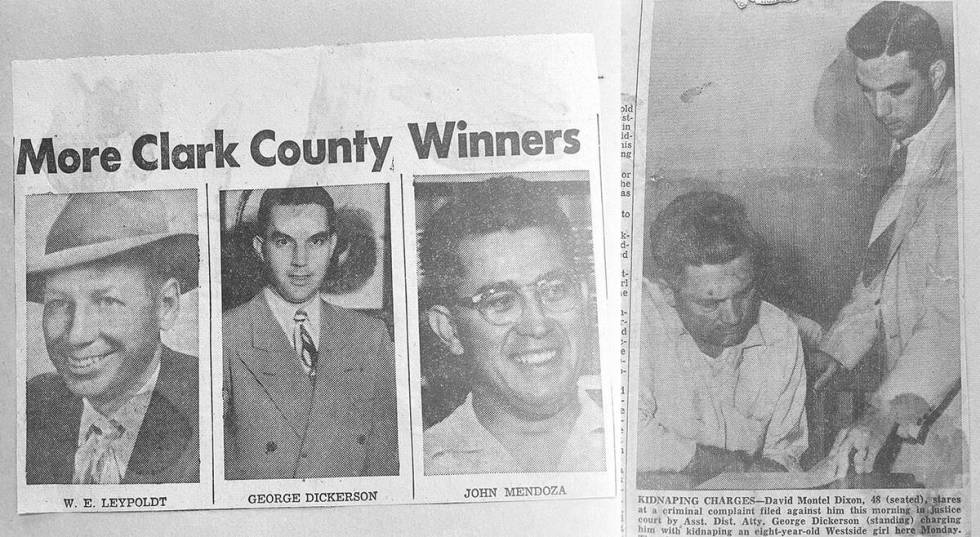

The late George Dickerson, Clark County’s top prosecutor at the time, oversaw grand jury proceedings in Hartley’s killing between November 1954 and May 1955.

Dickerson’s grandson Michael Dickerson now works as a chief deputy district attorney in Las Vegas.

“Talking to him about his time working as a DA, as a deputy and as the DA, it’s kind of uncanny how many similarities of things exist,” Dickerson said. “You had violence, you had organized crime.”

Dickerson’s grandfather never told his family about the Hartley case, but the younger prosecutor recalled that his grandfather’s life was often in danger while he attempted to charge people involved in organized crime in Las Vegas.

“I remember that he worked on some pretty intense cases including one that, as he’s working on a case, he got a call one evening that said, ‘You better do this or else your family is going to be dead’,” Dickerson said about his grandfather’s time as the district attorney. “If somebody is going to be so brazen to give the DA that call, what are they doing to the witnesses in those cases?”

Nichols testified before a Clark County grand jury, though the details of what he said were never made public. Nance, a former boss with the Laundry Workers Industrial union with a reported history of assaulting labor workers, had provided an alibi in the Hartley slaying, authorities said.

Schumacher said Hartley may have been planning to expose the union’s extortion, and a handprint of Rich, the suspected hitman, had been found on Hartley’s car.

A few months before Hartley was killed, Rich also had purchased a 1951 Chrysler New Yorker, which was nearly identical to Hartley’s green 1953 Chrysler. Police alleged that Rich had transfered his license plates onto Hartley’s car, which he drove through a checkpoint in Yermo, California and parked in Los Angeles, where the bullet-riddled sedan was later discovered.

Rich and John Georgacackis, a professional gambler from Las Vegas, were arrested in Washington, D.C. in August 1954 with a .22-caliber rifle and bullets police said matched the weapon used to kill Hartley.

In October 1954, Rich was extradited to Las Vegas, where he testified before a grand jury in Hartley’s death but was not indicted. Goergacackis was brought in for questioning on Hartley’s killing and later released.

Witnesses, suspects disappear

Hanley came to Las Vegas from Iowa in 1940 to work for the Basic Magnesium Plant in Henderson, while he lived in a small home on the corner of East Ogden Avenue and North 17th Street in Las Vegas.

“He had a reputation of being kind of a sociopath,” Schumacher said. “He was someone who was willing to bomb a restaurant or seriously hurt somebody or kill somebody without any regrets or hesitation.”

One of Rich’s associates, former union official Ralph Alsup, had been convicted of assault on another union officer. He was considered a suspect in Hartley’s death. While Alsup denied any connection to the slaying, he promised to help authorities.

Alsup was shot to death in January 1966 outside his home near Eastern Avenue and Sunset Road.

A 12-gauge shotgun used to kill him was found in sagebrush three miles from his home, which was open desert at the time he was killed.

Thomas Hanley was suspected in Alsup’s killing, but he was acquitted after one witness was killed in a fire at the home of Hanley’s sister and another was nearly beaten to death.

Schumacher said Hanley’s career in Las Vegas paralleled the rise of the mob in town, which was steadily investing in casinos that union workers built, but Hanley likely would have hated having a boss telling him what to do.

“Some people in hindsight, have speculated that he could have been involved in many more murders than they were ever investigating,” Schumacher said. “He’s definitely someone who was kind of mob-adjacent, if you will. He hobknobbed with people who were involved in the underworld.”

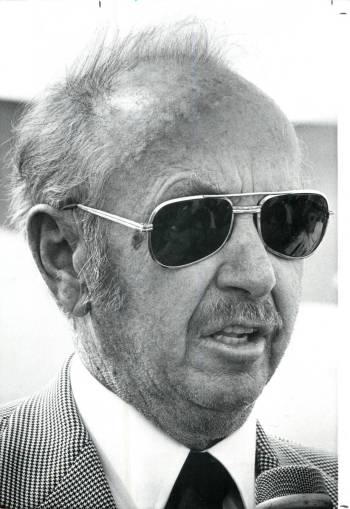

In 1977, Hanley and his son, recently paroled burglar Andrew Gramby Hanley, took their private jet from Phoenix to Las Vegas to face charges in connection with the kidnapping and slaying of Al Bramlet, a culinary leader who went missing and was found buried with his hands sticking out of the shallow grave on Mount Potosi.

In a press conference on the tarmac at the Las Vegas airport, Hanley said he was being harassed by the series of murder and attempted murder charges levied against him over the last two decades. Hanley died two years later, while serving prison time for Bramlet’s killing.

As for Hartley’s killing, Schumacher isn’t putting his hopes in solving this case, though he believes Hanley, Rich and several others conspired.

“There’s almost zero chance that some new piece of information is going to come out that allows them to close the books,” he said. “Everybody’s dead pretty much.”

Contact Sabrina Schnur at sschnur@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0278. Follow @sabrina_schnur on Twitter.