Half a heart, full life: Teen stands as walking miracle

As a grinning 18-year-old Zachary MacKenzie walked across The Orleans stage recently to receive his diploma during Bonanza High School’s graduation, his proud mother remembered how she sobbed when she learned he’d go through life with half a heart — if he survived childbirth.

And she recalled that for six months her pregnancy with Zach was as normal as those she had for his two older sisters.

“I had so many thoughts going through my mind at once seeing him graduate,” said Tracey Moran, a behavioral health specialist and cosmetologist. “I was 23 when everything changed, when nothing seemed simple anymore, when all there were, it seemed, were sleepless nights. I was just so scared I don’t think I slept for years.”

How Zachary MacKenzie has not only survived but flourished despite being born with a congenital heart defect that killed most children then is a testimony to modern medicine — and to his parents having the good luck to have access to the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, a site where risky surgeries to rebuild newborns’ tiny, walnut-size hearts were carried out.

It also helped that his parents rejected the first option the obstetrician gave them for dealing with the birth defect that showed up on an ultrasound in the sixth month of pregnancy — abortion.

“When the doctor said that, the decision by my husband and I was mutual and immediate,” said Moran, who has since divorced Mark MacKenzie and remarried. “We looked at the doctor and both told him to do everything possible to save the baby. We had faith in God that our child could thrive.”

Zachary MacKenzie nodded as he listened to his mother in the living room of their northwest Las Vegas apartment.

“I’m obviously glad my mom and dad did what they did,” he said, “but no one could really blame them if they had ended the pregnancy. The doctor knew that most of these cases didn’t end well.”

By the sixth month of her pregnancy, his mother clearly felt the life inside of her. She’d smile and caress her stomach when her baby moved at the sound of a car horn, when she listened to music.

Having read baby book after baby book about the stages of growth in fetal development, she had known that in the sixth month of pregnancy her baby’s arms, hands, fingers, feet and toes were fully formed, that her little one could even suck thumbs, yawn, stretch and make faces.

She remembered how she laughed when she saw, in her mind’s eye, the baby in her tummy making faces at her because of something she ate, how she didn’t give a second thought to the ultrasound her obstetrician had scheduled.

It was, after all, just part of the pregnancy routine.

What the ultrasound showed about Tracey and Mark MacKenzie’s unborn child was anything but routine — the fetus had a rare congenital defect called hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

“I was deployed with the Navy in Spain then,” said Mark MacKenzie, who traveled to Las Vegas from his Georgia home to see his son graduate. “My wife called me and I got back to the East Coast where she was within 48 hours.”

For some unknown reason, the left side of the baby’s heart did not develop properly in utero. The most critical defect of the condition stems from an underdeveloped left ventricle. Normally, the chamber is powerful, pumping blood throughout the body. But when it’s not developed, the body does not get the blood flow it needs to survive.

When the MacKenzies ruled out an abortion, their obstetrician gave them three other options. They could provide palliative and comfort care to the newborn at home, and the baby would probably die within one week. They could hope for a heart transplant, but it’s extremely rare to find a donor heart for a newborn.

Or they could allow the child to go through three complex surgeries in three years for a chance at life, if the child was born alive.

Even with surgery, the obstetrician didn’t think the child could live past age 10.

The MacKenzies decided to hope for a transplant but also wanted the surgical option should a heart be unavailable.

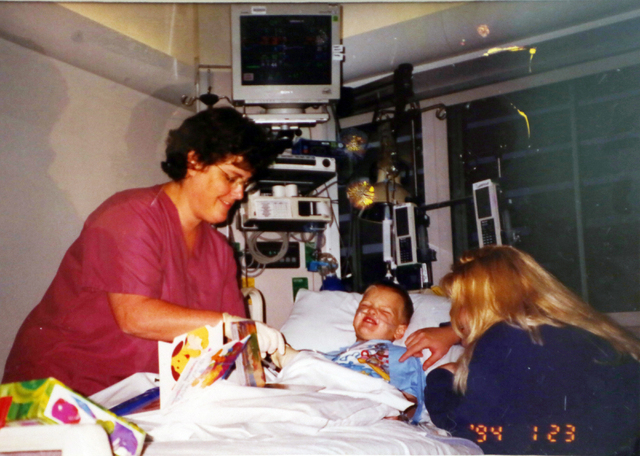

No donor heart became available and three hours after Zach’s birth surgeons began an eight-hour procedure, the first of three reconstructive operations he had by the time he was 3 years old.

By the time they were finished, the right side of the heart was doing what is usually the job of the left side — pumping oxygenated blood to the body. And the deoxygenated blood flowed from the veins to the lungs without passing through the heart.

”Sometimes it felt like we spent more time at the hospital than at home,” Mark MacKenzie said. “The Navy let me stay in Pittsburgh for three years.”

Dr. Frederick Leong, a pediatric cardiologist who had cared for Zach when the MacKenzie family lived in California, said Zach was fortunate to have a father in the Navy who could get insurance coverage for his son at one of the nation’s best hospitals.

The doctor can remember that it wasn’t that many years ago when Zach’s condition was generally considered a death sentence. Today, survival at age 5 years following all three surgeries is 70 percent to 75 percent.

“The surgery done on him back then was fantastic,” he said. “And his parents fought for him all the way. It also helps that Zach has a good attitude. He has to take medications for his heart for the rest of his life, including blood pressure medicine and he can’t really do endurance or contact sports, but other than that, he can do about anything. And he tries to.”

Bonanza High School administrators and teachers were stunned that Zachary did so well after moving to Las Vegas from California for his senior year.

“Generally, that’s very difficult for a student,” said Roger West, an assistant principal at Bonanza. “But he fit right in. He came in and just did a good job, got along with everybody. You had no idea that he has a medical issue. He worked in the front office and everyone liked him.”

Robert Kalinowski, Zach’s U.S. government teacher, appreciated his willingness to ask questions.

“He was very involved, interested, kept the classes going,” he said.

The teacher was impressed with the way he helped student council members prepare for assemblies and other events.

“He’d stay after school to be with them — he really seemed to like being with a group,” Kalinowski said.

Zach said Kalinowski’s observation is correct.

“I just liked the way they worked together,” he said. “If I had been here longer, I would have run for student council.”

If he hadn’t had to miss school so much for medical tests and treatments when he was young, Zach is sure his grade point would have been better than a 2.5 or a C plus.

“Sometimes you just can’t make up for lost time,” he said.

Zach has had few medical problems while in school.

“One time in California my heart started racing for no reason and I had to go to the hospital by ambulance,” he recalled. “They never could figure out what the problem was.”

He now has part-time jobs at Del Taco and Target, saving money for a car and to attend the College of Southern Nevada.

“I think I’d like to do something in the criminal justice field,” he said.

His mother said the only problem her son has now is to occasionally be unhappy about things he can’t do.

“Zach sees his younger brother Ryan running cross country and wrestling and he won’t say anything, but you can tell it just eats him up that he can’t do that,” she said, predicting that with more maturity he’ll stayed focused on what he can do.

Tracey Moran will never stop accentuating the positive about Zachary.

“I’m just amazed that the boy I was told had little chance at life has graduated from high school, attended the senior prom, works, and now talks about attending college and giving me grandchildren one day. He’s proof that miracles do happen.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.