Deep brain stimulation surgery helps some Parkinson’s patients

Two years ago, Kip Smith frequently couldn’t sleep more than 30 minutes a night. No matter what he did, he couldn’t keep his legs from trembling or escape the spasms that jerked him awake.

His days were often filled with other frustrations. The right-handed Smith’s right shoulder became so frozen in place that he could no longer write or eat with his right hand. Muscles in his right leg would stiffen so much that walking only 100 feet caused such cramping in his right foot that he’d have to stop to take a break.

The medications the meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration took to control the tremors and rigidity of Parkinson’s disease made his skin itch. And the dizziness that had been an infrequent side effect of the drugs was occurring with more regularity.

“I didn’t want to go on disability,” Smith said recently as he sat in his Mountain’s Edge home in southwestern Las Vegas. “But I knew that I’d have to unless something changed drastically.”

That something changed drastically for Smith is obvious in his ability to work out at home on an exercise machine without any trace of rigidity. His right shoulder no longer prevents him from writing or cutting a baked potato or steak right-handed.

He now can take long walks to stay in shape. The tremors that made it nearly impossible to work a computer are no longer evident. His legs relax at night so he can sleep. He’s no longer on medications. Work is no longer a struggle.

The only hint that something is off with Smith is his speech, which is a tad slow.

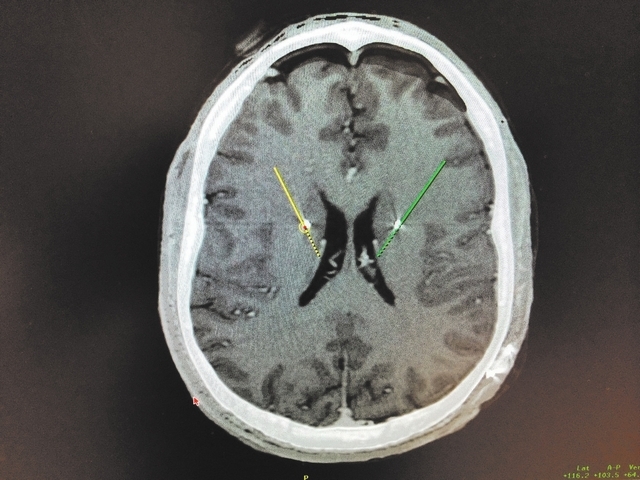

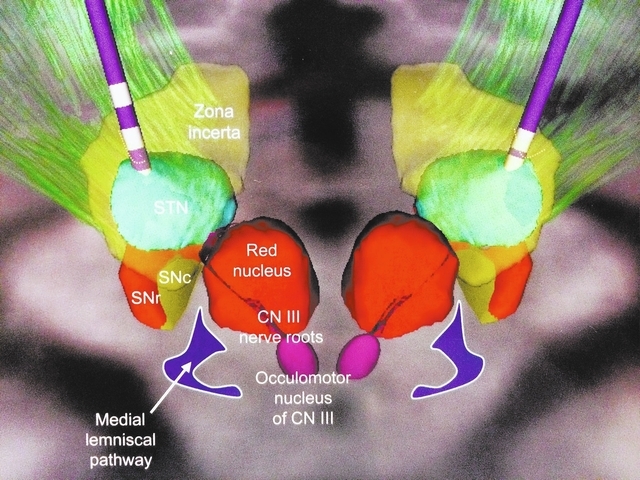

Deep brain stimulation surgery in 2012 transformed Smith’s life. Neurosurgeon James Forage performed the surgery at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, implanting electrodes deep in Smith’s gray matter, or subthalamic nucleus, that jam dysfunctional signaling in his brain.

Smith, who is 58, has started a support group for those who have had or are considering having deep brain stimulation surgery. He has come forward now to suggest that those in early stage Parkinson’s consider the surgery.

It is a controversial position. Most neurologists don’t recommend the surgery, which carries risks, until several years after a patient has been diagnosed, after medications have lost all effectiveness.

“The traditional waiting means patients are generally in bad shape by the time they have it,” Smith said. “I wasn’t doing well and I had just been diagnosed two years after I had the surgery. Some people have to wait far longer than I did. If I had waited much longer, I wouldn’t have been able to keep working.”

The surgery, approved 13 years ago by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for Parkinson’s, is not a cure. As the disease progresses, doctors regulate, without further surgery, the rate of electrical impulses to the target areas of the brain, which block the impulses that cause tremors.

How many years symptoms can be controlled, however, is unknown because the surgery is still relatively new. To date, patients who’ve had the procedure still receive benefit from it.

Smith’s wife, Kitty, is amazed by the difference the surgery has made in her husband.

“There are few things that are true medical miracles,” she said, “but this is one of them.”

Smith said his colleagues saw a difference in him as soon as he returned to work.

“I smiled as I walked down the hallway and people said they had never seen me smile before,” Smith said, explaining that Parkinson’s leaves many patients with a “masklike” face that shows little expression.

Dr. Bess Chang, a neurologist, recommended Smith consider the surgery not long after she diagnosed his tremors as Parkinson’s in 2010. She believes waiting for the surgical therapy can needlessly affect quality of life and cause people to be placed on disability when they could still be productive.

“My thoughts are, why make someone miserable for 10 years when in the end they will have to have DBS anyway,” she said. “Mr. Smith was a young guy who wanted to work, who was already building up a tolerance to medications. We need to consider in young patients to preserve quality of life.”

Dr. Eric Farbman, a neurologist at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, said he’s not against deep brain stimulation surgery but is cautious in recommending it to patients early in the progression of Parkinson’s. He sometimes attends meetings of Smith’s support group to answer questions about the surgery.

“If I can give someone relief with three pills, is it worth the risk of doing brain surgery?” he said. “We don’t know what other therapies are going to come out in the next two years.”

Parkinson’s afflicts about 1 million people in the United States. Farbman said about 22,000 people have the disease in Clark County. Symptoms occur for most people after age 50.

Why the disease named after Dr. James Parkinson develops remains unknown, though some experts believe the disease is inherited. In 1817, Parkinson labeled the disease he found in several patients “shaking palsy.”

Parkinson’s, a central nervous system disorder, keeps an individual from totally controlling body movements.

In people with the disease, basal ganglia nerve cells deep in the brain, which make and use dopamine, a brain chemical helping to control movement, are damaged. Because dopamine levels are low in someone with Parkinson’s, the body doesn’t get the messages it needs to move normally.

Medications for Parkinson’s try to correct the shortage of dopamine.

As soon as early medications begin to lose effectiveness in lessening the disease’s symptoms, Chang said it’s time to consider deep brain stimulation surgery. She says it’s important to consider this before cognitive decline sets in and the “window of opportunity” for having the surgery closes.

Prescribing one drug after another to try controlling the progressive disease’s symptoms may close the window, she said. She never wants a patient on more than three or four medications.

Farbman had a patient come to him five years ago who was on 22 medications.

That patient, Ken Perrigo, a former chief financial officer of an auto loan company, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at age 39. Perrigo was unhappy with his former neurologist, who kept prescribing more medications that seemed to make him worse rather than better; he could only get around his house safely by crawling. On disability, Perrigo used a wheelchair to get around outside his home.

All the medications Perrigo took gave him the same erratic, spastic movements that people often associate with the actor Michael J. Fox, who also has Parkinson’s.

(Years ago, Fox had a different kind of brain surgery that didn’t alleviate all of his symptoms, and he has said he won’t have any more surgery unless it’s a cure.)

Perrigo told Farbman that his prior doctors hadn’t mentioned deep brain stimulation surgery in the 12 years he had seen them.

Perrigo’s disease had progressed, but he still hadn’t suffered cognitive decline. So Farbman recommended the surgery for the 51-year-old patient. The 2008 procedure allowed Perrigo to play golf and bowl again. He is still doing well today.

Farbman said Perrigo should have been offered the procedure long before he was.

It is possible, Farbman said, that a Vanderbilt University study may lead to deep brain stimulation surgery being recommended to new Parkinson’s patients soon after they’re diagnosed. The study may confirm what several researchers have hypothesized — that if the surgical therapy is applied very early, it might modify the disease’s progression.

“There is tremendous interest in that study by doctors and patients,” he said.

When given later in the disease’s progression, as it most often is now, the surgery gives an average of five additional hours of good movement control each day compared with medication alone.

Smith’s outcome, neurologist Chang said, is as good as it gets.

Smith didn’t immediately agree to the surgery. He read everything he could find on deep brain stimulation surgery, talked to others who had it. Less than two years after she suggested the surgery, Smith agreed; he decided the benefits outweighed the risks.

“At some point,” he said, “you have to trust the people who are trained to do this, that they know what they’re doing and can do it right.”

The idea of someone drilling holes in your head, Chang said, would give anyone pause. Although the risk of death from the procedure is less than 1 percent, there are also the dangers of strokes, bleeding inside the brain, seizures, infection and impaired speech.

A Veterans Affairs study of 255 Parkinson’s patients that took place between May 2002 and October 2005 found that the overall risk of experiencing a serious adverse event was 3.8 times higher in deep brain stimulation patients than in patients who just took medicine.

Of the more than 50 patients of hers who have had the surgery, Chang said only one had complications. A patient in her 80s, who really wanted the procedure but had some indication of dementia, kept picking on her stitches after the operation and her scalp became infected.

Later, the area inside her brain became infected, too, and the implant was removed.

Antibiotics, Chang said, addressed the infection, but DBS was not tried again because of the woman’s cognitive problems.

From that case, Chang said she learned that age and cognitive impairment must be heavily considered in recommending the surgery.

Chang said the rest of her patients who have had deep brain stimulation surgery “have no regrets” after undergoing the procedure.

Of 90 Farbman patients who had the surgery, one had complications. That patient suffered a small stroke but the surgery still has helped him, the neurologist said.

After Smith told Chang he wanted the surgery in 2012, she contacted neurosurgeon Forage, who has been doing the procedure for about 10 years.

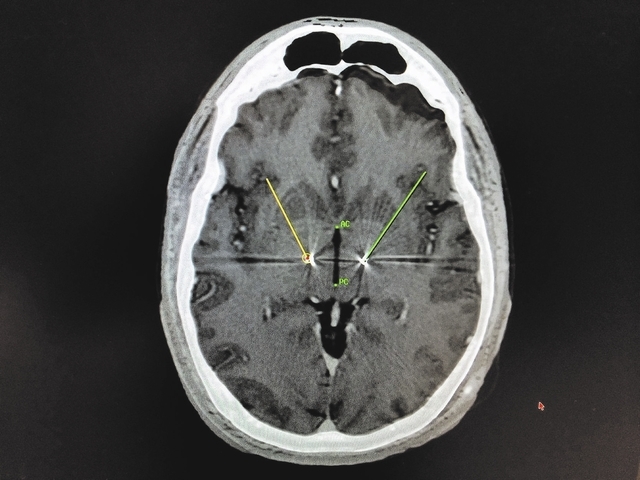

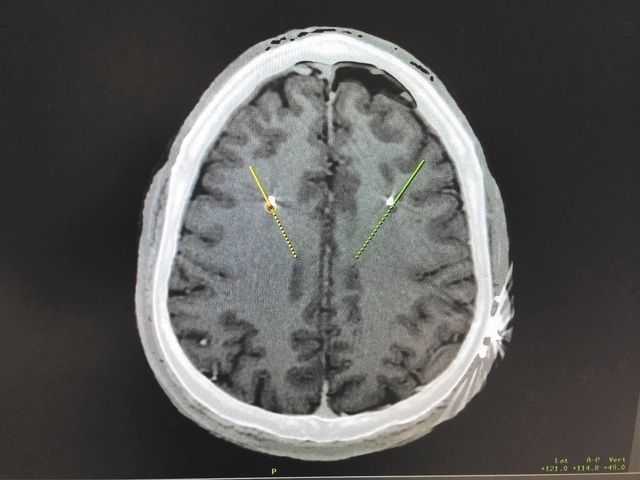

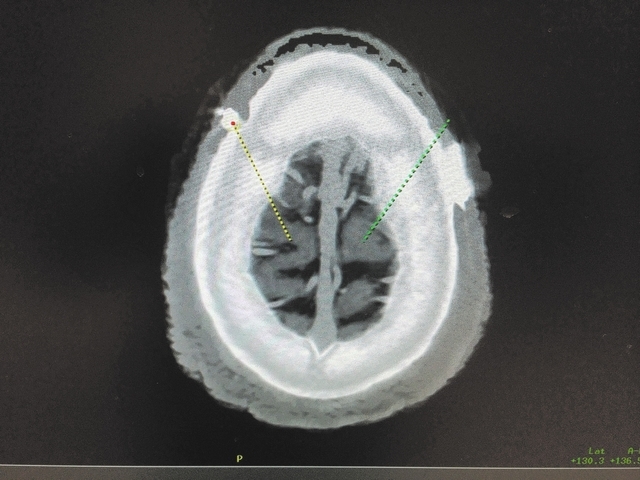

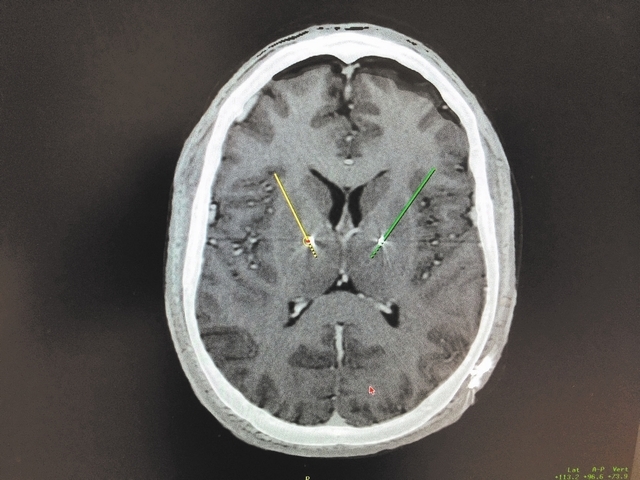

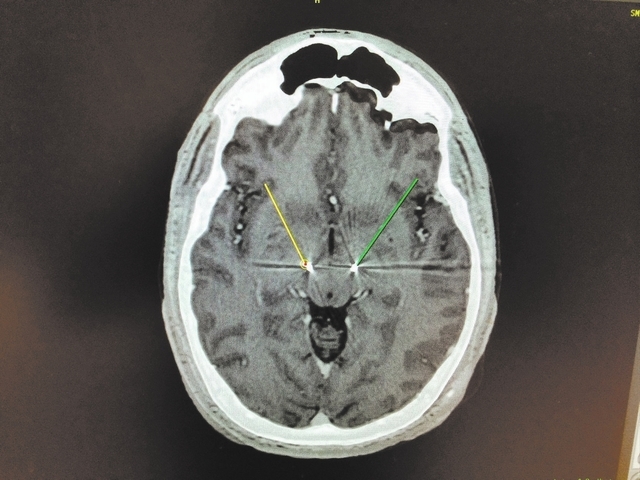

Forage stood inside a Sunrise Hospital operating room and displayed images of Smith’s brain. The surgeon explained how, on the first day of the two-day operation, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging allowed him to precisely find the targets to place the electrodes.

“It is a great treatment and, I believe, underutilized,” he said. “There’s a pretty sizable population that could benefit from it. Some people are just afraid, and that’s understandable. It is brain surgery.

“I have had surgeries before and I’m nervous. For the average layperson, it’s the most terrifying and frightening thing they’ll ever have done. But the difference in quality of life is amazing.”

Before the surgery can happen, the patient is taken off Parkinson’s medications.

Smith’s wife, Kitty, couldn’t believe how serious her husband’s symptoms had become.

“He was really shaking,” she said.

On the day Forage was to implant the electrodes, Smith’s head was held in a frame that amounts to a sophisticated vise. Smith felt no pain as the surgeon worked inside his brain; anesthesia allowed Smith to answer questions from Forage about sensations he was feeling.

“It is critical that we implant the electrodes in just the right places,” Forage said.

After the electrodes were implanted in Smith’s subthalamic nucleus, Forage connected them to a type of pacemaker device that he implanted under the skin of Smith’s chest.

Smith was given about a month to heal before the device, developed by Medtronic, was activated.

Though Chang programs the device, Smith can partially regulate it himself. By turning the voltage in one direction, his speech is less impaired but he then may have slight tremors.

Smith’s wife said the surgery largely gave her back the husband she knew before Parkinson’s.

“Just the controlling of tremors is a blessing beyond compare,” Kitty Smith said. “I don’t know where we would be right now if he hadn’t had the surgery.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.