Remembering Neil Peart, Rush’s unrealized Las Vegas residency

A few months ago, I was deep in a conversation with a couple of entertainment reps who book residencies in Las Vegas.

It was all business until I asked, “What about Rush? I am still waiting for a Rush residency.”

And Bobby Reynolds’ face lit up.

“Rush was my first concert,” said Reynolds, AEG Live’s senior vice president in Las Vegas. “I put every kind of damn offer you can put in front of Rush.”

At that point, Reynolds’ longtime AEG colleague John Nelson chuckled as we delved into the insular Rush zone that fans know so well.

“That would be my dream residency,” I told Reynolds. “I would be there every night.”

“Las Vegas would have been the only place you could see Rush, and I think it would have been incredible,” Reynolds said. “I know their popularity, and their fans are all over North America and Canada. You look at that opportunity now — we’ll never know what it would have meant.”

This overture was made in late 2015 through early 2016. Reynolds envisioned Rush, with its 24 gold records and 14 platinum records (No. 5, all-time) playing T-Mobile Arena maybe four or six weekends a year. The idea was to stage the same type of recurring residency as the one headed up by country superstar George Strait, who has also quit touring.

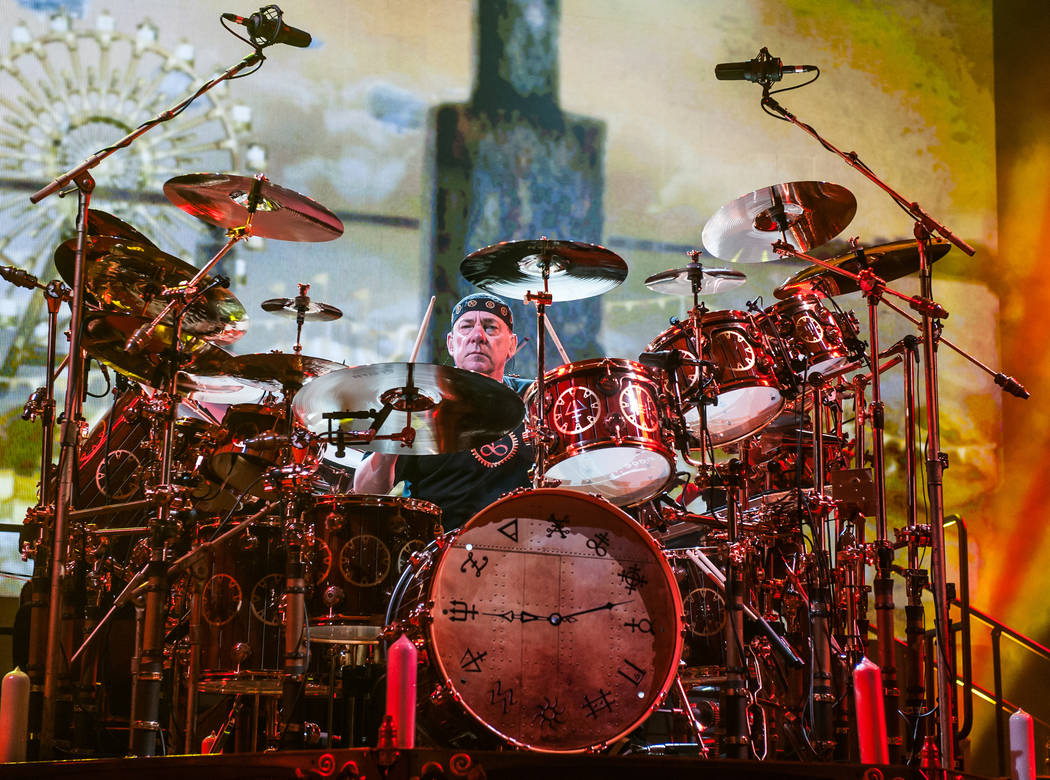

I recalled that conversation, that lost attempt, after learning Friday that Neil Peart, the peerless rock drummer and band’s lyricist, had died this week at age 67. Peart suffered from brain cancer over the past three years — certainly the unspoken reason there would be no Rush dates, in Las Vegas or anywhere else, after the band’s 2015 “R40 Live” 40th-anniversary tour.

The band’s last Vegas performance was at MGM Grand Garden Arena in July of that year; they would play just three more shows, even as fans in town mused about a possible residency on the Strip.

The news Peart had died hit legions of Rush fans with a shock, the type of information that leaves you dizzy, even confused.

Peart actually died Tuesday. It took four days for the information to reach the public, an eternity in today’s supercharged news cycle driven by social media. The fact that his inner circle, and band mates Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson, kept this secret was certainly in character.

Peart rarely consented to interviews, and was hardly ever in line for meet-and-greets. The man who wrote “Limelight” was famous for resisting its glare.

Peart was no ordinary artist. His fellow drummers will tell you that — the late heavy-metal drumming great Vinnie Paul used to recall how he nearly collapsed while mirroring such musical forays as “La Villa Strangiato,” the nine-minute instrumental from “Hemispheres” that was cut into nine sections.

Rush songs ran long, oh yes, especially over their first several albums. The opening suite on “2112” extends for more than 20 minutes, forever for a teenager. Talk show host Stephen Colbert, a famed Rush fan, once asked, “Have you ever written a song so epic, that by the end you of the song, you were being influenced by yourselves?”

Colbert also asked, as if speaking for all Rush fans, “You’ve been touring for 30 years, do you ever get tired of being so awesome and kicking so much ass?” The band could only laugh.

Maybe you recall the first time you heard your favorite band. Mine was when I was 15, and a friend played — on a Maxell metal cassette — Side 1 of “2112.” I’d never experienced anything like this sound shaking his 1969 Chevy Camaro, outfitted with a six-speaker, Blaupunkt car stereo. It was as if we were sitting inside a woofer.

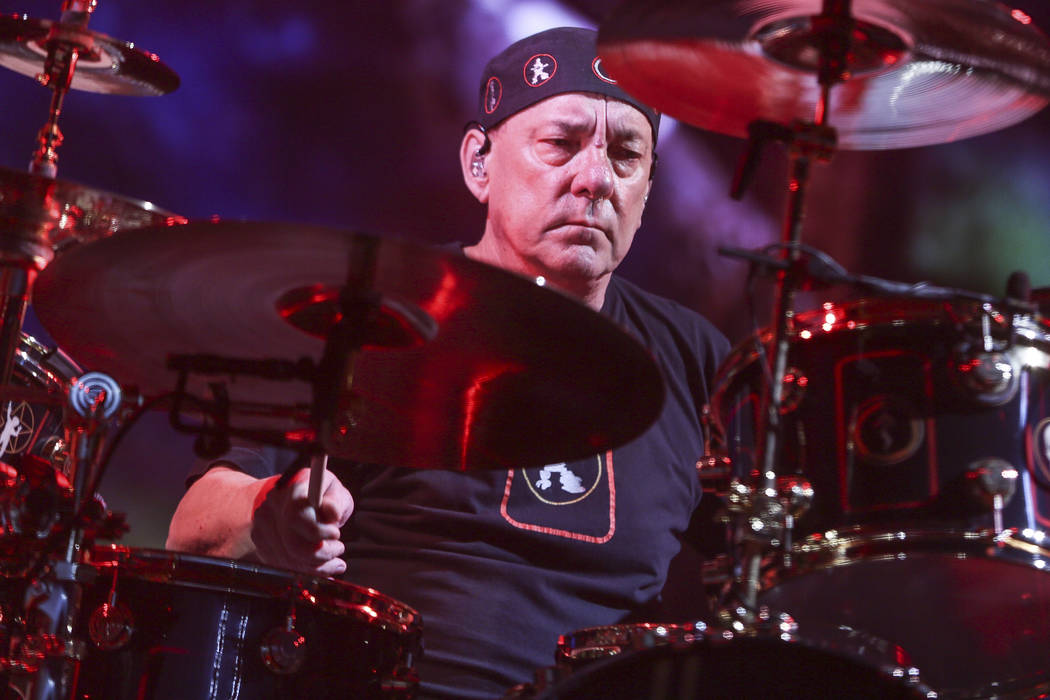

I saw the band at least a dozen times, first at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, when it seemed the big barn would collapse for Peart’s percussion. If it was possible to develop a visceral connection to a drum solo, it was that night. It is mind-blowing, even now, that three men could produce such power.

Peart was known, of course, for his otherworldly lyrics. He was an artist you could read outside the music, easily, as if producing a series of novellas with every release. The first album I’d actually read the lyrics to was the breakout “Moving Pictures,” marveling at how Peart’s storytelling matched the band’s progressive patterns.

On “Moving Pictures,” Peart wrote about a sports car, the mythic “Red Barchetta,” relating, “Well-weathered leather, hot metal and oil, the scented country air. Sunlight on chrome, the blur of the landscape, every nerve aware.”

This was a far cry from, say, the Beach Boys and fun-fun-fun until daddy took the T-Bird away.

Songs began, “When the ebbing tide retreats, along the rocky shoreline. It leaves a trail of tidal pools, in a short-lived galaxy.” Peart used forests as a metaphor for class conflict in “The Trees,” offering, “The maples want more sunlight, and the oaks ignore their pleas,” and ending with, “And the trees are all kept equal, by hatchet, axe, and saw.”

Even my friends who loved rock — and as youngsters we all roared to Led Zeppelin, Van Halen and AC/DC, too — rolled their eyes. What is this?

But we stopped trying to defend Rush a long time ago. We’re done explaining this band, which reached the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame but now exists in past tense, having lost its heartbeat. The master musician’s passing in private was actually a favor, allowing Rush to be remembered at peak proficiency. Whether it was at age 15, or in “2112,” Neil Peart was an artist for all time.

John Katsilometes’ column runs daily in the A section. His PodKats podcast can be found at reviewjournal.com/podcasts. Contact him at jkatsilometes@reviewjournal.com. Follow @johnnykats on Twitter, @JohnnyKats1 on Instagram.