Alzheimer’s studies urge active retirement

Dr. Jeffrey Cummings, one of the world's leading Alzheimer's disease researchers, sits in his Las Vegas office and says a laid-back retirement may literally cause people to lose their minds.

Quitting the world of meaningful work for a retired life of lounging around with a TV remote may seem enticing, but the physician-scientist has a word of caution: That passive lifestyle is increasingly seen by researchers as a high risk factor for Alzheimer's, a still incurable disease of the brain that causes the progressive degeneration of brain cells.

It is shortly after noon Monday and a scheduled meet-and-greet -- Cummings recently took over leadership of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health near downtown Las Vegas -- has quickly veered from pleasantries about family to a discussion about keeping Alzheimer's at bay.

Make no mistake: The 62-year-old Cummings is all about finding a way to knock out a disease that is expected to affect close to 16 million Americans by 2050, about double today's number.

The highly respected Journal of Alzheimer's Disease ranks Cummings as the sixth most prolific researcher of the wretched condition that robs people of memory, noting that his hundreds of papers are regularly cited by other scientists.

Fully expecting the Ruvo Center to be a major player in the national debate on how to deal with a health care crisis that worsens daily as 77 million baby boomers head into retirement, Cummings said it is time -- actually well past time -- for the nation's top governmental leaders and public health officials to have a frank discussion about the implications of retirement and a disease where age is unquestionably a risk factor.

"We have a social idea of what retirement consists of and we need to re-examine that idea," Cummings said. "The logical extension of the data we have on dementia is that a person who is still capable of working, who is mentally stimulated with a strong sense of purpose, is better off from the cognitive point of view continuing to engage in that position."

In other words, retirement may well be bad for your mental health.

It is an observation, though grounded in scientific studies, that Cummings said is seldom discussed in public by members of the American medical community.

To even suggest such a thing "flies in the face of a cultural norm," he said.

Yet Cummings said it is a discussion that must be had. And not just because of the very human desire to keep people from wrecked lives, from grieving the loss of a person who is there only in body.

It also is a question of dollars and cents.

If present trends continue, Alzheimer's will cost taxpayer-supported Medicare and Medicaid $20 trillion between 2010 and 2050, according to an Alzheimer's Study Group report released last year.

In calling for a public-private effort to garner more research money to first delay the onset of the disease and then to prevent it, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, co-chairman of the study group, said finding a way to delay onset of the disease by even five years could save the nation $8.51 trillion over the same 40-year time frame.

"It seems to me that the question of retirement and Alzheimer's has to be an important part of the dialogue into slowing down the onset of the disease," Cummings said.

A British study published last year in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry concluded that working beyond the normal retirement age of 65 appeared to keep dementia at bay.

Analyzing medical records of 382 adult male dementia patients, researchers found that, all other factors being equal, Alzheimer's symptoms were delayed about seven weeks for each extra year the men worked.

While researchers only looked at men, the study's authors said they believed similar findings would probably apply to women.

"Use it or lose it; that's the message from the data," said the study's co-author, Dr. John Powell. "The thing to avoid is giving up work early and becoming a couch potato."

Cummings said some researchers believe a trait called cognitive reserve can help explain why certain people are able to stay mentally sharper longer than others. The term applies to the brain's ability to cope with damage, such as the plaque that clogs the brain in Alzheimer's, while still functioning normally.

A life full of mentally challenging activities, such as pursuing an education, working at a stimulating job and meaningful volunteering, may contribute to building cognitive reserve, researchers say.

That cognitive reserve could still be modified late in life through work, according to the British researchers, showed the positive effect of cognitive activities later in life.

Cummings said studies have long found that intellectual stimulation and a sense of purpose can prevent a decline in mental abilities. He pointed to a 2009 French study of more than 5,000 people over age 65 which found that even engaging in activities such as practicing an artistic activity or playing cards just twice a week resulted in a risk reduction of 50 percent for all dementias.

And a 2010 study of seniors in Chicago showed that those involved in activities that gave them a strong sense of purpose were 2.4 times more likely to remain free of Alzheimer's than those with little sense of purpose.

Findings from the ongoing Religious Orders Study in Chicago, which includes the participation of more than 1,000 older religious clergy, have continually found that the "use it or lose it" exhortation is correct in relation to Alzheimer's.

Cummings said there is no question that there have to be more investigations into cognitive training in later life to conclusively prove its worth.

Given the American entrepreneurial bent, the lack of such conclusive studies has predictably produced a booming $100 million a year brain exercise industry. While the computer-based games may be inspired by science, Cummings said there is no scientific proof that they work.

A 2009 study published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, which reviewed all the existing trials on such products, concluded that none showed evidence of delaying or slowing the decline of cognitive skills, such as memory.

It is in the world of work, Cummings noted, where most people use their brain, find intellectual stimulation and a sense of purpose.

Yet even when people are highly productive workers later in life, he said, there is the expectation in the United States of retirement when they hit their mid-60s.

"People grow up with that; it is the norm," he said. "But for many people retirement is not what they should be doing. I would think our government might want to address that in some way."

Cummings pointed to acclaimed artists Picasso and Titian, who did some of their most creative and productive work in their 80s.

The world would have lost so much beauty if each man had decided to hang up his paint brush, Cummings said.

"There are many highly skilled older workers in jobs that shouldn't leave their jobs just because it is the thing to do," he said.

It isn't difficult to find Las Vegans who agree that the mid-60s are too early to retire.

Dr. Dale Carrison, the 70-year-old head of University Medical Center's emergency services, still regularly works 12- to 14-hour days. Not only is he seeing patients, he also is the hospital's chief of staff, chairs the state's Homeland Security Commission, works as a SWAT team physician and is head of emergency medicine at Las Vegas Motor Speedway.

"I love the intellectual stimulation," Carrison said. "I think I would deteriorate rapidly if I wasn't in an environment where I had a chance to make things better. I want to be around people who are always wanting to learn new things. And that has nothing to do with chronological age.

"I don't want to be around people who've stopped learning, who've stopped making a contribution. Unfortunately, we have young and old people who are like that, who don't live a meaningful life."

Former U.S. Maj. Gen. Scott Smith, the 75-year-old director of University of Nevada Las Vegas Institute for Security Studies, starts his workday at 6:30 a.m. and seldom leaves until 12 hours later.

Smith heads a staff who is devising practical and cost-effective solutions to security and terrorism related challenges, often training first responders and emergency management personnel.

"I cannot conceive of vegetating," Smith said. "I watched several of my friends die in retirement that way. ... I've always believed that you earn your daily bread. ... There are so many needs in our communities today where someone who is retired can really help -- the homeless, the disadvantaged, veterans' communities. To sit back in retirement and say, 'Thanks a lot; I've got mine,' and basically do nothing is not why we're here on Earth."

Cummings stressed that not all people who remain mentally active through work are protected against Ålzheimer's.

"Some people will still get the disease," he said.

Genetics and lifestyle choices basically determine how far down the forgetful road we go, he said. And those choices can be every bit as dynamic a positive force as genetics can be a negative one.

"We have learned that the more active people are in their later years, the less likely they are to be cognitively impaired," he said.

While studies may indicate that working beyond normal retirement age helps ward off Alzheimer's, Cummings said they shouldn't necessarily be interpreted as a prescription for people to work years longer to avoid the disease.

Cummings said staying past retirement at a job that is stressful and not fulfilling wouldn't make sense. Risk of dementia increases when people are stressed out, which often leads to severe hypertension, another potent risk factor.

What Cummings definitely would like to see, at the very least, is people actively engaged in something meaningful in their retirement.

"Meaningful volunteerism where people really worked to make a difference, where they have a sense of accomplishment and purpose, would be both good for the nation and for mental health," he said.

But he said it is very possible that many people need the external discipline that a job brings to be actively engaged in mentally challenging activities.

"Perhaps people wouldn't work a full 40 hours and the government could work with employers to make that transition," he said.

"Retirement and Alzheimer's" -- the way Cummings hesitates before moving on with his thought makes it appear he may be sounding out a title to yet another study -- "How those two fit together should be part of the national dialogue. How we deal with this issue could change the way we think about occupations and aging."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

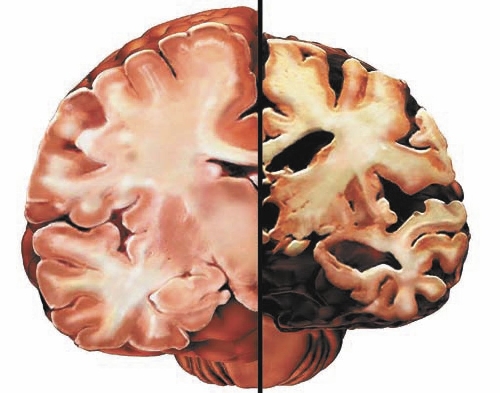

BRAIN CHANGES

In the Alzheimer's brain, the cortex shrivels up, damaging areas involved in thinking, planning and remembering. Shrinkage is especially severe in the hippocampus, an area of the cortex that plays a key role in formation of new memories. Fluid-filled spaces, or ventricles, become larger.

Source: Alzheimer's Association