African-American doctor’s upbringing pushes him to excel in three specialties

Sixty-three-year-old Dr. Carl Williams walks into North Vista Hospital carrying the first dollar he made more than 30 years ago as a hand surgeon.

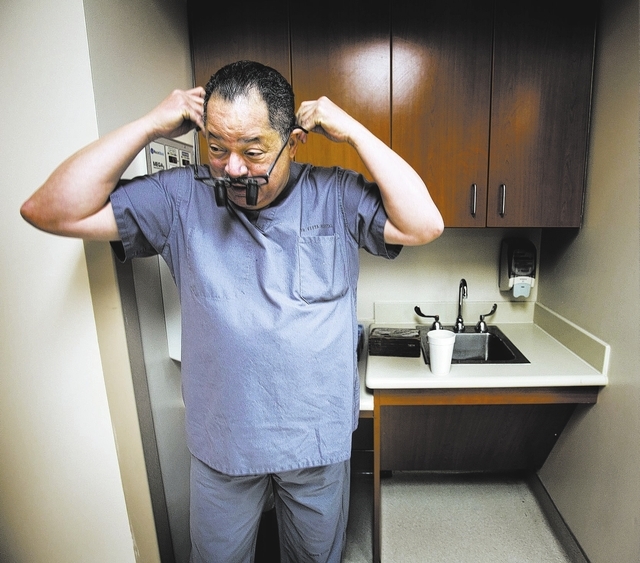

The worn, wood container originally held, and still holds, the African-American physician’s first pair of surgical magnification glasses — lenses he purchased decades ago for $200, equipment he continues to wear in operating rooms throughout the Las Vegas Valley.

The pen his mother gave him as he started his career in medicine sits alongside the dollar bill and glasses. Taped to the box are patient identification adhesive labels, the kind of computer-generated tags patients wear around their wrists in the hospital.

On this day, Williams, one of the few doctors board certified in three specialties — ear, nose and throat as well as plastic and hand surgery — will perform a cosmetic eyelid procedure on a middle-aged woman.

The box, as it always does, goes with him to the operating theater.

“For me, it’s like the security blanket Linus always carries in the ‘Peanuts’ comic strip, it makes me comfortable,” Williams says. “It also keeps me humble. That dollar bill is from the $200 cash I got for a thumb surgery. Those patient IDs signify cases that make me remember that no matter how experienced you are, there are often unforseen challenges you must overcome for a great outcome. You can take nothing for granted.”

As he goes to work during this Black History Month, he gently reminds people of African-American pioneers in medicine, including Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (no relation), credited with the world’s first successful open-heart surgery, a procedure carried out in Chicago in 1893.

“It’s good that people are reminded of African-American heritage,” Williams tells a surgical technician. “We can keep misconceptions from taking hold.”

What he doesn’t do, but what doctors who include Dr. Dale Carrison, chief of staff at University Medical Center, think should be done, is spotlight himself — Dr. Carl Williams, the first African-American hand and plastic surgeon in Las Vegas.

“Carl’s a great surgeon, a humble man, a caring man,” Carrison says. “When he’s on call at UMC for hand surgery emergencies, he never asks if the patient has insurance before coming in.”

Williams is of the school that good work speaks for itself. But the more you learn about Williams, the more you want to know. He may always carry a box to the surgical suite, but he’s a man who does a lot of his thinking, and living, outside the box.

Just the bare bones of his career sound like something that should be part of a black history highlight film.

After postgraduate training at Detroit’s Wayne State University during the 1970s, he became the first African-American trained there to treat problems of the eye, ear, nose and throat.

Later study at the University of Illinois in Chicago saw him become the first African-American trained at that school as a plastic surgeon, and for years he was the only black plastic surgeon in the Windy City.

With even more training, he became the first and only African-American hand and plastic surgeon in Chicago and the first black plastic surgeon in the United States to be board certified in three medical specialties.

“I really focused a lot on hand surgery because I realized that if people don’t have their hands they become a complete invalid,” he says. “They can’t even eat by themselves.”

What brought him to Las Vegas in the 1980s was the same thing that’s always brought most people to town — opportunity.

“I was told by people they really needed plastic and hand surgeons here,” he says as he sits in his office near downtown.

Although Sam Kaufman, the CEO of both Desert Springs and Valley hospitals, points out that Williams’ surgical skills have long been respected within the local medical community, it wasn’t until Maria Gomez nearly lost her hands during a savage machete attack by a former boyfriend in 2012 that most Las Vegans began to appreciate his brilliance in the operating room.

Dr. Jay Coates, a UMC trauma surgeon, described how Williams painstakingly worked for hours stabilizing fractures and reconnecting ligaments, tendons and nerves so the woman might use her hands again.

“The patience and sewing skill that takes is almost incomprehensible,” Coates said.

On two other occasions Williams operated on Gomez, whose hand injuries were suffered as she tried to protect her head from the machete. Her hands mended so well there was little doubt that Gomez, who called Williams “my angel” and sometimes would come by his office just to visit, would regain full use of both of them.

But just as it appeared that her life would get back on track, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer.

When she awakened after a procedure to remove a cancerous mass, one of her first visitors was Williams.

“Maria was such a nice woman who suffered far too much,” Williams says, his voice breaking. “She reminded me of my mother, who also was a victim of domestic abuse.”

A few weeks after her cancer operation, Gomez died from the disease.

Williams spoke at her funeral. He promised to open a foundation in her name dedicated to removing the physical scars of victims of domestic violence.

“She will not die in vain,” Williams vowed.

To this day, Rebeca Ferreira, head of Safe Faith United, an organization that aids victims of domestic violence, is amazed at how Williams reacted to a woman he had never met until he operated on her.

“How many doctors do you know that shut down their entire office and bring their staff to the funeral of a patient?” she says. “Maria Gomez wasn’t famous. She worked in a convenience store. She was a nobody to almost everybody but her family, but he respected her. How many doctors do you know who vow that no woman who has been abused in Southern Nevada will have to pay for plastic surgery?

“Maria was right. He really is an angel. He did a beautiful job on a woman who had her lip bit off by her boyfriend. Now she feels like she can go out in the world again.”

Williams, who has worked out a financial arrangement with a hospital that allows him to help abused women at no cost to them, closes his eyes as he remembers the woman whose lip was bit off.

“She told me the guy stood in front of her and made her watch him chew it up and swallow it,” he says. “I know this sounds strange but helping these women is helping me emotionally, too. I really couldn’t help my mother like I wanted to as a boy but now I’m able to do something. It’s helping give me closure over something that happened many years ago.”

How Williams says he got to this time and place in his life defines perseverance and sacrifice.

His mother, a college-trained social worker, worked to find help for those who couldn’t help themselves. For years, his father either sold cars or worked as a bus driver and butcher.

“My mother was exceptionally bright and talked my dad into going to college,” Williams says. “Her dad was a janitor and sent nine kids to college. With their studies and work, they got four or five hours of sleep a night. Education was really important to my mother. If I wasn’t studying five hours a day in high school and working part time, I was in trouble.”

Even though it took his dad, who came from a family of 10, more time to finish his higher education, Williams notes that education was considered important. Williams’ father and two uncles became doctors and another uncle became a dentist.

The medical and legal professions were often chosen by men in his extended family, he says, because they offered an opportunity for self-employment, where it became more difficult for a racist society to deny them economic stability because of the color of their skin.

Far too often, Williams says, both blacks and whites forget how important education has been in the black community. People often make the assumption, he says, that educated blacks are first generation and that athletics got them to college.

“When I was growing up, my Xbox was the encyclopedia,” recalls the surgeon who, like his dad, worked throughout his time in school. His first job was as a paperboy. “I just loved reading for hours as a boy, learning new things.”

When his dad became a doctor after attending the University of Indiana Medical School, Williams went with him on house calls.

“I knew right then I wanted to be a doctor,” he says. His uncle, Alex, also a doctor, delivered some children in Gary, Ind., who went on to become superstars in the entertainment world.

“Uncle Alex delivered both Michael and Janet Jackson,” Williams says with a chuckle.

Williams says that when his parents’ marital problems worsened he feared he wouldn’t get to become a doctor. Fearful that his mother would suffer injuries she couldn’t recover from, Williams talked his mother into leaving his dad — they divorced when he was 14 — and he and his two brothers moved with her to Chicago.

They lived in a small two-bedroom apartment largely on his mother’s earnings. His father, he says, “wasn’t very supportive … it’s behavior hurting many children today. Parents have to take care of their children even if they divorce.”

In a largely white high school, Williams, who contributed to family finances by working as a stocker at a pharmacy, found himself frequently called racial slurs. He had to suck it up and take it, he says, because he was one against many. The only black on the basketball team, he says he had to get used to taking more than his share of elbows in the face in practice from teammates and from opponents during games.

“I liked the classroom the best because there no one had an unfair advantage,” says Williams, always an honor student.

Unlike many members of his extended family who went on to study at largely black colleges, Williams went to the integrated University of Indiana, working in the steel mills in the summer and at odd jobs at school that included refereeing intramural sports to pay his way through.

“My mother said I wouldn’t be living in an all black country so I might as well go to an integrated school,” he says.

By the time he graduated from the University of Indiana Medical School — he and his dad became the first black father-son duo to graduate from that medical school — he and his father were able to talk again.

“I think he acted as he did because of how he was treated,” he says. “When he was in medical school, for instance, he could only have a black lab partner. He was angry about double standards. But that’s no excuse for how he treated my mother.”

After finishing postgraduate work in eye, ear, nose and throat in Detroit, Williams told professors he also wanted to study plastic surgery. “One told me, ‘Carl, why would you want to do that? Black people don’t get plastic surgery.’ I told him I wasn’t limiting my career to just black people.”

Even though he was a top student in plastic surgery in Chicago and ended up teaching students, there were several medical facilities that wouldn’t let him practice. When he heard about an opportunity in Las Vegas, he jumped at it.

But there were setbacks here, too. Despite his stellar credentials, one hospital wouldn’t give him privileges for two years. Because he takes patients to that hospital, he doesn’t single it out for criticism.

What eased his transition, he says, was a friendship he developed in the 1980s with Angie Wallin, then head of community relations for what was known as Community Hospital (now North Vista Hospital) in North Las Vegas.

Wallin, the executive director of Nevada Arts Advocates, says she was immediately impressed when Williams applied for privileges at North Vista.

“He was kind of a threat to existing physicians who didn’t have his qualifications or talent,” she recalls. “I put on seminars for the public that showed what he could do. People really responded.”

Racial tension cropped up in Williams’ life from time to time. Sandra Harvey, a nurse and administrator for Williams, remembers when a patient with a hand injury at UMC initially refused to have “that black man touch me” and said he’d wait for the best help. Harvey recalls Williams calmly telling the man he’d be waiting for a long time because he was the best hand surgeon in town.

“The patient changed his tune and his family was very appreciative for what Dr. Williams did,” she says.

Cyndi Leavitt, a Las Vegas animal control officer who was mauled by a dog in 2010, says the only reason she can use her hands today is because of the surgical skill of Williams. And she also says that the only reason she can continue to do her job “is because he helped me emotionally. He made sure I had someone to talk with. He wasn’t content to just help me physically. He recognized that I had post-traumatic stress syndrome and got me help for it.”

Williams, who has three children, two of whom are still in high school, says he would like his life to stand for the same thing to people of every race: “Hard work eventually pushes through to something good at the end of it.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.