Genetics company looking at what can make athletes better

In an old ad campaign, Gatorade asked athletes, "Is it in you?"

A Canadian company doing work in Las Vegas wants to help athletes answer another question: "What is in you?"

Jeremy Koenig, CEO of Athletigen, based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, visited the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine at UNLV in October to talk about how genetic testing can help athletes become better, stronger and faster by leveraging the genes within them.

"We must look at bodies as systems," Koenig said. "A lot of insight can be offered to individuals based on what we've learned about genetics thus far, but it's also an opportunity to greatly accelerate research."

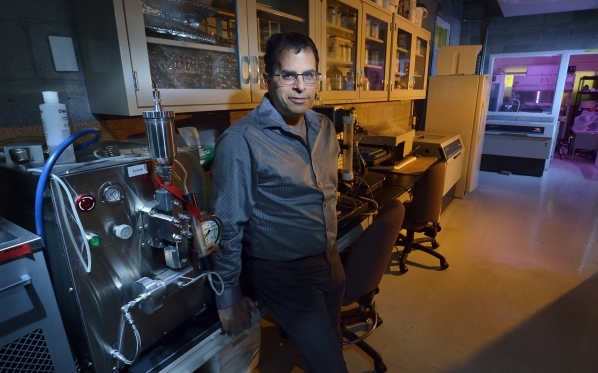

Martin Schiller, executive director of the institute, is adding Koenig's company to his collaborators and partners such as the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Brain Center for Health, SWITCH Communications, Intel and several members of the UNLV community, including the National Supercomputing Center, School of Nursing and the planned School of Medicine.

The institute is conducting research, developing technology and providing education and training to improve individual and community health in Nevada. Personalized, or precision, medicine looks at genetic makeup to help provide a blueprint for effective treatments and disease prevention strategies.

Koenig, who competed as a sprinter at the collegiate level in Canada, started Athletigen to help athletes use their genetic code to boost performance.

"I've always looked at microbiology and science through an athlete's lens," he said.

Mapping genetic route

The complete mapping of all the genes of human beings by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium was completed in 2003. Since then, scientists have studied the data for ways to give health care providers new powers to treat, prevent and cure disease.

Genes, the physical and functional units of heredity, contain instructions that control cellular reproduction and function. The Human Genome Project estimated that humans have between 20,000 and 25,000 genes.

All people inherit a copy of each gene from their parents. Most of a person's genes are the same, but some are slightly different. Those gene variants contribute to each individual's unique physical features.

As more genome sequences become available, geneticists draw a better understanding of variations driven by gene transmissions between cells that not only generate new assortments, but move genes throughout populations and from species to species. Understanding how bacteria share genes, for example, could help infectious disease experts thwart antibiotic resistance, when bacteria adapt making medications less effective.

The contributions genetics has made to evolutionary biology has led many scientists to see not an evolving tree of life, but more of a forest of life.

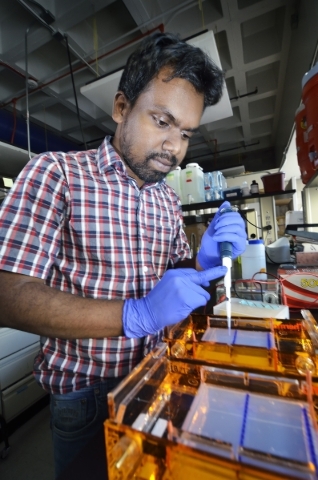

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing has become more affordable, and tests are sold over the Internet, through TV advertising or other marketing venues without involving health care professionals. Microarray analysis is more targeted, employing computerized, robotic technology to find mutated or missing genes and quantify the amount of a specific DNA fragment.

"Over the years with advances in technology, whole genome sequencing costs thousands of dollars instead of billions of dollars, and with microarray technology, only hundreds of dollars," Koenig said.

Athletigen incorporated in April 2014 and applies data about gene variants to athletic performance. The company offers athletes another tool to accomplish their goals.

"There are different ways to succeed," he said. "Just because you have a particular variant doesn't mean your're predestined to being a sprinter."

Accelerating research

Athletes mainly focus on training, conditioning, nutrition and coaching to provide them most of the tools they need to succeed. The higher the level of competition, the more athletes are looking for an advantage.

Knowing their genetic makeup gives them a tool that will not raise questions about whether they are seeking an unsanctioned performance enhancement.

Genetics can help show athletes whether they have a tendency toward endurance or power and their maximum level of oxygen consumption.

When athletes know their risk for injury, for example, they can take preventative measures by adjusting their training routines and taking steps to ensure their rest and recovery after exertion.

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are the most common knee injuries among athletes. Known as a torn ACL, the injury is immediately disabling, requires a long-term recovery process and has other consequences, such as a risk for osteoarthritis.

Researchers have shown that a gene important in collagen production, COL1A1, can affect an athlete's risk for an ACL injury. Collagen is the key protein found in connective tissues such a ligaments and tendons. Research has shown that athletes with subtle gene variants are more likely to have suffered an ACL injury than those without the variants.

Collaboration between private industry and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas precision medicine initiative offers opportunities for new discoveries, Koenig said.

"A lot of insight can be offered to individuals based on what we've learned about genetics thus far, but it's also an opportunity to greatly accelerate research," he said.

Doctors embracing genetics

Schiller's organization began in 2013 as the Institute for Quantitative Health Sciences, funded by a $2.5 million grant through the Governor's Office of Economic Development. The money was part of $10 million budgeted that year to spur research, innovation and commercialization in Nevada.

The name was changed to the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine to align with the movement in health care to deliver the right treatments, at the right time, every time to the right person.

For example, Schiller's group is categorizing Alzheimer's disease patients in cooperation with the supercomputing and Ruvo centers. The intent is to determine the best course of treatment for patients based on what type of Alzheimer's they have, a process in which genetics can play a key role.

The institute will be part of the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence, which in September was awarded an $11.1 million federal grant to advance the understanding of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases.

"Everything can be optimized based on one's genetics, but you have to separate the variants first," Schiller said. "You have to know who's in what group."

Schiller said precision medicine soon will be a routine part of the standard of care in medicine to predict a person's risk for disease, examine options for treatments and refine drug dosages to improve outcomes.

One family practitioner in Las Vegas, Dr. Robb Rowley, already has incorporated genetics into his practice. Rowley, who worked in the office of the U.S. Air Force surgeon general as the chief of medical bioinformatics and genomics before moving to Las Vegas in 2005, has the complete gene sequencing of four of his patients.

That data helped him diagnose one of them with a condition that previously had stumped medical professionals.

"The challenge will be what to do with the data and who has a better interpretation," Rowley said. "The most promise is in how we can use your genes to predict your risk for disease and how you're going to respond to treatment if you get sick."

The field of medical genetics is limited by the lack of specialists. Las Vegas pediatrician Dr. Colleen Morris is one of only three fellows of the American College of Medical Genetics in Nevada.

Morris has witnessed a revolution in medical genetics since graduating from medical school in the 1980s, and she said the improved outcomes achieved since the mapping of the human genome are growing exponentially.

Genetic testing can help identify patients with autistic spectrum disorder, Morris said, and help other patients who have lived for years with what clinicians call the diagnostic odyssey. Patients can live for years with symptoms and never know why.

"The process can be long and frustrating for patients and families," she said. "Finding the underlying genetic cause can make sense of a patient's symptoms and point them toward the best course of treatment."

Over the next two years, Schiller will work with the faculty of the planned UNLV School of Medicine to incorporate genetics into the curriculum for the first students who would be starting class in September 2017. Schiller said those doctors-in-training will benefit from their association with the institute and will be more apt to consider genetics as a specialty.

"These doctors are unique. They're a special breed," Schiller said. "They're doctors who think like scientists."

Contact Steven Moore at smoore@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow him on Twitter at @steve_smoore_rj